![]()

1

Separate Worlds

Spain and the American Southeast in the Sixteenth Century

What visitor to the forests of the southeastern United States has not imagined the native people who used to inhabit this landscape? In a southeastern forest in the 1700s one might have seen a mysterious Creek or Cherokee walking silently in the gloom of an old-growth forest, dressed in a breechcloth, buckskin moccasins, a cloth hunting shirt, a brightly colored cloth turban, and armed to the teeth with a steel tomahawk, a razor-sharp scalping knife, and a flintlock rifle.

But a full two centuries earlier than the time when such a Creek or Cherokee might have been seen, there were two sets of even more mysterious people who collided with each other in the vast forests that blanketed the Southeast. In the 1500s Spanish adventurers explored the interior of the Southeast and made first contact with many of the native chiefdoms that dominated the region. These Spaniards were more medieval than modern. They were fighting men who wore body armor and fought with crude matchlock guns, crossbows, lances, and even more with steel swords. Above all they regarded themselves as Christians who were pitted in a great struggle against infidels and devil-worshippers everywhere, both at home and abroad.

The native chiefdoms these Spaniards encountered in the Southeast also fielded fighting men, with a centuries-old military tradition of their own. The chiefdoms to which they belonged were dominated by chiefs who claimed descent from the gods of their universe, and most particularly from the Sun. These chiefs had power over people who made their living by hunting, fishing, and gathering wild food, but what they relied upon even more was farming. When they went to war they preferred to fight almost naked. A Southeastern warrior wore a breechcloth and moccasins of brain-tanned deerskin. He wore leggings when traveling in the woods, and he wrapped a mulberry cloth, deerskin, or fur mantle about his body when the weather was cold. He was adept with the bow and arrow, but his principal martial weapon was the war club, his weapon of choice in hand-to-hand combat.

These chiefdoms were largely self-sufficient, and the people were greatly circumscribed in their knowledge of the larger world. Frequently a chiefdom found itself at war with one or more neighboring chiefdoms, and because of this the members of such a chiefdom could not have traveled widely or inquired into the larger world even if they had wanted to. The chiefdoms of the Southeast were small, intricately structured, self-contained worlds, whose members would have found our imagined eighteenth-century Creek or Cherokee hunter almost as alien as they found the Spaniards who appeared so rudely in their midst in the sixteenth century.

The first sustained encounter between the separate worlds of Europeans and the native people of the southeastern United States occurred in the middle years of the sixteenth century. Between 1539 and 1343 Hernando de Soto led a small army to explore a vast area of the continent. The principal motive that impelled De Soto and his followers was the possibility of discovering a rich, populous society, like that of the Aztecs or Incas. When judged in terms of how well he achieved his objectives, De Soto’s expedition was a colossal failure. But along with Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s simultaneous exploration of the southwestern United States, De Soto’s exploration of the Southeast was one of the most important historical events in sixteenth-century America. Members of his expedition traveled thousands of miles through about a quarter of the present territory of the United States, a vast portion of the continent, and they visited a large number of native societies, most of whom had had no previous firsthand experience with Europeans.

But for all this, the De Soto expedition has won only a small place in American history. Everyone knows that De Soto discovered the Mississippi River, and that he later died on the banks of that river and was buried in its waters. An automobile was named after him. His name dots the southern landscape, attached to towns, bridges, waterfalls, caverns, pecan houses, and so on. But where did his expedition go? What sort of people did it encounter? And how did it affect these native people?

It is easy to speak of the De Soto expedition as an instance of “first contact” between the Old World and the New. But this is at best a lazy and imprecise characterization. The Indian chiefdoms De Soto encountered did not think of themselves as a collectivity. They were first and foremost Apalachees, or Coosas, or Chicazas. And since they had no knowledge of Europe, Africa, and Asia they surely did not think of themselves as constituting a New World. They were parochial to a degree that few modern people can imagine. Moreover, there is little evidence that De Soto and his men thought of themselves as emissaries from the Old World. They had nothing so grand in mind. They spoke of themselves as Christians, but more fundamentally they were entrepreneurs and adventurers. They were officially charged with evangelizing the Indians, but even more they hoped to acquire wealth, power, and social honor.

