![]()

1. Disruptive Shock Waves and

Dual Transformation

The year is 1975.

The Boston Red Sox lose in the World Series in heartbreaking fashion, again. The disco era begins, with the Bee Gees’ “Jive Talkin’” and Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Shining Star” topping global charts. In the town of Rochester, New York, a young engineer named Steve Sasson creates a disruptive technology that allows a consumer to capture what we now call a digital image. The device is as big as a toaster and takes more than twenty seconds to capture an image, but the seeds of disruption are sown. Far from working for an upstart company, Sasson works for Eastman Kodak. At the time the company dominates the silver halide chemical film market, with an 80 percent share and a 70 percent gross profit margin. And now it has a prototype for a camera that uses no film.

What happens next?

You probably know the story. Kodak invests heavily in the new technology, introducing its first digital camera in 1990. By 2000 it emerges as one of the leading digital imaging producers. In 2001 it makes the bold move to purchase an emerging photo sharing site called Ofoto. Embracing its historical tag line, “Share memories, share life,” Kodak rebrands Ofoto as Kodak Moments, transforming it into the leader of a new category called social networking, where people share pictures, personal updates, and links to news and information. In 2010, it attracts a young engineer from Google named Kevin Systrom, who takes the site to the next level. By 2015 Kodak Moments has hundreds of millions of users. Kodak still sells film to niche markets (and makes nice profits doing so), but the company’s center of gravity has clearly shifted to social networking. The company deftly manages the transition and emerges from a potentially disruptive shock a different, but vibrant, organization.

Wait—that didn’t happen.

Kodak did indeed invest in digital imaging and did indeed buy Ofoto, but instead of turning it into a vibrant social network Kodak focused on getting more people to print more pictures. It sold the business in 2011. It did indeed invest heavily in digital technologies; Sasson’s quotable line in 2008 that management’s response to his technology was, “That’s cute, please don’t tell anyone about it” was also cute but not particularly accurate. But seemingly Kodak was never able to fundamentally shift its business model, and as silver halide film began its inevitable decline, so too did the company. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2012.

It’s a sad story of lost potential. The American icon had the talent, the money, and even the foresight to make the transition. But instead it ended up the victim of the aftershocks of a disruptive change.

A Transformational Year for Media

On June 17, 1994, Americans are glued to their television sets watching O.J. Simpson, a charismatic retired football player who had appeared in movies and television commercials, riding in his white Ford Bronco while being chased by police. Simpson is accused of violently murdering his ex-wife and one of her friends, and the combination of violence and celebrity makes it catnip for viewers. This is the first time that television news producers, most notably Turner Broadcasting’s Cable News Network, break from actual news to cover second-by-second minutia of something so voyeuristic. It was a seminal moment in the media industry, and its effects are still being felt.

An even more important event took place later that same year when Marc Andreessen and his team introduced a beta version of the Netscape browser. Since the late 1960s, academics and defense officials had been experimenting with using a distributed network of computer connections to communicate and collaborate. The Netscape browser—coupled with Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of HyperText Markup Language (HTML) universal resource locators (URLs), along with a range of complementary innovations—allowed even the layperson to ride the so-called information superhighway. The disruptive effects of this internet-enabling technology reshaped the media business. The first to feel its effects were newspapers. Historically the scale economics of the printing press created significant barriers to entry, resulting in effective natural monopolies in many markets; most US cities had only one or two highly profitable papers. The rise of the commercial internet destroyed this business, with most newspaper companies decimated by 2000.

Well, not exactly. Certainly the newspaper companies felt some pain during the 2000–2002 US recession, but the years from 1994 through 2007 were actually quite good for most newspapers. Although the internet was stealing eyeballs, circulation remained relatively stable and advertising revenue continued to grow. The rise of classified-ad killers—such as craigslist (which offered free listings for apartments, jobs, and other, less savory things) and eBay—were nuisances. But when two of us (coauthors Clark Gilbert and Scott Anthony) presented a talk at a Newspaper Association of America meeting in Miami in January 2005, the dominant sentiment was that the industry had taken the best punch the internet could throw and still stood tall.

As legendary investor Warren Buffett likes to say, when the tide goes out you see who is swimming naked. The next US recession, in 2007–2009, showed the industry’s precarious position. From 1950 to 2005, industry advertising revenue grew from roughly $20 billion to $60 billion. By 2010, the market had fallen to $20 billion. Put another way, fifty-five years’ worth of advertising growth was eviscerated in a handful of years. Companies went bankrupt, jobs were lost, with the few remaining players staggering to find a sustainable path forward.

