![]()

PART

ONE IN THE BEGINNING THERE WERE ONLY FORAGERS in West Central Africa. They lived in small nomadic communities whose members communicated and intermarried with individuals from the outside but they did not develop any social aggregate larger than the community itself. Some time after 500 BCE, a few communities began to adopt a series of technological innovations which allowed them at first to expand the range of gathered foods that were edible and later to produce food rather than just gather it by practicing agriculture and/or the herding of domestic animals. This allowed them to aggregate in larger settlements and to become sedentary wherever farming made this possible. These new communities, sedentary or pastoral, were considerably larger than the foraging households had been and their members began to create new overarching institutions to bridge the social divide that existed between the different local communities. Such institutions allowed them to better cooperate with each other in some economic or social endeavors where this was advantageous to all of them. Such practices of common governance created genuine societies, that is, social aggregates larger than a seasonally unstable set of local households. By the ninth century CE or SO, small societies were becoming the norm which opened the way to processes by which governance could become gradually more intricate and the scale of society could gradually increase to the situations described by outside observers from the sixteenth century onward.

Part One deals with the period from about 400 BCE to 900 CE, during which the basic innovations were adopted that made all the rest possible. It is divided into two chapters. The first one tells of the introduction of ceramics, horticulture, and the early use of metals over nearly a millennium before 500 CE, whereas the following chapter deals with the transformations wrought during the four following centuries by the introduction of cereal crops, a more intensive use of iron tools, large herds of cattle, corporate matrilineages, and dispersed matriclans.

![]()

1

PRELUDES

W

HEN THE EARLIEST SIGNS OF A SET OF NEW TECHnologies that would lead to the creation of larger and more complex societies appeared during the second half of the last millennium

BCE, small communities of foragers were roaming the savannas, woodlands, and steppes of West Central Africa south of the rain forests just as they had done since times immemorial. The first harbingers of change were the adoption of ceramics, accompanied or followed by that of horticulture and husbandry of small domestic stock. The use and fabrication of metal objects followed half a millennium later. Compared with the pace of change in earlier times, these innovations were abrupt, even if they unfolded over some thirty generations, that is, over three-quarters of a millennium. Indeed, at least in part of the area all three developments may well have occurred within a single lifetime.

1 Abrupt or not, the changes were radical. For they concerned something essential: the preparation of food and its availability in a way which made its supply more reliable and eventually more abundant. They also allowed communities which grew crops to become sedentary and in the fullness of time they fostered population growth and its aggregation into larger societies.

None of these technologies were invented by the inhabitants of the area. All were demonstrably introduced from elsewhere, which makes one wonder whether they were carried there by foreign immigrants. One suspects this all the more so because the Njila set of Bantu languages began to diffuse into the area from the earlier part of this period onward. Proto-Njila speakers produced pottery, practiced horticulture, and kept goats. It would seem logical to attribute the spread of these innovations as well as the later spread of metallurgy to their expansion. But the matter is not that simple. At least in the southernmost part of the area and well before the first Njila speakers ever arrived there, foragers did adopt ceramics and the herding of sheep from other foragers who spoke languages related to theirs.2 Could foragers then not have borrowed from other foragers elsewhere in the area as well without any immigration at all? We probably will never know for certain because archaeological sites do not disclose which language was spoken by those who once lived there.

Late–Stone Age Foragers

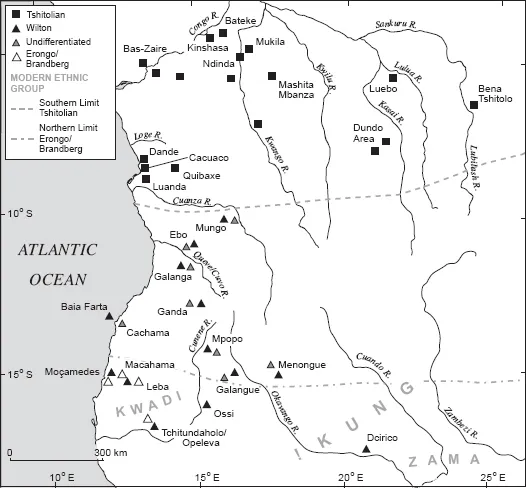

Humans first appeared in the record of West Central Africa well over a hundred thousand years ago and they have been present there ever since.3 By the Late Stone Age, that is, from well over ten thousand years ago, their tools and their rock art are found all over the area wherever archaeologists or other specialists (such as geologists) have looked for them (map 7).4

What ordinary mortals see only as small scatters of ordinary stones, specialists discern as tools that can be studied, and they will search for and often find other debris, such as remnants of animal bones or shells others do not even notice. In contrast, larger telltale shards of pottery which dot later sites are more easily recognized by laypersons. Since few archaeologists worked in West Central Africa, one would therefore expect known Late–Stone Age sites to be quite rare. Yet the number of known sites is greater than expected, which suggests that there once were many more people in the area than the layperson now imagines. It is reasonable to think that the number of foragers by the end of the Late Stone Age was at least as large, and probably larger, than their number by the middle of the twentieth century, especially since pastoralists or farmers have long dispossessed foragers of their most productive lands. Thus, we may accept that several tens of thousands foragers or more lived in the area on the eve of the introduction of ceramics.5

