eBook - ePub

Reinventing Jobs

A 4-Step Approach for Applying Automation to Work

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Two experts on human capital and work provide a practical framework for addressing the leadership and organizational challenges of automation.

- Of all the books available on automation and artificial intelligence, this book provides the most "on the ground level" view on what leaders need to do to proactively drive the changes in how work gets done in their organizations.

- Explains how automation requires organizations to rethink what a "job" really is and how it should be structured, in much the same way that Hammer and Champy's "reengineering the corporation" forced organizations to rethink how a "business process" should be structured.

- Helps leaders cut through all the noise and hype around automation, AI, and robotics, and helps them become more capable of applying various types of work automation and AI to jobs in their organizations with a structured 4-step approach

- Explains the three ways that jobs can be automated—robotic process automation, cognitive automation, and social robotics—and shows how each technology fits a different kind of work and has different implications for jobs and for the organization

Audience:

- Leaders in all industries and functions who want to understand how to employ AI to improve performance and drive change in how work gets done in their organizations.

- HR professionals and organization consultants.

- Anyone in organizations who wants to understand how their work and jobs may change.

Announced first printing: 20,000

Laydown goal: 6,000

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reinventing Jobs by Ravin Jesuthasan, John Boudreau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

At a recent conference on AI and the future of work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, experts concluded that technology “both creates and destroys jobs,” that labor productivity growth has actually slowed despite technological advances, and that to realize the benefits of automation, we will need to reinvent organizations, institutions, and metrics.1 Technologies like self-driving cars, chatbots, automated parking lot attendants, and robotic home caregivers are enticing and attention grabbing, but experts say that the pivotal factor in realizing their value is increasingly how leaders optimize the combinations of human and automated work, and then organize and lead to support those combinations.

Part One describes our four-step framework for achieving that optimization. Each chapter describes a vital component of the framework. Then, chapter 4 pulls them all together to show their combined ability to reveal new and more optimal solutions. Every chapter uses actual examples to show how you can better reach your strategic goals by focusing more clearly on work-automation optimization.

To show how the four steps of our framework build on each other, each of the first four chapters begins with a vignette that continues the story of the automatic teller machine (ATM) that we opened with in the introduction. Each chapter relates a new facet of the ATM story and illustrates the ideas that you will see in that particular chapter.

ONE

Deconstruct the Job

Which Job Tasks Are Best Suited to Automation?

Here’s a brainteaser: You are given a candle, a box of tacks, and a book of matches. How do you attach the candle to a wall so that you can light it without dripping wax onto the floor below?

The solution to Duncker’s candle problem is to deconstruct the box of tacks into its parts (box, tacks).1 Then you’ll see that the tacks can attach one side of the box to the wall and attach the candle to the bottom of the box. In experiments, people who receive the box with the tacks inside solve the problem far less often than those given the box with a separate pile of tacks next to it.

What does this have to do with work automation? Work is constructed into job descriptions similar to the box full of tacks. The job descriptions become a repository of competencies, performance indicators, and reward packages. Soon, leaders, workers, and others see the job and its components as one indivisible thing, like seeing the box full of tacks as one thing. This tendency to think of jobs as fixed repositories obscures powerful opportunities to optimize work automation. It leads to the common but overly simplistic question, “How many workers doing a job will be replaced by automation?” The true pattern of work automation is only revealed in the deconstructed work tasks, not the job.

Just as you must take the tacks out of the box to solve the candle problem, you must take the tasks out of the job and then reinvent the job to solve the work automation problem.

Let’s return to the ATM story to see how this works.

The Wrong ATM Question: “How Many Teller Jobs Can Be Replaced?”

