![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Business Scope

In 1960, Theodore Levitt, a Harvard Business School professor, published a provocative paper in Harvard Business Review in which he argued that companies were too focused on products and not enough on customer needs. To help managers address this problem, he asked, “What business are you really in?”1 More than five decades later this fundamental question has become even more important, as companies are moving from products to platforms and as industry boundaries are getting blurred. Yet even though the majority of firms are trying to become customer-centric, it is not uncommon to hear senior executives, be it from General Motors or Walmart, define their businesses, their industries, and their competition by the products they produce and sell.

Let’s look to Amazon to see the advantage of heeding Levitt’s advice.

What Business Is Amazon In?

When Amazon first launched its website, in July 1995, founder Jeff Bezos’s goal was to use the internet to sell books at low prices. He created a virtual store with lower fixed costs and a larger inventory than those of most brick-and-mortar bookstores. The concept quickly became popular, and Bezos realized that consumers shopping for other types of goods might also appreciate this concept. So he began adding dozens of categories to Amazon’s online assortment, including music, DVDs, electronics, toys, software, home goods, and many more. Amazon’s low prices and large selection, and the convenience online retailing provided consumers, posed a significant threat to traditional retailers like Best Buy, Toys “R” Us, and Walmart.

Five years later Amazon opened its site to third-party sellers, who could post their products on Amazon’s site for a modest service fee. This move was a win-win: third-party sellers increased Amazon’s assortment without Amazon having to stock extra inventory, and sellers got access to the ever-increasing pool of consumers who enjoyed shopping on Amazon’s site. Adding third-party sellers also transformed Amazon from an online retailer to an online platform, which required Amazon to develop new capabilities of acquiring, training, and managing sellers on its sites without losing control or damaging customer experience. And its competitive set expanded to include eBay, Craigslist, and others.

Other online retailers, such as Flipkart in India, are undergoing a similar transition and realizing that this seemingly simple move from an inventory-based model to a marketplace model requires a significant shift in the capabilities and operations of the company.2

The introduction of iTunes, in 2001, dramatically changed consumers’ behavior as they started downloading digital music instead of buying CDs in a store. Recognizing this trend, Amazon launched its video-on-demand service, initially called Unbox and later renamed as Amazon Instant Video, almost a year before Netflix introduced video streaming. Once again Amazon followed its customers and shifted from selling CDs and DVDs to offering streaming services that required it to develop new capabilities and pitted it against a new set of competitors, such as Apple and Netflix.

In 2011, in partnership with Warner Bros., Amazon launched Amazon Studios to produce original motion-picture content. Suddenly it was competing against Hollywood studios. Why does it make sense for Amazon, which started as an online retailer, to move in this direction? Because video content helps Amazon convert viewers into shoppers. In a 2016 technology conference near Los Angeles, Jeff Bezos said, “When we win a Golden Globe, it helps us sell more shoes.”3 According to Bezos, the original content of Amazon Studios also encourages Prime members to renew their subscription “at higher rates, and they convert from free trials at higher rates” than Prime members who do not stream videos.4 Launched in 2005, Prime offers free two-day shipping for a subscription fee, which started at $79 a year and was later increased to $99 a year. By 2017, Amazon had almost 75 million Prime members worldwide.5 Not only does the subscription fee generate almost $7.5 billion in annual revenue for Amazon, but Prime members also spend almost twice the amount of money than other Amazon customers do.6 In addition to creating loyalty among Prime members, original content is also a means of attracting new customers. In 2015, Amazon’s CFO Tom Szkutak credited Amazon’s $1.3 billion investment in original content as a key driver for attracting new customers to other parts of Amazon’s business, including Prime.7 In 2017, Amazon spent almost $4.5 billion on original video content.8

But Amazon’s business scope did not end with retailing and content. In 2007, Amazon released the Kindle, almost three years ahead of the iPad. Now Amazon, which started as an online retailer, was in the hardware business. The Kindle was designed to sell ebooks as consumers shifted from physical products to digital goods. It is important to recognize that Amazon’s strategy for the Kindle is quite different from Apple’s strategy for the iPad. Apple makes most of its money from hardware, whereas Amazon treats the Kindle as a “razor,” selling it at a low (or even break-even) price in order to make money on the ebooks, which would be akin to the “blades.” As consumers started spending more and more time on their mobile devices, Amazon launched its own Fire phone in July 2014. It failed to gain traction, but was pursuing that market a mistake? Perhaps. However, the upside from a successful launch would have been enormous.