“Spaniards”

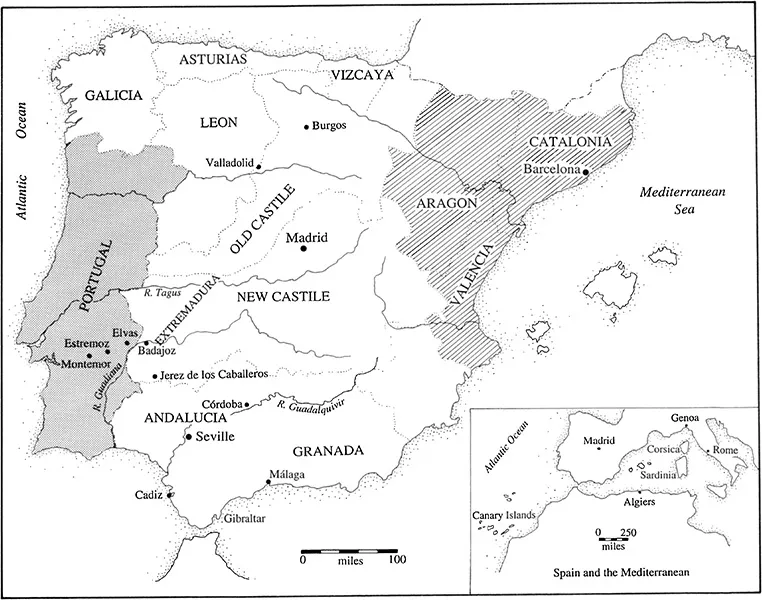

Referring to De Soto and his men as “Spaniards” is little more than a convenience.1 In fact, it is historically inaccurate. In 1539-43 the polities to which De Soto and his men owed their allegiance were not modern nation states, and De Soto and his fellows were not modern people. The Iberian peninsula as a geographical entity (map 1) had been referred to as Hispania throughout the Middle Ages, and as time went on the people of the Iberian peninsula had a growing sense of being a people as opposed to, say, Frenchmen or Englishmen. Their primary social identification was to their town or region, and they identified only weakly with one of three Christian crowns: Castile, Aragon, or Portugal.

In 1469, with the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon to Isabela of Castile, two of these crowns were joined together. Their long reign set in motion a remarkable cultural florescence, and for some decades Spain became the greatest power in Europe.2 During their reign, Spain succeeded in two stupendous achievements that reverberated in world history for centuries. One was that in 1492 Ferdinand and Isabela completed the centuries-long reconquest of their land from the Muslims, who had invaded in 711 and had overrun the Iberian peninsula in a humiliating conquest. The second achievement, in that same miraculous year, was that Ferdinand and Isabela backed Columbus’s discovery of the New World and initiated the conquest and settlement of that vast unknown land.

Map 1. Spain in the sixteenth century. The kingdom of Aragon in eastern Spain is hachured; the kingdom of Castile, including navarre and the basque Provinces, is left blank.

The royal houses of Castile and Aragon were linked together by marriage, but the two kingdoms were not effectively joined together. They remained politically distinct patrimonies and their economies were not integrated with each other. Their political histories were different and they were unequal. Castile was larger and more populous than Aragon and was therefore dominant. Moreover, their interests were different. Castile looked toward the Atlantic for opportunities, while Aragon looked toward the Mediterranean. With the discovery of the New World, America belonged to Castile, and the inhabitants of the kingdom of Aragon were technically foreigners in this new land. In fact, if Isabela had had her way, only Castilians would have conquered and settled the New World.3

The kingdom of Aragon, comprising the states of Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia, was fundamentally a commercial empire, trading textiles to Africa and Sicily, as well as to other provinces in the Iberian Peninsula. The Aragonese economy was dominated by an emerging bourgeoisie, and their government was a constitutional system with limits on the power of the rulers and with protection against arbitrary power. The Aragonese oath of allegiance to the king was “We who are so good as you swear to you who are no better than we, to accept you as our king and sovereign lord, provided that you observe all of our liberties and laws; but if not, not.”4

The political and economic character of Castile was quite different. The Castilian economy was heavily pastoral, with wool being the principal export, and in Castile the Reconquest was more protracted and bitter than in Aragon, and it shaped the character of the Castilians to a greater degree than it did the Aragonese. The Reconquest was more than a political action. It was a crusade against infidels. And insofar that plunder could be won, it was an avenue to wealth. Huge grants of land reconquered from the Muslims strengthened the hereditary noble class in Castile. Reconquering land and picking up and moving from one place to another went hand in hand, and migration became familiar to Castilians. Moreover, because Castilians conceived of the Reconquest as a religious crusade, the church in Castile became heavily involved in military affairs, and as a consequence, a series of powerful Christian military orders emerged—Calatrava, Alcántara, and most especially Santiago. The latter was named after St. James (i.e., Santiago), the patron saint of Spain, who was believed to have miraculously appeared after great battles were fought. The church and the military were intimately combined in these orders, or brotherhoods, and in time they came to possess vast estates with many vassals. Being admitted to the Order of Santiago was a very high honor. One had to document a “pure” Christian genealogy for three to four generations, and one had, of course, to possess sufficient wealth.

