![]()

CHAPTER 1

“Remarkably Muscular and Well Made” or “Covered with Ulcers”

Enslaved Black Men’s Bodies

I puts de feet ’gainst him and give him a shove and out he go on de floor ’fore he know what I’s doin’. Dat nigger jump up and he mad. He look like de wild boar. He starts for de bunk and I jumps quick for de poker. It am ’bout three foot long and when he comes at me I lets him have it over de head… . Dat night when him come in de cabin, I grabs de poker and sits on de bench and says, “Git ’way from me, nigger, ’fore I busts yous brains out and stomp on dem.” He say nothin’ and git out.

—ROSE WILLIAMS

When Rufus attempted to lie down in his and Rose’s bunk for the first time his body paid a price. Rose used physical violence to discourage Rufus from crawling into bed with her, giving him a shove with her feet and hitting him in the head with a metal rod. The account as told by Rose rightly positions her as a victim, but we should not overlook that Rufus was also placed in a position that made him vulnerable to his enslaver. He had been kicked, hit over the head, sent out of his cabin, and violently threatened. All this occurred because the people who held legal rights to his body determined that he should reproduce by setting up a household with Rose. In the eyes of the society, his body was theirs to control. They commanded both his labor and his intimate life, as countless masters and mistresses had done to enslaved men for generations.

His enslaver’s decision to place Rufus in this situation held important meaning for Rufus as an enslaved man. Scholars have shown that the bodies and the physical capabilities of many enslaved men held important meaning for norms of masculinity. The body was central for understandings of masculinity. Kathleen Brown argues that because they were denied other means of propertied manliness, “the bodies of enslaved men—or, more precisely, the social persons rooted in those bodies—were more crucial to the meanings and experience of their manhood than was the case for other men.”1 Other scholars have similarly found specific areas in which enslaved manliness was expressed through physicality. The bodies of enslaved men were controlled by enslavement, but they also held keys to manliness. This chapter argues that enslaved men’s bodies were symbols of enslaved manhood and sites of violation. Enslaved men were poked and prodded on the auction block; objectified in various cultural forms, including abolitionist literature; and scrutinized, vilified, and tortured by masters and mistresses.

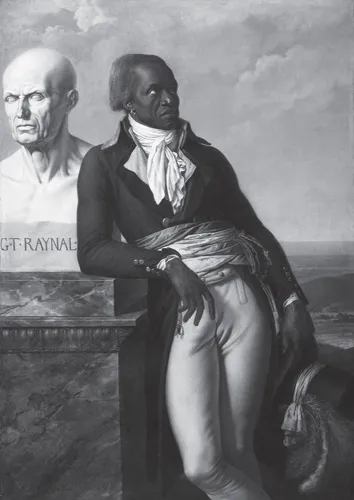

The 1797 portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a formerly enslaved captain in the Haitian Revolution and member of the National Council in France, captures Western cultural adoration of black masculinity (fig. 3). Painted by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, Belley stands in full formal uniform as a representative of Saint-Domingue to the French Convention. A landscape, presumably Haiti, is visible in the distant background. He leans against a marble pedestal, on top of which is a bust of philosopher and abolitionist Guillaume-Thomas Raynal. The painting, done in the style that was popular for prominent politicians and military leaders at the time, illustrates the power of presence associated with men of African descent. Scholars have noted that the image is remarkable for its presentation of a new French subject—a black man—painted as refined and in honorable dress and a classical pose.

The portrait also captured the culture’s positive assessment of black male sexuality as potent and desirable. Some art historians have even speculated that the artist must have been attracted to Belley, or at least admired him, as his genital outline is so undeniably present and further highlighted by the positioning of his hand and the sumptuously painted fabric of his pants.2 It is not possible to know if the artist enhanced what he saw to underscore his depiction of Belley’s virility. Belley may well have played upon the culture’s fascination with black men and their sexuality by wearing his pants in a manner that was more revealing than concealing, refusing to be ashamed of his manhood and employing the provocative power that it carried.