More recently, Amazon launched additional devices: Dash buttons, which let users order products from over a hundred brands when users’ supplies get low, and Echo, a voice-activated virtual assistant, which can be used to stream music, get information, and of course, order products from Amazon in an even more convenient fashion.9 Echo was launched in November 2014, and within two years Amazon had sold almost eleven million Echo devices in the United States and developers had built over twelve thousand apps or “skills” for this device. As voice increasingly becomes the computing interface for consumers, Amazon is well positioned with Echo.

Amazon also started its own advertising network, which put the company squarely in competition with Google. Amazon’s large customer base, and more specifically the company’s knowledge of consumers’ purchasing and browsing habits, provides Amazon with a rich source of data for targeting its customers with relevant ads. While Google only knows a consumer’s intention to buy a product, Amazon has information on whether or not a consumer actually bought a product on its site—highly valuable information for product manufacturers, which is encouraging them to shift digital advertising dollars to Amazon. This shift has allowed Amazon to generate almost $3.5 billion of ad revenue in 2017.10 But an even bigger goal for Amazon is to replace Google as a search engine for products, so that customers start their product search on Amazon rather than on Google. This would not only reduce Amazon’s ad spend on Google but would also give Amazon tremendous market power. In October 2015, a survey of two thousand US consumers revealed that 44 percent go directly to Amazon for a product search, compared with 34 percent who use search engines such as Google or Yahoo.11 Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, acknowledged this shift. “People don’t think of Amazon as search,” said Schmidt, “but if you are looking for something to buy, you are more often than not looking for it on Amazon.”12

Perhaps the most controversial choice was Bezos’s decision to enter the cloud-computing market with the launch of Amazon Web Services (AWS). Suddenly a completely new set of companies—for instance, IBM—became Amazon’s competitors. What is an online retailer doing in cloud computing? AWS helps Amazon scale its technology for future growth. It allows Amazon to learn from other e-commerce players who use its platform. And it enables Amazon to leverage and monetize its excess web capacity. Effectively AWS is a way for Amazon to build its technology capability to become one of the largest online players and monetize that capability at the same time.

However, this was certainly a risky move and many experts questioned Bezos’s decision. A 2008 Wired magazine article criticized this decision. “For years, Wall Street and Silicon Valley alike have rolled their eyes at the legendary Bezos attention disorder,” wrote Wired. “What’s the secret pet project? Spaceships! Earth to Jeff: You’re a retailer. Why swap pricey stuff in boxes for cheap clouds of bits?”13 Bezos had a pithy response to AWS critics: “We’re very comfortable being misunderstood. We’ve had lots of practice.”14 In the fourth quarter of 2017, AWS generated over $5 billion in revenue, representing annual revenue of more than $17 billion and 43 percent year-over-year growth.15

Amazon’s success in broadening the scope of its business while continuing to focus on consumer needs is undeniable: Since its inception, Amazon has grown at a staggering pace, with almost a 60,000 percent increase in its stock price.

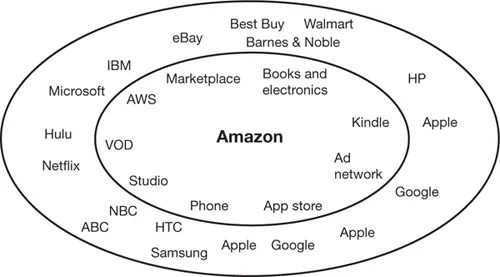

Define Your Business Around Your Customers, Not Your Products or Competitors

Amazon’s varied products and services, and the company’s correspondingly numerous and varied competitors, can be seen at a glance in figure 1-1. As an online retailer, Amazon competes with Barnes & Noble, Best Buy, and Walmart. As an online platform, Amazon competes with eBay. In cloud computing, it battles for market share with IBM, Google, and Microsoft. In streaming services, it has Netflix and Hulu as formidable competitors. Amazon Studios puts the company up against Disney and NBC Universal Studios. Its entry into mobile phones put it in the crosshairs of Apple, HTC, and Samsung. Its ad network made it Google’s rival.

FIGURE 1-1

Amazon’s business and its competitors

Most companies define their business by either their products or their competitors—for example, you may consider yourself in the banking business or the automobile industry. But it is hard to define Amazon in this traditional fashion. Amazon expanded its scope around its customers.

