- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With All Your Mind makes a compelling case for the value of thinking deeply about education in America from a historically orthodox and broadly ecumenical Christian point of view. Few people dispute that education in America is in a state of crisis. But not many have posed workable solutions to this serious problem. Michael Peterson contends that thinking philosophically about education is our only hope for meaningful progress. In this refreshing book, he invites all who are concerned about education in America to "participate" in his study, which analyzes representative theories and practical strategies that reveal the power of Christian ideas in this vital area.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access With All Your Mind by Michael L. Peterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Education Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

What Is Philosophy of Education?

On one occasion Aristotle was asked how much educated people were superior to those uneducated: “As much,” he replied, “as the living are to the dead.”1 The words of the great teacher remind us of the incredible power of education. All persons, of course, have value and worth regardless of their level of education. But Aristotle’s point is that proper education enlivens the mind and shapes the whole person.

Most people in the United States spend at least twelve years of their lives in formal education, and most in other Western countries spend at least eleven years. Many extend their education through college or beyond. The enormous time and energy devoted to education justify careful consideration of its nature and purpose. In the words of Abraham Lincoln, the discussion of education is “the most important subject which we, as a people, can be engaged in.”2

When we consider education, all sorts of important questions immediately arise: What form should education take? How should education interact with culture? Can morals and values be taught? What is the knowledge most worth having? What relationship should education have to gainful employment? What impact does religious faith have on learning? What impact does learning have on faith? Working through such questions and arriving at clear and consistent answers puts us in the best position to guide the education of our young.

WHY STUDY THEORY?

The most significant questions concerning education are theoretical, not practical. They pertain to how we think in broad terms about education. At the level of theory, we contemplate education in terms of its aims and goals and ideals. Discussions of these matters depend on even more fundamental debates over what the human being is that we are trying to educate, on what truth is, and on what capabilities people have for knowing it. These are abstract and complicated subjects calling for deep thought and reflection.

Yet our culture does not encourage us to be reflective. We are typically more concerned with actions and results than with theory: we are more interested in “how” rather than “why.” This obsession with practice has been detrimental to the educational enterprise. Charles Silberman claims that our educational milieu suffers from “mindlessness,” charging that it uncritically prizes technique over understanding and elevates methodology over well-defined goals.3 Modern educators have been so busy devising new instruments for measuring intelligence, exploring effective strategies for teaching computer skills to elementary school children, and offering more efficient ways to complete a college degree that they have seldom stopped to ask why such things are desirable.

Few practicing educators in Western culture address the larger meaning of education. According to Lawrence Cremin, this is painfully true in the United States:

Too few educational leaders in the United States are genuinely preoccupied with educational issues because they have no clear ideas about education. And if we look at the way these leaders have been recruited and trained, there is little that would lead us to expect otherwise. They have too often been managers, facilitators, politicians in the narrowest sense. They have been concerned with building buildings, balancing budgets, and pacifying parents, but they have not been prepared to spark a great public dialogue about the ends and means of education. And in the absence of such dialogue, large segments of the public have had, at best, a limited understanding of the ways and wherefores of popular schooling.4

Clearly, many teachers do a good job of teaching. Perhaps they do so instinctively, without really pondering aims of education. But they would greatly enhance their contribution as educators by deliberate reflection on educational theory. Although suggestions occasionally surface about nurturing our educators in the great literature of education, we should pay much more attention to this need. Astoundingly, the business of education continues at a rapid pace without educators or the general populace having clear answers to the most basic questions: What is the purpose of education? What goals do new techniques and methods serve? What kind of person is our educational system supposed to produce? These are theoretical questions that force us to articulate and evaluate our basic commitments.

Our fixation on educational methodology and avoidance of vigorous, open discussion of educational theory has led over time to our unconscious or at least uncritical acceptance of unworthy and confused ideals. Unless we squarely face the tough, foundational questions, we can never get solid answers, and without reliable answers education in America is vulnerable to political and cultural pressures. To be sure, education will always serve some ideals. We must make sure that its ideals are worthy.

Borrowing religious terminology, Neil Postman writes that education inevitably serves various “gods.” A god in this sense is a comprehensive story or “narrative” that has sufficient complexity and symbolic power to attract us to organize our lives around it. A great narrative constructs ideals, prescribes rules of conduct, and provides a sense of purpose; it tells us what the universe is like and how to understand our place in it.5 “Where there is no vision,” Proverbs tells us, “the people perish.”6 This is true in all areas of life, and it is true in education. Education requires some organizing principle, some dominant vision to give meaning and direction to its pursuit.

