![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Science offers a fascinating career, whether it is working in research in a university or a national or international laboratory, or contributing to the field in the many commercial companies developing innovative new products and services that benefit society.

Wherever you work and whatever your field, you will no doubt be called on from time to time to make a case for your work, to sell your science, perhaps in a grant application or for work for a customer. You may also be asked to create the new science, the new product or the new service that takes the field forward. You probably have more than enough to do in your day job, and putting together the information you need and working out the next steps can seem to be a distraction.

All too often, scientific research is justified by looking backwards to try to work out what the impact was; this is not a luxury that many organizations can enjoy, nor does it really help win support for the next research programme. The thesis of the authors’ work and of this book is that it is much better to plan in advance what the work will achieve, how it will benefit others and how the results will be communicated and used (for the public good or as products that your organization sells). Planning for impact requires ingenuity and inspiration; it often brings new ideas, and is interesting and challenging. It improves the chances of your research making a real difference.

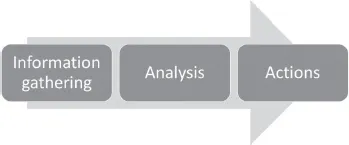

The approach is based on tools from professional marketing, adapted through practical experience for scientific research and development. This book aims to help you gather the information you need and then to analyze it quickly, easily and effectively. It describes a logical sequence of steps, working from the big picture to specific actions, which will ensure that you cover all you need. The first part is concerned with information gathering, next we will use some marketing tools to analyze the data and following that we work out what we will actually do:

It is all about trying to match what your organization does to what your customers want, and communicating with the customers. The tools can, and should, be adapted to your particular organization, but they give a tried-and-tested framework to use.

The last part of the book is some advice, from experience, on how to use the material in the workplace. But really, the book has one simple aim: to pass on what the authors wish they had known earlier in their careers.

![]()

Chapter 2

Information Gathering

In this chapter:

•How to research your market

•How to identify your stakeholders, customers and competitors

2.1Why Is All This Information Needed?

“But it is obvious why this work is so important!” This is how most discussions about the need for scientific research and development begin. It may well be obvious to people working in the field, but it may not be so clear to funding councils, to politicians, to the general public, to senior management or even to colleagues. Perhaps, it is reasonable sometimes for other people to challenge the value of the work (after all, in some cases, they are paying for it).

The response in academic research is often to try to explain how the work will contribute to solving the problems of society — the ‘grand challenges’ of ensuring effective healthcare, energy supply, the new digital economy and ensuring a safe and secure environment. Claiming that research into the measurement of, say, a neutron interaction cross-section, underpins the whole of the nuclear energy industry is a long stretch. Of course, it will make a contribution to the industry, but to be something you can use to help sell your work the link needs to be much clearer.

This section helps you gather the information you will need to make your case more specific. There is another benefit as you will need exactly the same information to write the introduction to scientific papers. The three main questions it will help you answer are:

•What are the specific drivers for the work?

•Why should we (rather than another organization) do the work?

•Who will benefit from it?

To make this very useful for you, there is one strict rule to follow. You need objective evidence for all the information — this could be reports, papers, feedback from customer visits, sales data — otherwise it is just your opinion and this may, or may not, be right.

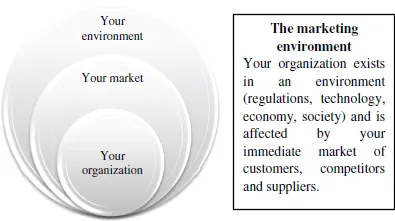

2.2The Marketing Environment

The first step is to gather the information on the external factors that have an impact on your organization, in the short and long term. Big picture issues such as changes in society, changes in regulations and changes in technology may affect your organization in the future much more than may come to mind. Your competitors and customers may have shorter term effects on your organization. All of these factors, in marketing jargon, are called the marketing environment.

So the first step is to gather the information on your marketing environment, starting with the long-term trends.

2.3Gathering Information on the Long-Term Trends

Science is a long-term game. It can take many years before a new instrument or method is adopted — after all — as Sir William Preece said in the quote above, why should any organization invest in something new and expensive unless there is a strong motivation?

The essential first step in analyzing the market is to find out the big picture, the long-term trends that could influence your customers and your organization. This is useful from a business perspective but also from a scientific point of view; any research you do on this will help you write the introductions to scientific papers or presentations. In marketing, this is called PEST analysis, where you structure the analysis to take into account Political, Economic, Social and Technological factors.

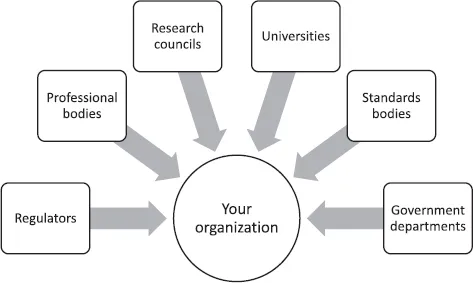

To make PEST analysis more useful in a scientific market, it can help to be more specific by first identifying all groups that could have an influence on or an interest in the field (the stakeholders). Stakeholders typically include:

•Regulatory bodies (such as Health & Safety organizations, environmental protection agencies, pharmaceutical licensing authorities).

•Professional bodies (for example, the Institute of Physics, Royal Society of Chemistry, international societies).

•Government departments.

•Research Funding Councils (such as the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the UK).

•Funding bodies and charitable funding bodies (Innovate UK, Wellcome Trust…).

•Universities.

•International organizations (the World Health Organization, WHO; the International Atomic Energy Agency, IAEA; etc.).

•National and international committees.

•Standards bodies (for example, International Organization for Standardization (ISO)) and national accreditation bodies (organizations that are affiliated to ILAC (the international organization for accreditation bodies), such as UKAS, DAkkS, CoFRAC).

It may also be worth considering direct customers and competitors as stakeholders as well, although we will gather more detailed information on both these groups in more detail in the next sections.

A quick graphical representation (a stakeholder map) can be useful to get an overview of the main organizations or groups that affect your organization:

The trick is to list the specific stakeholders that have an effect on your organization — for example, which particular national committee is responsible for defining the Codes of Practice that your customers will be following in the future? Which government department is responsible for policy in your field? Given this list, the next step is to study how they could influence your market in the long term when considering the following questions:

•What are the changes in science and technology that could change your field?

•What are the economic changes (how will funding change)?

•What are the likely changes in laws, regulations, standards or professional good practice guides?

•Are there any changes in society or politics that could be important?

There are many different sources of information you can consult. For changes in science and technology, scientific conferences are a useful source of information, but take the time to visit the industrial exhibition as well as listening to the presentations. Publications by the stakeholders, such as review articles and trade journals will also give you some insights. International organizations, national organizations and professional bodies often publish very thoro...