Redefining your business around customers is not limited to technology companies. John Deere, the heavy-machinery and farming-supply company, was founded in 1837 by a blacksmith who sold steel plows to farmers.16 By 2014, the company had $36 billion in sales worldwide and employed nearly 60,000 people.17 For decades, John Deere had been very successful selling its heavy machinery to farmers and construction companies, but in the early 2000s the company began adding software and sensors to its products. Its newest farming equipment includes guided-steering features so accurate that the equipment can stay within a preset track without wavering more than the width of a thumbprint.18 Later, John Deere formed two new divisions: a mobile-technology group and an agricultural-services group.

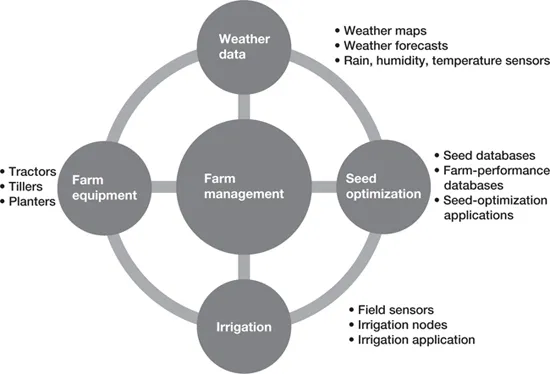

By the mid-2000s, John Deere had collected data from over 300,000 acres to help farmers optimize their fertilizer use.19 Soon the company transitioned from a farm-equipment manufacturer to a farm-management company that provided predictive maintenance, weather information, seed optimization, and irrigation through remote sensors (see figure 1-2). The company is planning to open the platform’s application programming interfaces (APIs) to outside developers, so that the information can be used in new ways.20

FIGURE 1-2

John Deere’s transformation

Source: Adapted from Michael E. Porter and James E. Heppelman, “How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Competition,” Harvard Business Review, November 2014.

Automobile companies, which used to see themselves as being strictly in the business of manufacturing and selling vehicles, have to wake up to the new competition from ride-sharing companies like Uber, which are providing mobility without the need to own or even lease a car. Now, as a defensive move, all automakers are positioning themselves within the “mobility” business and offering their own ride-sharing services, even though these services have the potential to reduce the demand for cars, a concern shared by most auto manufacturers. However, these services, such as Mercedes car2go and BMW DriveNow, also have the potential to generate interest among millennials, who may not have considered these brands otherwise but who will do so on a low-cost, trial basis, possibly leading to greater brand loyalty in the future.

Competition Is No Longer Defined by Traditional Industry Boundaries

It should be clear from the discussion so far that competition is no longer defined by traditional product or industry boundaries. The rapid development of technology is making data and software integral to almost all businesses, which is blurring industry boundaries faster than ever before. In a 2014 Harvard Business Review article, Michael E. Porter and James E. Heppelmann suggested that smart, connected devices—or the internet of things—shift the basis of competition from the functionality of a single product to the performance of a broad system, in which the firm is often one of many players.21

Typically new players, either startups or companies from different industries, enter a market and catch incumbents by surprise. Amazon surprised Google by becoming the dominant competitor in the search market. Apple is hiring automobile engineers at a rate that is scaring the auto industry. Netflix and, more recently, streaming services by HBO and CBS are causing concern for Comcast and other cable players.

Often incumbents leave an opening for new players by ignoring a shift in customer needs in response to changes in technology. Netflix changed customers’ expectations about on-demand streaming, and although cable providers eventually pursued the so-called TV Everywhere concept to allow their subscribers to stream content anywhere, it took them several years to develop this service, and it is still a work in progress. During a conference in late 2015, Reed Hastings, Netflix’s CEO, said, “We’ve always been most scared of TV Everywhere as the fundamental threat. That is, you get all this incredible content that the ecosystem presents, now on demand, for the same [price] a month. And yet the inability of that ecosystem to execute on that, for a variety of reasons, has been troubling.”22 Had Comcast understood the shift in customer needs and transformed its business around those needs, it might have prevented the threat of cord-cutting (which is cable customers canceling their subscriptions in favor of such streaming services as Netflix, Hulu, and HBO Now). Similarly, Uber might not have been so successful had taxi companies kept in touch with consumer needs and provided consumers a convenient way to order and pay for taxi rides.

Competitive Advantage No Longer Comes from Low Cost or Product Differentiation

In 1979, Michael Porter, one of my colleagues at Harvard Business School, published a l...