Belley’s portrait was unusual for the period. Few black men were the subject of such paintings, but it was typical of cultural representations of enslaved men, who were at times described in terms that emphasized idealized male power. John Saillant’s work on the eroticization of the black male body in early U.S. abolitionist literature shows that whites found sexual appeal in black male bodies. He notes that this literature idealized black male bodies in a manner that included an unusual focus on height, musculature, and skin color. Accounts in late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century American publications like the American Universal Magazine and the Philadelphia Minerva described black male characters as “the blackest, the best made, the most amiable,” “beautiful in shape as the Apollo of Belvedere,” and “tall and shapely.”3 Numerous abolitionist images fixated on the black male body as perfection, highlighting muscular bodies and, in almost pornographic detail, exposed buttocks enduring unjust abuse and degradation. Black abolitionist publications also described men’s bodies in prose that evoked sympathy. The Colored American, for example, included this description of an enslaved man: “Jack knelt down—not a muscle of his countenance quivered—he was entirely naked, and was a remarkably muscular and well made man. He looked like a fine bronze statue.”4 Another account, this one included in Frederick Douglass’s North Star, described one man by his “strength of limb, the roundness of muscle, mind, tender affection, sympathy” in efforts to combat slavery; such details served to underscore the moral injustice of enslaving these men.5 In another example, one man was described as “well proportioned” and “muscular” to distinguish him from others.6

FIGURE 3. Anne- Louis Girodet de Roussy- Trioson, Portrait of Jean- Baptiste Belley, Deputy of Santo Domingo to Convention of France, 1797. The portrait of Captain Belley, hero of both the American and Haitian revolutions, celebrates the accomplishments of a formerly enslaved man while also undercutting them by depicting him in a manner that uses sexuality to signal that black men were inherently uncivilized. Photo: Gérard Blot. © rmn–Grand Palais / Art Resource, N.Y.

Strength and power figured as measures of manliness also within slave communities, especially among enslaved men. Competitive fighting and wrestling among men served to highlight physical power as a marker of dominant manliness.7 Formerly enslaved men commented on power, strength, height, and musculature, often noting exceptional height in their recollections: “There was on one plantation, a slave about thirty years of age and six feet high, named Adam.”8 Frederick Douglass’s 1852 novel, The Heroic Slave, included an arresting description of the hero, Madison. “Madison was of manly form,” wrote Douglass, “tall, symmetrical, round, and strong.” He continued: “In his movements he seemed to combine, with the strength of the lion, a lion’s elasticity. His torn sleeves disclosed arms like polished iron.”9 Josiah Henson, for example, was proud of his ability to run, wrestle, and jump better than his peers and viewed his own body with admiration, calling himself a “robust and vigorous lad.” Others spoke about the impressive bodies of fathers and kin. William Smith, for example, boasted that his father was “very strong” and that he was “all muscle.” Lussana analyzes these bodies as “‘reclaimed’” and argues that they bonded men within the community and reinforced their sense of masculinity.10

Muscular physiques were prized for labor. They were also seen as an indicator that a man could ably fulfill the masculine ideals of competitiveness and serve as the protector of his loved ones. Some enslaved men protected their own honor as they bested other men who pursued their loved ones. One formerly enslaved man recalled how his father was able to successfully beat another who he believed had been too friendly with his wife. The son’s own masculine pride was evident as he described his father as a “big and strong” man and the man he attacked as “small.”11 Recall that The Hunted Slaves (1861), by Richard Ansdell, illustrates how a man’s physical build could symbolize not only his abilities but also his masculine commitment to protect and defend his loved ones (see fig. 1). The painting depicts a muscular man stripped to his waist, defending his wife from dogs set upon them by enslavers as they flee through a field.12 Half of the painting is taken up by the bodies of the three large dogs as they snarl at the couple. The man shields the woman with his body. Broken manacles indicate his strength and physical resistance to slavery. His bright red sash stands out among tones of brown in the painting. Encircling his waist and dangling between his legs, it highlights his masculinized and sexualized strength and power. His feet are planted firmly in a wide stance, and his gaze is directed fearlessly at the open mouth of one of the mastiffs. He wields an ax above his head. One of the dogs lies in the foreground on his back, apparently incapacitated by the man.

As the culture saw erotic possibilities and beauty in black bodies, skin tone was also noted in addition to musculature. The presence of antebellum “fetish” markets of light-skinned enslaved women, in particular, has been documented by scholars. Edward Baptist, for example, argues that the antebellum domestic slave trade might be reconsidered as a “complex of inseparable fetishisms,” given the slave traders’ “frequent discussions of the rape of light-skinned enslaved women, or ‘fancy maids,’” and “their own relentlessly sexualized vision of the trade.”13