The history of education, like the history of civilization itself, contains the record of many gods that failed, many narratives that were not ultimately satisfying. There was once the narrative of the Protestant work ethic, which assured people that hard work and self-denial were sure ways to secure God’s favor. In its name, children were educated to avoid idleness and develop self-discipline. There was also the great god of Communism, which promised equal distribution of wealth in a classless society. Under this god, education was to serve the state’s ultimate purposes. Obviously, there are many other gods. Some have been discarded on the ash heap of history while others still have their following. A god still in vogue is consumerism, whose story tells us that we are what we possess and that our identity is defined by what we do for a living. Education in service to this god turns out productive economic units that keep the economy growing.

But all of these gods are false ultimates, and education fashioned in the image of a false god is misguided education. What other gods or ideals are being served in our day? In the future, will we also look back on them as failures, untenable ultimates? Wise answers to these questions will come only through our close attention to educational theory.

We need to recover the normal link between educational theory and practice. Theory guides practice by establishing the aims of education and projecting basic ways in which these ends can be reached. To paraphrase Kant, practice without theory is blind. Without theory, responses to problems are arbitrary, shortsighted, and susceptible to hidden agendas. Concrete decisions—about whether to distribute condoms in high schools, whether to add distance learning over the Internet to a college curriculum, and a host of other matters—should stem from a coherent theoretical framework.

Obviously, education is a topic about which responsible people disagree, but unless we engage in reasonable dialogue, there is little hope for salvaging, let alone improving, our rapidly deteriorating public educational system. Where should we start? We cannot make initial progress by debating the conduct of education: curriculum offerings, pedagogical methods, sex education in the lower grades, and other such matters. All such practical strategies and techniques inevitably reflect more abstract goals and objectives. Our differences about the goals of education predictably cause disagreements about practical strategies and techniques, whereas consensus on goals would allow meaningful agreement regarding practice.

Educational goals and objectives, in turn, arise from still more basic philosophical commitments. So, our deliberations must ultimately be rooted in ideas about the nature of reality, knowledge, and humanity itself. This is why it is urgent that we become aware of the various underlying philosophical concepts that shape educational discussions and become skillful in evaluating them. Thus, in the final analysis, no educational practice can proceed intelligently without theory. Every policy and every method, whether we realize it or not, is laden with some concept of what education is all about, and this concept arises from some fundamental philosophical viewpoint. If we seek the broadest possible perspective on education and want to understand the root of so many educational controversies, we must start at the most general, foundational level and work our way to more specific issues. Nothing could be more practical than considering theory first.

Practice has a reciprocal impact on theory. Practice can “test” a theory; it can validate or invalidate educational policies and proposals. A fine-sounding theory may run into difficulties in application and thus cause us to rethink, modify or relinquish our original ideas. Every educational theory has to encounter the hard realities of ordinary life and stand or fall according to its adequacy to human experience. So, there is a proper time for debating the effectiveness and legitimacy of the practical and technical aspects of education. To extend our earlier paraphrase of Kant, theory without practice is empty.

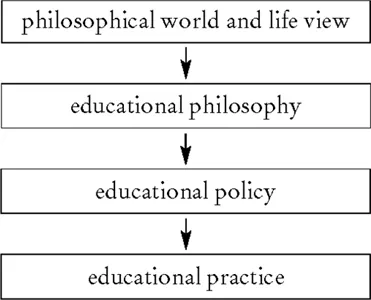

There is a hierarchy to our ideas, from the most abstract and general to the most concrete. Educational policy and practice are logically subordinate to and dependent upon educational theory, and educational theory itself is subordinate to and dependent upon a larger worldview. These relationships are graphically illustrated in figure 1.

FIGURE 1

As a rule, the positions one holds concerning issues at lower levels are derived from the higher levels. An educational philosophy affects policy and practice either by generating a specific conclusion or by providing a general way of thinking. So, no educational decisions can have clear direction without reference to some educational philosophy or theory. Furthermore, no educational theory can have a firm basis without an even more general philosophical perspective.

This hierarchical understanding applies to all educational issues. Take, for example, the practice of nondiscrimination in hiring teachers and in dealing with students. This action arises from a general policy that discrimination is wrong. But the reasons why it is wrong may vary according to one’s educational philosophy. At the level of educational philosophy, discrimination might be viewed as wrong because it violates the inherent dignity of human beings. This belief in their inherent dignity is likewise anchored in an overall worldview, such as a theistic worldview, which understands persons to be created by a personal deity. Of course, the same practical policy of nondiscrimination could also be rooted in a quite different, non-theistic educational philosophy. Many versions of naturalism consider human beings as political entities in competition for power. A corollary of this may be the belief that in education we should level the playing field in the ongoing power struggle.

