![]()

Part One

Retailer Strategies Vis-à-Vis Private Labels

TWO FACTS are well known in the developed economies: there are too many brands, and it is an overstored environment. Yet, there always seems to be room for another successful brand or another successful retail chain. Witness the emergence of new iconic brands and successful chains that have either been launched or achieved dominance over the past two decades: Amazon.com, eBay, Nespresso, Old Navy, Red Bull, Starbucks, Tchibo, Trader Joe’s, Victoria’s Secret, and Zara. What makes a new entrant successful in the face of proliferating brands and stores is the ability to offer something distinctive and desirable with consistent quality. This is the challenge for retailer private labels—with so many brands already out there, what is their unique proposition to customers?

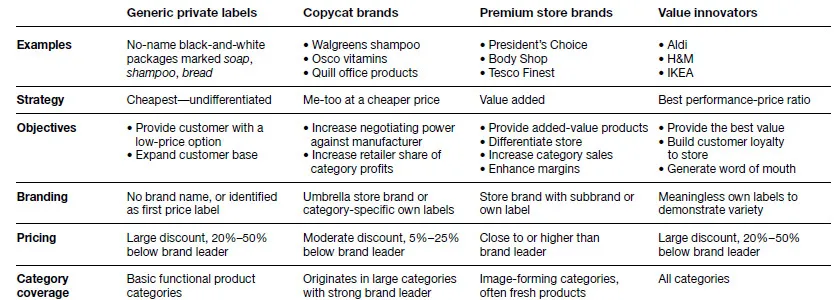

Finding a unique consumer proposition for private labels is exacerbated by the fact that most retailers today manage a multibrand portfolio of private labels rather than simply having a single store brand, such as Staples or Walgreens. Consider, for example, Wal-Mart, offering a premium Sam’s Choice brand and a cheaper Great Value brand of chocolate chip cookie, as well as many other private labels, like Equate OTC (over-the-counter, nonprescription) drugs and Ol’ Roy dog food. With multibrand portfolios, retailers have to develop a raison d’être for each of their own brands to exist. For each own label, retailers have to make decisions on the overall strategy, consumer proposition, and objectives for the proposed brand. Once these are articulated, then follow the more tactical decisions on branding, pricing, category coverage, quality, product development, packaging, shelf placement, and advertising or promotion.

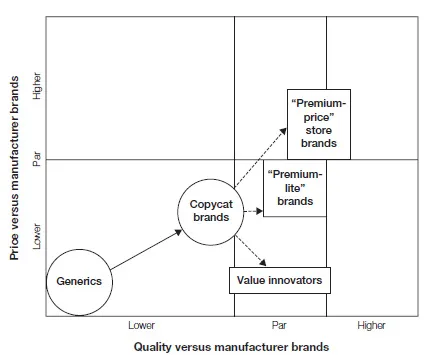

Usually, individual retailer store brands have one of four general consumer propositions with which to compete against manufacturer brands and other retailer brands. We refer to them as generics, copycats, premium store brands, and value innovators. Table I-1 outlines the differences between the four types of retail brands on various strategic and tactical dimensions. Of course, within these four types, over time, there are variations and evolution. And between the four types, at the edges, there are overlaps. Yet it is a useful scheme to understand individual brand strategies of retailers. The two traditional retailer strategies vis-à-vis private labels have been generics and copycats. In contrast, premium store brands and value innovator own labels are relatively new approaches by retailers. The separate and joint roles of these four types of private labels in retailers’ strategies are discussed in chapters 2 through 5.

At the end of the day, private labels are “merely” tools for retailers to achieve their strategic objectives: market share and, ultimately, profitability. As we argue in chapter 6, building market share for private labels involves a lot more than just price. Chapter 7 highlights the fact that the role of private labels in boosting retailer profitability is actually a lot more complex than the simple stratagem of increasing private label share in one’s assortment as much as possible—although this is a strategy followed by many retailers. Using real data and unique insights, we show that overemphasis of private labels may actually decrease retailer profitability.

TABLE I-1

Four types of private labels

![]()

TWO

Competing on Price with Traditional Private Labels

Percentage of all private labels that are copycats:

50 percent

DESPITE ALL THE BUZZ surrounding new developments in the private label landscape, such as premium store brands, we should not forget that traditional private labels—generics and copycats—are still the dominant types of store brands around the world. And retailers that venture into private labels typically start here. Hence it is appropriate to start this discussion of retail strategies vis-à-vis private labels with these still-ubiquitous types of store brand.

Generic Private Labels

Private labels, especially in the U.S., started as cheap, inferior products. Historically, they did not even carry the name of the store and were therefore called generics. Usually, the package with black letters on a white background simply identified the product, like paper towels or dog food. Most consumers saw them for what they were—undifferentiated, except in their poor quality, but at a very low price. These cheap, shoddy products, however, did offer lower-income and price-sensitive customers a purchase option, and as a result enabled the retailer to expand its customer base. Generics were all about the lowest possible price.

In terms of supply chain, generics did not add a lot of complexity for the retailer. They appeared only in the basic, functional, low-involvement categories like paper goods and everyday canned foods. And within each category, they were usually offered in one size and one variant only, thereby accounting for relatively few additional stock-keeping units (SKUs) for the retailer. Retailers rarely ran price promotions on generics. The retailers generally put these generic products out for bid to manufacturers, either those specializing in private labels or brand manufacturers selling their excess capacity.