A Transformational Year for Mobile Handsets

In 2007 the Boston Red Sox, miraculously, celebrate their second World Series championship in four years after an eighty-six-year gap between their last two. Disney’s Pixar Animation Studios releases a movie about a rat who is also a chef, grossing more than $600 million worldwide, earning widespread critical acclaim and demonstrating why Disney paid Steve Jobs more than $7 billion in 2006 to acquire John Lasseter, Ed Catmull, Woody, Buzz, Nemo, Luxo Jr., and the rest of the Pixar team.

There were two darlings in the mobile handset industry. Nokia had emerged from bruising battles with Motorola and others as the clear market leader, with market share three times as big as that of the nearest competitor. In November, Forbes ran a cover story proclaiming, “One Billion Customers: Can Anyone Catch the Cellphone King?”

Um, yes. But not overnight. In fact, if you were an investor in Nokia, 2007 was indeed a very good year for you. Whereas the S&P was up by 5 percent that year, Nokia’s stock surged by 155 percent, trumping another industry competitor heralded for its innovation prowess: Canada’s technology darling Research in Motion (RIM), best known for its BlackBerry handset. RIM’s stock almost doubled during 2007. In what turned out to be a prescient interview with CBC in April 2008, RIM’s co-CEO, Jim Balsillie, said, “I don’t look up too much or down too much. The great fun is doing what you do every day. I’m sort of a poster child for not sort of doing anything but what we do every day . . . We’re a very poorly diversified portfolio. It either goes to the moon or crashes to the Earth.”

And crash both Nokia and RIM did.

In January 2007 Steve Jobs announced, and in June Apple launched, the iPhone. Dubbed the “Jesus phone” by worshippers, the phone created a media firestorm and immediately started showing up in the hands of celebrities. In November, Google, along with a range of handset manufacturers, formed the Open Handset Alliance, powered by Google’s Android operating system. Android’s origins trace to a $50 million acquisition Google made in 2005 of a young startup that had hot technologies as well as Andy Rubin, a noted talent in the wireless space. Google’s hope was that by making it easier for users to access the internet on mobile phones, it could expand its core advertising business.

In 2013, Nokia sold its handset business to Microsoft for more than $7 billion. Eighteen months later, Microsoft took a write-down of roughly $7 billion. RIM, renamed BlackBerry, saw its stock drop close to 95 percent from the 2008 Balsillie interview to 2015.

Kodak’s digital disruption took almost forty years to fully play out. Newspapers had about a dozen years of life after the internet shock. Nokia and RIM had only five years before great businesses painfully built over decades were ripped apart.

And thus the innovator’s clock accelerates.

In the HBO sword-and-sorcery series Game of Thrones, and the books by George R.R. Martin that inspired the show, the gritty Stark family has a saying: winter is coming. It isn’t winter that’s coming to your boardroom. It is disruption. Disruption is coming. And it is coming at an unprecedented pace and scale.

The Circle of Disruption

Yet there’s something oddly comforting in the industry case studies. It’s the way of capitalism, after all. A disruptive change hits a market, making what used to be complicated simple, and what used to be expensive affordable. Lumbering giants move too slowly, toppling under their own weight. Innovative upstarts, run by young, charismatic entrepreneurs, embrace the newness of the technology, creating new business models and indeed new organizational forms. The disruption breaks open a historically constrained market, bringing new solutions to millions, if not billions, of people. Then enterprising upstarts become lumbering giants, destined to be felled by the next generation of entrepreneurs. Cue the montage, play Elton John’s “Circle of Life” from The Lion King, and pass the popcorn.

Of course, if you’re a top executive in one of the companies confronting this kind of challenge, it is anything but entertaining. In fact, we believe that it is the greatest challenge facing leaders today. Creating a new business from scratch is hard, but executives of incumbents have the dual challenge of creating new businesses while simultaneously staving off never-ending attacks on existing operations, which provide vital cash flow and capabilities to invest in growth. The hastening pace of disruptive change means leaders have precious little time to respond. In fact, the time when leaders need to be most prepared for a change is right at the moment when they feel they’re at the very top of their game.

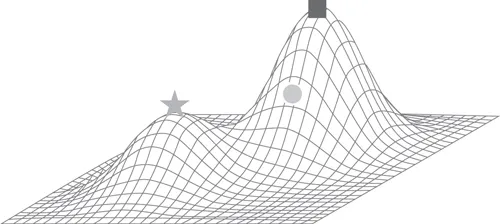

One metaphor that we’ve found helpful to frame the challenge is what’s known as a fitness landscape, borrowed from the field of population ecology. A fitness landscape is a representation of a topological map, with the height of a given hill showing its general attractiveness. Study the map in figure 1-1. Imagine you run the company represented by the square at the top of the highest mountain. You’ve done it. You’ve left your competition (represented by the circle) in the dust. You’re the top of the heap. The monarch of the mountain. From your commanding heights you can clearly see a new, disruptive upstart taking root (represented by the star). From your vantage point, you can see how small that hill is. It is inconsequential.