Although we have little evidence for a formalized sexual fetish market in black male flesh, historical scholarship shows us that light-skinned black men were eroticized and appear with regularity in documented examples of intimacy with white women. Baptist’s conclusion that “light-skinned and mulatto women symbolized for traders and planters the claimed right to coerce all women of African descent” can be applied in some measure to light-skinned enslaved men.14 The evidence leads us to speculate that an unusual interest in light- skinned men may have paralleled the more formalized and documented “fetish” market in “fancy maids.” In the antebellum divorce case of one white Virginia couple, Dorothea and Lewis Bourne, Dorothea’s chosen lover, an enslaved man named Edmond, is described in the records by more than one neighbor as “so bright in his colour, a stranger would take him for a white man.”15 Similarly, Eliza Potter’s description of life in New Orleans included a “series of anecdotes that include descriptions of consensual relationships between white women and mixed-race men across state lines.”16 Similar descriptions can also be found in testimony presented to the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission (AFIC), which was established by the secretary of war in 1863 to document the conditions of those freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. White abolitionist Richard J. Hinton, for example, testified that “I have never yet found a bright looking colored man … who has not told me of instances where he has been compelled, either by his mistress, or by white women of the same class, to have connection with them.”17 In another case, a man testified that a man who had been “brought up in the family” was coerced into sex by his mistress, his family connection suggesting that he also was light-skinned.18

We have some evidence of more explicit discourse that points to special sexualization of light-skinned black men. One testimony to the AFIC included a reference to light-skinned men as “fine looking.”19 One man told the AFIC: “It was an extremely common thing among all the handsome mulattoes at the South to have connection with the white women.”20 The association of being light-skinned with being attractive, “fine,” “bright,” and “handsome” suggests a unique assessment for these men. And while light skin may have been viewed as more attractive than dark skin on men, it could not protect them from sexual violations; indeed, it may have only added another dimension to their exploitation. In patriarchal society, the sexual abuse of “nearly white” men could enable white women to enact radical fantasies of domination over a man with the knowledge that their victim’s body was legally black and enslaved, subject to the women’s control.

The disjunction between the images of sexualized vigor that circulated especially among abolitionists and the realities of enslaved men’s physical health underscores how enslaved men’s bodies served important cultural as well as social aims. Because we are still living with a legacy of slavery that established black men’s bodies as uniquely powerful and sexually potent, it is important not to overlay twenty-first-century images of muscular athleticism on enslaved men. First, we should keep in mind that standards change over time. The idealized body of today is not the ideal of previous generations (including recent ones), even for athletic bodies. Second, the diet of enslaved men was such that many men’s musculature would have been retarded or disproportionate from repetitive work. Bones would have been weakened from calcium deficiencies. One man who had been enslaved in South Carolina explained how little they received to eat: “The time of killing hogs is the negroes’ feast, as it is the only time that the negroes can get meat, for they are then allowed the chitterlings and feet; then they do not see any more till next hog-killing time. Their food is a dry peck of corn that they have to grind at the hand-mill after a hard day’s work, and a pint of salt, which they receive every week. They are only allowed to eat twice a-day.”21 Similarly, another man discussed his experiences in Georgia and how much work was required on very little food: “[The owner] would make his slaves work on one meal a day, until quite night, and after supper, set them to burn brush or to spin cotton.” He continued: “Our allowance of food was one peck of corn a week to each full-grown slave. We never had meat of any kind, and our usual drink was water.”22 The classically developed muscular bodies depicted in many abolitionist accounts would not have been possible on many an enslaved man’s diet and workload.

In addition to being malnourished, many enslaved men were also vulnerable to disease. As Larry E. Hudson notes, some enslaved people would have been “frequent visitors to the sick house and generally unable to function at best.”23 One man, for example, a field hand named Frederick, was “covered with ulcers” and “rotten.” He died before he was fifty.24 Runaway notices include descriptors such as “bowlegged” and “bandy-legged,” a condition that was probably caused by poor diet.25 Those enslaved by James Henry Hammond were “extraordinarily unhealthy” because of the diet and treatment that were part of life on his plantation.26 Masters, Faust explains, provided only what was “minimally necessary for [slaves’] maintenance as effective laborers.” The standard diet supplied “inadequate amounts of calcium, magnesium, protein, iron, and vitamins.” Venereal disease was not uncommon. In addition to disease, men’s bodies were more often subjected to debilitating injuries. Three times as many men as women also suffered from fatal accidents.27

While the objectification of enslaved men’s bodies could appear to some as a harmless appreciation for the beauty of some enslaved men, overall the same impulses that gave rise to eroticizing enslaved men’s bodies fueled the forces of enslavement that were held in place by physical abuses and exploitations. Retur...