Imagine you lead the workforce of a retail bank in the 1970s. Your technology analysts have run the numbers and estimated huge cost savings from replacing the human tellers with ATMs. In fact, because teller machines need not be attached to a full bank branch, your technology planners estimate that eventually you can cut costs even more by reducing the number of full branches, creating mini-branches consisting solely of ATMs. Customers who need services beyond the teller machines will go to one of the fewer traditional bank branches. The technologists are also enthusiastic about risk reduction, because teller machines make fewer mistakes, like failing to complete necessary paperwork or coding transactions incorrectly. They wax eloquent about enhancing the customer experience, because ATMs can process transactions faster so customers spend less time waiting in line. These potential benefits are enticing, but as history shows, simply replacing human tellers with automated machines wasn’t the optimal solution.

The first step to a better solution is to take apart, or deconstruct, the job into work elements or tasks. (The sidebar “Work Elements of the Job of Bank Teller” shows one example of how the deconstructed teller job might look.)

Some tasks, such as processing cash withdrawals, are very amenable to the automation of ATMs. Others, such as counseling customers whose accounts have been frozen due to overdrafts, are not amenable to automation. An ATM can hardly deal with customer frustration and anger.

Deconstructing the teller job into its elements also reveals that job elements could be automated in different ways. Human bank tellers assisting a customer completing a simple transaction can detect when that customer might be receptive to other banking services. A recent Atlantic article featured an interview with Desiree Dixon, a member-service representative at the Navy Federal Credit Union in Jacksonville, Florida, who described her work: “[W]hen you walk into a Navy Federal, [the staff] really understands what you go through as a military spouse or your family being in the military. Unless you’re in that situation, or you have people in relation to that, there isn’t that understanding. When your husband or your sister is out to sea and they’re deployed, and you’re trying to get business taken care of—you may have a power of attorney and it’s in their name. Navy Federal really understands that those things occur.”2

Now you can see more clearly how to group the tasks: some are repetitive (providing requested cash; verifying sufficient funds), while some are variable (collaborating with product designers to improve products and processes). Some require human interactions, empathy, and emotional intelligence (conversing with customers; counseling those who have insufficient funds), while some are done independently (calculating cash balances). Some are physical (giving cash to customers), and some are mental (identifying appropriate additional bank services). You realize that these categories reveal which tasks are very compatible with replacement by an ATM (such as repetitive-independent-physical), and which must be done by humans or automated very differently (variable-interactive-mental). (See table 1-1.)

TABLE 1-1

Work elements categorized by their dimensions

Deconstructing Jobs into Work Elements

As the ATM example illustrates, you must deconstruct jobs into their key elements and not think in terms of replacing entire jobs. Those elements will reveal the optimization patterns, often hidden when the work is trapped in a job description. That does not mean that jobs will disappear, but rather that they will be reinvented, as work that was aggregated into a “job” is constantly reconfigured and continuously deconstructed and reconstructed. Over time, some work elements will be removed from the job as they are transferred to other work arrangements or automation.

The remaining work tasks may no longer make up a full-time job. However, work automation isn’t just about optimizing one job at a time. Groups of jobs are related, so work automation requires optimizing the related work tasks across several jobs. In a related group of jobs, each job’s content may be reduced by automation, but the remaining human tasks from several related jobs may be combined into a new, reinvented full-time job. Our examples will often focus on a single job for illustration, but you can use the same tools in the more realistic situation where work automation should apply to groups of jobs with related tasks.

How do you find the component tasks within jobs? There are many frameworks. You may be using several of them. You can find the tasks that make up jobs in job descriptions and competency lists. You can also sometimes find them in performance goals and reward components. One online library of work tasks, spanning thousands of different kinds of jobs, is O*Net. Its website says, “[T]he O*NET database, containing hundreds of standardized and occupation-specific descriptors on almost 1,000 occupations covering the entire US economy. The database, which is available to the public at no cost, is continually updated from input by a broad range of workers in each occupation.”3 Figure 1-1 is an adaptation of a graphic produced by AlphaBeta Analysis using data from O*Net to illustrate the automation compatibility of tasks within jobs. As you can see, each job contains many different tasks, and each task has different automation compatibility. Asking if a job is compatible with automation is meaningless, compared to asking how automation compatible each deconstructed task is.

