![]()

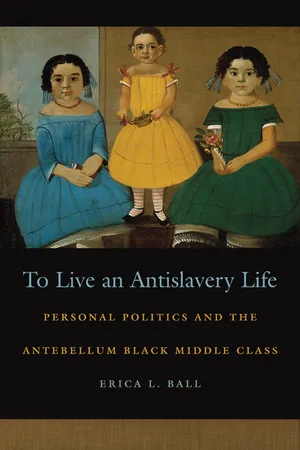

TO LIVE AN ANTISLAVERY LIFE

Personal Politics and the Antebellum Black Middle Class

ERICA L. BALL

![]()

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE

African American Advice Literature and Black Middle-Class Self-Fashioning

CHAPTER TWO

Slave Narratives and the Black Self-Made Man

CHAPTER THREE

Antislavery Discourse and the African American Family

CHAPTER FOUR

Domestic Literature and the Antislavery Household

CHAPTER FIVE

Transnationalism, Revolution, and the Anglo-African Magazine on the Eve of the Civil War

EPILOGUE

Notes

Index

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have had the good fortune to receive assistance from a number of institutions and individuals over the many years that I have worked on this project. Although it is impossible to fully convey just how much their support has meant to me, I am thrilled to have this opportunity to finally thank them properly.

At the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, I received the best possible introduction to academic culture. Carol Berkin, Ann Fabian, Kathleen McCarthy, David Nasaw, and my wonderful advisor, Colin Palmer, all offered thoughtful and constructive advice on the dissertation, helped me to secure generous fellowships, including a Minority Access/Graduate Networking President’s Dissertation Year Fellowship, and served as model mentors as I progressed through the various phases of graduate study. Members of my CUNY cohort, meanwhile, made the process a genuine pleasure. Collegial, generous, filled with boundless intellectual zeal and good humor, and always ready for late-night bowling and karaoke, Megan Elias, Kathleen Feeley, Terence Kissack, Cindy Lobel, Delia Mellis, and Peter Vellon all read portions of this manuscript in its various forms, invariably offering unselfish advice and candid criticism.

During my time as a faculty member in the history department at Union College I had the privilege of enjoying the fellowship and camaraderie of some terrific colleagues. I am especially grateful for the friendship and encouragement of Ed Pavlic and Stacey Barnum, Charles Batson, Deidre Hill Butler, Lorraine Morales Cox, John Cramsie, Andy Feffer, Richard Fox, Melinda Lawson, Joyce Madancy, Teresa Meade, and Andy Morris.

Librarians and staff at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Schaffer Library, and the Pollak Library assisted with the research for this project, going out of their way to oblige my numerous ILL requests and to track down documents. California State University, Fullerton, facilitated the completion of this project by providing me with several H&SS Faculty Summer Research and Writing Grants, a Junior Faculty Summer Stipend, and a Faculty Development Center Track Grant. CSUF American Studies Department administrators Carole Angus and Karla Arellano made book orders and travel a breeze.

The editors at the University of Georgia press have been fantastic. Project editor John Joerschke and copyeditor Ellen D. Goldlust-Gingrich have been a pleasure to work with. They whipped the book into shape and saved me from making some embarrassing errors. Acquisitions editor Derek Krissoff, in particular, remained enthusiastic about the project over the years and exhibited extraordinary patience as I slowly moved toward the finish line. I am also grateful to the two anonymous readers who reviewed the book in manuscript form, offering detailed notes and suggestions on how to tighten and pull together the threads of the narrative. Their input has improved the book immeasurably.

The book also benefitted greatly from the thoughtful questions I received from chairs, commentators, and audience members at several academic conferences. I would especially like to thank Elsa Barkley Brown, John Bezís-Selfa, Darlene Clark Hine, Graham Hodges, Kate Masur, W. Caleb McDaniel, Richard Newman, Manisha Sinha, James Brewer Stewart, and Julie Winch. Although they did not all necessarily agree with my interpretations, their insightful observations helped me to refine my ideas and sharpen my arguments and take into account possibilities I otherwise might not have considered.

It is impossible to say what a delight it is to be a part of the extraordinary Cal State Fullerton community, where I now make my home. I am daily inspired by our students and filled with admiration for our faculty: men and women who approach scholarship and teaching with extraordinary passion and enthusiasm, even in the face of staggering budget cuts and uncertainty about what the future holds for public education. My colleagues in the CSUF American Studies Department—Allan Axelrad, Jesse Battan, Adam Golub, Wayne Hobson, John Ibson, Carrie Lane, Elaine Lewinnek, Karen Lystra, Mike Steiner, Terri Snyder, and Pam Steinle—have created an environment that feels more like a family than a place of employment. I continue to be amazed that I have had the good fortune to find myself in such an intellectually vibrant and warm community. I would especially like to thank Leila “Scissors” Zenderland and my colleagues Stephen J. Mexal and Benjamin Cawthra for helping me to get “unstuck” at critical moments in the writing process.