COMP: Insert Figure 1-1, “Industry topography, predisruption,” near here. Consider your strategic choices. You are in fact sitting on what is called a “local maximum.” Any strategy looks inferior to the one you’re currently following. Put in simple terms, there is no direction to go but down.

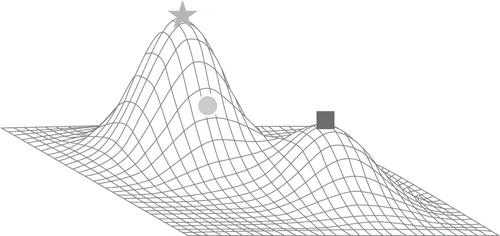

This phenomenon paralyzes leaders who own a position atop a historic hill. Unfortunately, the landscape is not static. In fact, disruption rearranges the strategic topography. You wake up one day and the landscape looks like the image in figure 1-2. Consider your options now. The disruptor (still a star) is too big and powerful to attack head on, so your best chance is to establish a foothold on its hill (the circle). But that strategy, and any other, looks materially worse than what you’re currently doing. Your square sits at the top of the hill, although it’s a much smaller one. Once again, there’s no direction to go but down.

COMP: Insert Figure 1-2, “Industry topography, postdisruption,” near here. FIGURE 1-1

Industry topography, before disruption

FIGURE 1-2

Industry topography, after disruption

This is tough stuff. And this is only about the fundamental decision to change strategy. Any leader who has gone through a reorganization or reinvention will tell you that, as hard as it is to decide to change, it is easier than actually making the change.

The term often used to describe what happened to Kodak, newspaper companies, and Nokia is creative destruction. The phrase is generally credited to economist Joseph Schumpeter from his landmark book Capitalism, Socialism and Demography. In that work he vividly described the “gale of creative destruction” that tears down established institutions. Schumpeter described the destructive power of this gale, coupled with the innovative creation spurred by entrepreneurs, noting, “[T]he problem that is usually being visualized is how capitalism administers existing structures, whereas the relevant problem is how it creates and destroys them.”

The emergence of a new hill creates tremendous growth for its creator. However, while we celebrate these vibrant gains, let’s stop and consider the losses when the transition involves the rise of a new company and the death of an old one. Thousands of jobs, if not tens of thousands, are displaced. Communities that grew up around enterprises are torn apart. Tens of thousands of years of accumulated know-how are lost. This kind of creative destruction carries a heavy transaction tax.

What if, instead, leaders could harness the underlying forces behind these kinds of changes to power new waves of growth for their companies? More specifically, what if a company sensed the gale coming early enough and built a wall to protect its core business? Or, even better, what if it built a wind turbine to harness the energy in the gale?

This book teaches you how to do just that.

Dual Transformation and the Disruption Opportunity

There are classic examples of companies that have risen to the challenge of disruptive change. Imagine IBM in the 1990s moving from products to services, or Apple during Steve Jobs’s second run as CEO moving from desktop computers to mobile devices and entertainment. There are other stories of companies that made dramatic shifts from one business to another, such as Nokia moving from rubber boots to mobile phones, or Marriott moving from a root beer stand to hotels.

We occasionally draw on these business classics, but our primary focus is on fresh, recent stories, many of which we have experienced firsthand either as advisers or as practitioners. Our experience allows us to present, for the first time, a detailed perspective of what strategic transformation looks like and, more important, what it feels like as you go through the journey. It’s like a virtual GoPro camera recording corporate leaders as they confront the hardest challenge in business.

Our bedrock case study comes from coauthor Clark Gilbert’s firsthand experience leading a transformation at Deseret Media. The Deseret (Utah) News is one of America’s oldest continually published newspapers, tracing back to 1850. Ultimately owned by the Mormon Church (which also owns the local KSL television station), the paper historically competed in Utah with The Salt Lake Tribune under what is known in the industry as a joint operating agreement, wherein the two companies share facilities and printing presses but have independent journalists, brand positions, and so forth. As the number 2 provider in its market, Deseret Media was hit particularly hard by the disruptive punch of the internet; between 2008 and 2010 the Deseret News lost nearly 30 percent of its print display advertising revenue and 70 percent of its print classified revenue.

In 2009, Gilbert—who had done his doctoral research...