The Decline and Revival of Generics

Typically, generics did not account for a large proportion of the retailer’s volume, and as a result they were not strategically important to the retailer. Generics suffered from poor shelf placement, usually on floor-level, less visible, retail shelves. Over time, generics have lost shelf space and importance to copycat store brands, premium store brands, and value innovator own labels, as shown in figure 2-1.

There has, however, been a recent resurgence in the generics consumer proposition in Europe, though not as the old “black and white” generics. Many European retailers, with advanced private label programs, are converting what used to be generics into an important element of their multibrand portfolios. To respond to the intense price pressure from hard discounters like Aldi, Lidl, and Netto, mainstream retailers have been forced to develop a dedicated private label that identifies the lowest price at which a product is available in the store. By having such a first-price private label line, traditional retailers such as Albert Heijn, Carrefour, Delhaize, and Sainsbury can demonstrate that they have a basket that is price competitive against the hard discounters.

Three Branding Strategies for Generics

These price-fighter private labels may be a store brand with a subbrand, a stand-alone own brand, or a consortium brand. For example, Tesco and Sainsbury have used the store brand with subbrand approach to anticipate and limit the onset of hard discounters in the United Kingdom. Tesco has a Value line, while Sainsbury’s Low Price economy range (see figure 2-2) encompasses more than three hundred food and household products.

South Africa’s Pick ’n Pay, one of Africa’s largest supermarket chains with more than three hundred supermarkets and fourteen hypermarkets in southern Africa, has its No Name line to fight superefficient Shoprite. To counter quality concerns often associated with generics, there is a money-back guarantee on the packaging of the No Name, stating that if the customer is not satisfied, “we will gladly give you DOUBLE THE MONEY BACK” (capitals in the guarantee). To give further credibility to this guarantee, it is signed by Pick ’n Pay’s legendary founder, CEO Raymond Ackerman.

FIGURE 2-2

Sainsbury cheap white labels

Source: Jan-Willem Grievink, “Retailers and Their Private Label Policy” (presentation given at the 4th AIM Workshop, June 29, 2004). Reproduced with permission.

In contrast, in 2003 Carrefour was finally forced to introduce a line of low-priced private label goods under a stand-alone brand name “1” after losing significant market share in France to hard discounters. The assortment under “1” now exceeds two thousand products and generates $1.6 billion in annual sales for Carrefour. The brand attempts to be 6 to 7 percent cheaper than the hard discounters and adopts the everyday low prices (EDLP) strategy, but it is doubtful that it generates any significant profits for Carrefour.

To leverage economies in sourcing beyond those that would otherwise be available to a single retailer, Ahold and eight other European retailers have formed an alliance that negotiates very hard with private label manufacturers on hundreds of products, from paper goods to soft drinks, which are then sold under the consortium brand Euroshopper.1

Such generics or a first-price range of products do help the retailer serve the price-sensitive consumer and limit the onset of price-oriented competitors. However, it is not entirely clear that these generics generate the required profitability to justify their shelf space. Furthermore, they may end up cannibalizing the retailer’s own higher-priced and higher-margin private label range. Yet, the hope for retailers is that such a line attracts price-conscious customers, whose shopping basket ultimately ends up with a mix of low-margin generics as well as some higher-margin nongeneric products. Thus, while the first-price range may not be very profitable in its own right, it may still attract profitable shoppers.

Copycat Store Brands

Generics, especially in the U.S., lost their share of the shelf space to retailer private labels that often carry the name of the retailer as a brand, referred to as store brands. These store brands are copycats in the sense that they imitate the leading manufacturer brands in the category. For example, Wal-Mart’s Equate brand of dental rinse compares itself on the front of the package to its branded competitor, Plax. Similarly, Target’s dental rinse product explicitly references a leading manufacturer brand, Wintergreen Listerine. The drugstore chains CVS and Walgreens also have similar copycat store-branded mouthwashes.

Copycat Brand Strategy

Often, copycat store brands are uncomfortably close in terms of packaging, as the Cif (Unilever) and Nescafé (Nestlé) examples demonstrate in figure 2-3. Placing these look-alike store brands adjacent to the leading brand encourages both brand comparison and brand confusion on the part of shoppers.

FIGURE 2-3

Retailer copycat brands

Source: Photos by Jean-Noel Kapferer, 2006. Reproduced with permission.

Retailers aggressively promote copycat brands using price promotions and comparative messages. For example, in August 2003, Quill, the direct office products retailer, in an online ad promoted a bundle of fourteen Quill brand products for $29.99 against the comparable manufacturer brand items for $141. No wonder Quill private labels now account for one-third of its business.2

To ensure quality, retailers analyze the contents of a leading manufacturer brand and then re-create the product step by step, a process called reverse engineering. In this sense, they are free riding on the manufacturer’s innovation, research, product development, and image-building efforts for its brand. Since there are few research and development or sales and marketing expenses for the retailer, and the products are aggressively outsourced for low-cost manufacturing, the price on such copycat store-branded products is considerably lower than the referent manufacturer brand while still delivering high margins to the retailer, at least in percentage terms. For example, Reckitt Benckiser’s Vanish is priced in the Netherlands at $11.50 per kilogram, compared with $6.34 per kilogram for the Kruidvat store-branded copycat.

Copycats Drive Profits from Manufacturers to Retailers

Copycat store brands by retailers do not face the risks associated with new product introduction, because they only introduce such copycat brands once the manufacturer’s new product has become a hit. For example, only recently have retailers begun launching store-branded flavor...