The ideal Castilian hidalgo—“a somebody”—was a man who was never so happy as when he was at war. For such a man, the most esteemed wealth was not to be won by the sweat of his brow, but through booty and land taken in warfare with infidels. Victory was not to be won so much through military technology as through faith, valor, and the exercise of will. The ideal hidalgo was a man who was contemptuous of inherited wealth and a comfortable, settled life. If one had to be tied to property, then let it be sheep, which could be herded from place to place. Moreover, in Castile the bourgeoisie did not grow strong enough to serve as a check against the power of the nobility. Indeed, the power of the Castilian aristocracy made for constant managerial problems for Ferdinand and Isabela.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Aragon was hit hard by a series of epidemic diseases and went into steep population decline. As Aragon’s population fell precipitously, the mercantilist economy shrank. Hence, at the time when Castile found itself master of the Iberian peninsula at the close of the fifteenth century, Aragon found itself unable to provide the skills in banking and overseas trading that Castile needed. Providing these skills fell instead to the Genoese, who quickly became entrepreneurs in Seville, Cadiz, and Cordoba and were important actors in Spain’s rise to world power.5 And so it was that Christopher Columbus, a Genoese, was backed by two Iberian monarchs who, flushed with victory after more than seven centuries of struggle with Muslims, were looking for new infidels to conquer.

The profound political disunity of sixteenth-century Spain was one of the reasons why Christianity was so important. Like nothing else, the idea of the religious crusade mobilized Castilians to risk their lives and to pay taxes. Belief in the Christian mystery was a way of rising above real-world divisions to bind together Castilians, Aragonese, and Catalans. Christianity was so important that Spaniards conceived of Christian ancestry as something one inherited in one’s “blood.” It was Christian blood that made Spaniards different from others. Thus, their concern with limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) was not the racism that came to exist in the nineteenth century, but rather a conception that set Christians apart from people of other religious persuasions, especially Jews. And one purpose of the Spanish Inquisition instituted by Ferdinand and Isabela was to determine whether the conversos—Jews who had been coerced into converting to Christianity—had truly become Christians.6 Thus it was that De Soto’s men thought of themselves collectively not so much as “Spaniards,” but as Christians.

The social structure of Castile and Aragon was strongly hierarchical. At the very top were twenty-five Grandes de España, descendants of the oldest families, whom the king addressed as primo (cousin). These grandees did not remove their hats in his presence. They all knew each other and acted as a group. There were other titled aristocrats—títulos—who possessed somewhat less exalted status.

The next tier in the hierarchy was occupied by the lesser nobility, a class, rather than an organized group. These were caballeros and hidalgos, who might be addressed as Don, and who could be rich or poor. Some were descended from nobles, while others were rich merchants or successful military men. They were exempt from paying taxes to the crown, could not be tortured or sentenced to serve as oarsmen in the galleys, and could not be imprisoned for debt. These advantages made hidalguía highly coveted, and people went to great lengths to achieve this status. Some even risked falsifying their genealogies.

At the bottom of this Castilian hierarchy were the peasants, who constituted about 80 percent of the population. Some were well off, but most of them were extremely poor. To them fell the task of agriculture, and theirs was a backward agricultural system.7

In the sixteenth century the Spanish military was superb. Through experience in the Reconquest, the men of the military were accomplished at laying siege, and they were notable for their ability to endure and overcome the rigors of hunger and hardship. Technically they were not soldiers, because military men were not set apart from civilians in sixteenth-century Spain. Most sixteenth-century Spaniards were skilled at using arms, and even clergy were capable of wielding arms if need be. Those who went to the New World to improve their fortunes were not paid salaries; instead, they expected to be given a share in the conquest. They were compañeros (partners, or companions) in the enterprise. Perhaps because the characteristic military engagements throughout the Reconquest were skirmishes and surprise attacks, Spanish footmen were superb, individualistic fighters.8 And just as the skills of Spanish footmen had been tempered in the crucible of the Reconquest, so had the skills and tactics of Spanish horsemen. The tactical advantage conferred by the horsemen in the conquest of New World peoples can hardly be overstated. When the Inca treasure was divided up among Spanish conquistadores at Cajamarca, horsemen were given twice the share of footmen.9

Much of the legal apparatus employed by Spain in the exploration and conquest of the New World was based upon medieval Iberian institutions that had been modified to meet new circumstances. The preponderance of the military actions against the Moors, for example, had been privately financed, but always with authorization by the crown...