At this point we have reached the most universal level of discussion in all educational matters—the level of worldview commitments. The more concrete educational strategies and techniques we employ are necessitated or ruled out or at least made optional within the context of a larger worldview. When we become aware of these conceptual relationships, we are then prepared to be discerning and prudent in our deliberations about educational matters. This preparation requires that we acquaint ourselves with the field of philosophy.

PHILOSOPHY AND EDUCATIONAL THEORY

The term “philosophy” can be used to designate either an inherent tendency in human beings or an academic discipline. Literally, “philosophy” means “the love of wisdom.” Human beings have the innate desire to increase their understanding of the world and to find wisdom. Some have the desire more strongly than others, but this desire can be tutored, developed, and refined by an organized course of study. The discipline of philosophy is important, then, because the human quest for wisdom is so important.

The philosophical enterprise is concerned with the analysis and evaluation of beliefs about life’s most important questions: the conditions of knowledge, the nature of morality, the structure of society, the existence of God, the meaning of the human venture, and many more. In addition, philosophy sometimes involves the attempt to assemble a set of answers and insights related to such questions into a coherent system of thought known as a “worldview.” A worldview provides a total, comprehensive way of looking at everything—knowledge, ethics, humanity, meaning, and even the divine.

Although there are numerous ways of packaging philosophical content into academic courses, one way is to designate relatively discrete “departments” of philosophical inquiry, such as philosophy of science, philosophy of art, philosophy of law, and the like. The various “departmental philosophies,” as they are often labeled, investigate the philosophical foundations of specific disciplines, recognizing that these deep commitments shape our thinking about each area. Predictably, thinkers who disagree on fundamental philosophical matters disagree over issues arising within the specific branches of knowledge.

Philosophy of education is one of the many departmental philosophies. It may be defined broadly as the attempt to bring the insights and methods of philosophy to bear on the educational enterprise. Since the philosophical orientation one adopts about the nature of reality, knowledge, and value shapes how one thinks about the nature and purpose of education, philosophy is indispensable to the process of education.

Who can benefit from exploring the philosophy of education? Professional educators, both present and future, teachers, counselors, administrators, and curriculum specialists all need to think carefully about the large philosophical questions that are logically prior to any goals and methods they adopt. Those who are not professional educators—parents, students, legislators, and everyone who recognizes the vital importance of education—will also profit from the philosophy of education.

The example of education simply proves the general need for a guiding conceptual framework in all areas of life and thought. Studying philosophical themes relevant to education offers some people their first opportunity to consider life’s great questions and to form their own viewpoints. When we develop our own philosophical outlook, we are then in a position to formulate meaningful educational and career goals. Indeed, from our worldview we draw impetus and motivation for our own study and achievement. The philosophy of education is important because it allows both professionals and non-professionals to survey the major philosophies of life and think through a host of significant interconnected issues.

CHRISTIANITY AND EDUCATION

Philosophy of education is an extremely valuable subject for Christians. Contemporary Christians feel an obligation to respond to a multitude of educational issues, from the moral deterioration of our public schools to the creation-evolution controversy in science classes. Many people struggle with the decision of whether to attend or encourage their children to attend a private school, perhaps a Christian school. Some seriously consider the question of home schooling. Other Christians are interested in finding the most effective way to navigate in secular educational settings. These pressing challenges call for more than simplistic answers. We need a whole way of thinking about education—that is, a philosophical outlook that relates religious commitment to educational concerns. Out of this understanding, we can intelligently address whatever educational problems we face.

The main point of contact between educational philosophy and Christianity is their mutual attention to the same basic conceptual questions. These are deep questions about the nature of ultimate reality, the process of gaining knowledge, the demands of morality, and the meaning of life. A complete, systematic set of answers to basic philosophical questions constitutes a worldview, and there is a wide range of competing worldviews, all with their distinctive implications for education. The purpose of this study is to articulate a viable understanding of a Christian worldview, put it in interaction with other worldviews, and show how it provides a more helpful framework for thinking about e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One What Is Philosophy of Education?

- Chapter Two Traditional Philosophies of Education

- Chapter Three Contemporary Philosophies of Education

- Chapter Four Toward a Christian Perspective on Education

- Chapter Five Issues in Educational Theory

- Chapter Six Issues in Educational Practice

- Chapter Seven Christianity and the Pursuit of Excellence

- Notes

- Suggested Reading

- Index