FIGURE 1-1

Automation compatibility of tasks within jobs

The impact of automation is best understood by breaking the economy down into tasks

Source: This work is a derivative of “The Impact of Automation Is Best Understood by Breaking the Economy Down into ‘Tasks,’” by O*net, Alphabeta Analysis, used under CC BY 4.0.

What Makes a Task Automation Compatible?

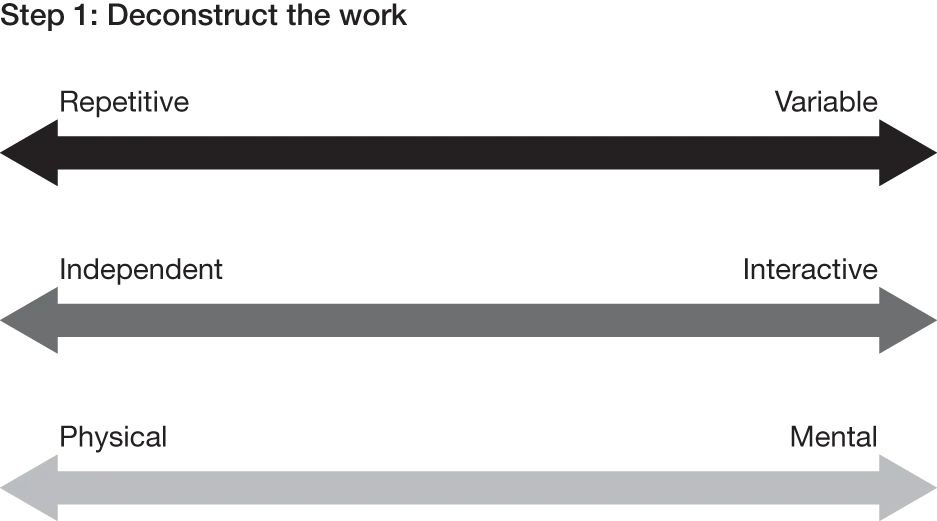

How do you measure the ease of automating a task? We believe there are three fundamental characteristics, as shown in figure 1-2.

FIGURE 1-2

Three dimensions that determine automation compatibility

Repetitive versus Variable?

Repetitive work is often predictable, routine, and determined by predefined criteria, while more variable work is unpredictable, changing, and requiring adaptive criteria and decision rules.

Most of the work tasks of credit analysts are repetitive. They gather and synthesize similar data for every loan application. They look for the same red flags in each piece of customer data that is pulled from bank records, credit rating agency data, government records, and social media. Generally, repetitive work is more automation compatible with well-established solutions such as RPA, which we describe in chapter 3. RPA can perform such analyses as much as fifteen times faster, with almost no errors. On the other end of the continuum, the work of a human resources consultant is highly variable. Every client situation is different and every problem is unique. This consultant works with analytical tool kits, change management frameworks, and process design techniques that must be customized to diagnose unique problems and solutions. Such work is generally less amenable to automation, but advances in cognitive automation might automate some analytical tasks or learn from previous client engagements.

Independent versus Interactive?

Independent work requires little or no collaboration or communication with others, while work performed interactively involves more collaboration and/or communication with others, and relies more on communication skills and empathy.

Accountants preparing statutory reports for regulators using prescribed templates and decision rules are doing primarily independent work. They can gather data from various sources, synthesize their findings, apply accepted analytical tools, and produce reports with their findings without engaging another person. A good portion of such work is automation compatible using well-established methods. For example, RPA could do the information gathering and synthesis, while AI could do much of the analysis and produce certain basic reports. Call-center agents, on the other hand, are doing interactive work, matching their work to each caller’s unique emotions, needs, and style of communication. Interactive work is gen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION: AI and Robotics Are Here. Now What?

- PART ONE: Optimizing Work Automation: A Four-Step Framework

- PART TWO: Redefining the Organization, Leadership, and Workers: Automation Implications beyond Reinventing Jobs

- Appendix

- Notes

- Index

- About the Authors