Finally, I owe a number of debts that can never be repaid. Claire Potter, my undergraduate advisor at Wesleyan University, served as my very first model for the academic life and encouraged me to pursue graduate study. My dissertation advisor, Colin Palmer, gave me the best advice: no matter how people respond to your work, always “own” your ideas. My parents, Eugene and Carolyn Ball, taught me to love history, music, and literature and to value education. They also, along with my sister Stephanie, maintained their good humor despite having to answer countless questions from friends curious about the status of “Erica’s book.” Ultimately, however, I owe the greatest debt to Brian Michael Norton. He has read nearly every version of this project—from drafts of the dissertation proposal to the final proofs—over the past decade. He is, and always will be, my best everything: friend, editor, collaborator, critic, partnerin-crime. Together with our dog Abby, every day feels like a joyous adventure, and I can’t wait to see where we go next.

My grandparents, to whom this book is dedicated, would be surprised, I suspect, to learn that their granddaughter had written a book about many of their most cherished ideals. Although they are not here to see the final product, I hope that they would be pleased with the result.

![]()

Introduction

By the 1830s and 1840s, a small but noticeable number of free African Americans living in the North had received the education and training necessary to take up positions as teachers, ministers, and newspaper editors; a few had even achieved some measure of financial success as entrepreneurs and small-business owners.1 Aware of their anomalous and precarious status as free blacks in a slaveholding republic, they created a print culture to promote a spirit of racial consciousness, to provide their communities with information on the news of the day, and to offer African American readers advice on a range of personal and domestic concerns.2

Because much of this discourse centered on middle-class personal and domestic conduct and consisted of calls for education, morality, temperance, and economy, historians have generally characterized these efforts as evidence of “racial uplift ideology,” the discursive part of a larger campaign to redirect a phenomenon historian Patrick Rael defines as “racial synecdoche”: the white American tendency to highlight the “misdeeds of the few” African Americans who “were thought to have affronted public morality” and then to characterize those behaviors as innate racial traits and thus justification for continued antiblack discrimination and enslavement.3 Scholars argue that elite African Americans hoped that this process of racial synecdoche could be redirected and that a class of “elevated”—in other words, frugal, virtuous, well-educated, and well-mannered—African Americans could engage in an antebellum version of the “politics of respectability” and serve as examples proving the worth of the entire black population, undercutting the racism of the day, and bolstering the campaign for the abolition of slavery and the acquisition of citizenship rights.4 As scholars have also shown, the desire for “elevation” and “respectability” remained bound up in the development of northern black institutional life, political consciousness, and antislavery ideology and activism.5

This scholarship has done much to reveal the centrality of discourses of respectability to antebellum black protest thought and activism but has not fully explored such discourses’ impact on the ethos and culture of the emerging black middle class.6 Building on the work of scholars who see class formation as a cultural as well as economic process, this book focuses on the literature directed toward elite and “aspiring” northern African American readers in the three decades preceding the Civil War.7 Across a variety of genres—including convention proceedings, letters, personal narratives, didactic essays, humorous stories, and sentimental vignettes—a generation of northern black writers, activists, and intellectuals crafted a set of black middle-class ideals, simultaneously respectable and subversive, that fused advice on personal and domestic conduct with antislavery and transnational revolutionary themes. Repeatedly insisting that northern free blacks internalize their political principles and interpret all their personal ambitions, private familial roles, and domestic responsibilities in light of the freedom struggle, African Americans such as Susan Paul, Frederick Douglass, and Martin Delany offered virtuous political models and exemplary figures for elite and aspiring northern black readers to emulate. This rhetoric amounted to far more than endorsements of the “politics of respectability.” Rather, African American writers urged elite and aspiring African Americans to engage in a deeply personal politics by fashioning themselves into ideal husbands and wives, mothers and fathers, self-made men and transnational freedom fighters and by committing themselves to living what former slave turned Congregationalist minister Samuel Ringgold Ward would call “an anti-slavery life.”8 In the process, they began crafting a form of personal politics especially for elite and aspiring African American readers that ultimately defined the worldview of the emerging black middle class.9

The first chapter of To Live an Antislavery Life begins by exploring the various arguments that linked key forms of middle-class self-fashioning with the charge to live an antislavery life. By analyzing black conduct discourse—advice specifically directed to the courting sons and daughters and the young husbands and wives of the emerging northern black middle class—we will see that black conduct writers framed popular middle-class arguments about self-improvement as integral to a larger process of personal transformation. For these men and women, the personal conduct and behavior associated with middle-class forms of respectability constituted far more than a narrow political strategy or a public political performance. Rather, the processes of self-fashioning associated with respectability were deemed crucial to the personal transformations required to become independent, virtuous, ideal men and women and therefore embodiments of antislavery sensibilitie...