MAP 7. Late–Stone Age Sites in Angola and Congo

The ancient forager's way of life is known for the most part by the uses of their stone tools, the only tools which do not decay, as well as by durable remnants of their food such as nuts, while information about the practices of recent foragers in the region helps to interpret these finds.6 These people survived by gathering plants and hunting game. In recent times, the gathering of edible plants constituted the mainstay of the daily diet, and it probably has always been so, even though previously game was perhaps one hundred times more abundant than today. Today !Kung women still gather about one hundred species of plants, a good dozen of which can be called staples. Even two or three thousand years ago women, who were the main gatherers, already knew a great deal about which plants were edible, which ones were useful for what, where and when they could be found, how they should be processed and so on.7 All of this was the fruit of hundreds of generations of experience. Today, and formerly as well, such edible plants include tubers dug out of the soil with digging sticks weighted by bored stones (or kwe); fruits and nuts, some of which, such as the mongongo, are still found by archaeologists; melon, squash, pumpkins, calabashes, gourds such as the tsamma, which still is a main staple in the arid south, and the seeds of a few grasses crushed on grinding stones. Tubers were the most important as they provided the bulk of the carbohydrates, although pumpkins and melons were also crucial in drier areas and seasons because of their water content.8 Plants were so important to the food supply that one may think that in most places their availability was more crucial than that of game dictating where a camp was to be located and how long people would stay there before moving on, which implies that women had a major voice in making such decisions. And as plants tend to grow in the same spots year after year, camps may well have returned to the same locales year after year. Indeed their very exploitation also tends to assist their propagation by the scattering of nuts and seeds, and perhaps Late–Stone Age women were also already sticking tuber cuttings back into the ground. In this way even foragers leave ecological fingerprints on their environment.

While women gathered, men hunted. Game was abundant, especially in the grasslands where ruminants moved about in large herds. This not only stands in sharp contrast with the situation today but also contrasts favorably with its availability in the equatorial rain forests, whether one counts in terms of biomass overall, the number of species available, or the average weight per animal. Most meat was procured by hunting rather than by trapping, although the latter was also practiced. As the stone arrowheads and spearheads tell us, game was hunted by bow and arrow and by spearing. In most places the preferred animals seem to have been small- or middle-sized antelopes, although Richard Lee observes that big game, mostly larger ruminants such as elands, calculated in yield per weight per year contributed perhaps as much as half of the meat consumed. If the actual place where a camp was located was dictated by the supply of plant food, the seasonal roaming territory of that community was certainly dictated by the habits and presence of game.9 In most places away from the coast fish was but a minor source of food. Most of it was speared by harpoons. As to nutrition, plants were essential in providing carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins, and minerals while meat or fish were crucial for their proteins and salts.10

Because of their mobility, foragers owned rather few objects and most of these were made from organic materials that have not survived. But scraping stones show that they processed skins into leather fabrics for garments or bags, while trapezoidal or triangular microliths, probably glued to a wooden support, once were the cutting edge of knives, and heavy bifacial elements suggest axes and adzes for cutting and working wood. Containers certainly included calabashes and perhaps woven bags, string bags, and slings. Then there were ornaments such as stone or shell beads and perhaps lumps of vegetals or minerals such as redwood or specularite powder that were used as oils to protect and beautify the body.11 Some of these were exchanged over long distances. But none of these objects were considered to be just belongings with an objective value independent of who their owners were. Rather, all of them were thought of as mere extensions of the person who used them.

In most parts of West Central Africa, foraging provided a reliable, not too arduous, and perfectly satisfactory way of life as long as every day everyone obtained the expected plant and animal food. But nature is not a supermarket. Some women found more plant food while some of their neighbors might have an unlucky day. Some hunters were more skilled or luckier than others and bagged a large piece of game whereas some of their fellows returned empty-handed. Then some adults were too ill or too old to forage. Such uncertainties could be and were effectively eliminated by sharing. Sharing seems to have been the central value of all foragers then as it still was in the twentieth century. Those who had gave to those who had not, so as to even the score. But sharing was not giving. If one received today, one was expected to return the gift tomorrow. Rather than giving, we are talking here about a delayed exchange, a notion usually called hxaro after its designation in !Kung. Sharing created an ongoing relationship between the giver and the recipient, be they adults living within the same camp or not, be they related by kinship, as most were, or not. Sharing brought an indispensable predictability to foraging and turned this way of life into a highly satisfactory one, so satisfactory that it has been called “the original affluent society.”12 For did it not bring plants into the kitchen without the hardship of farming and meat into the larder without the trouble of herding? Did people think about their way of life and their communities in these terms? Unfortunately, the messages they left behind in the shape of paintings and engravings do not tell us, for they can only be interpreted, not understood.13

Be that as it may, there were, alas, side effects to this kind of affluence. Settlements had to remain both small and nomadic. Moving was difficult for the less mobile, old, or sick and it shortened their lives. Moving was also hard on pregnant or lactating women who could only cope by delaying a childbirth until the previous child could easily walk on its own. This trade-off thus entailed a significant demographic cost. It also entailed a considerable social cost, caused by the small size of all settlements. These were communities with intense face-to-face relations. These were certainly based on relationships of kinship and neighborhood. Everyone knew and dealt daily with everyone else. Most people were kin, and everyone behaved as if they were or were about to become kin. They all formed a single family in which rules of descent mattered only to define the boundaries of incestual relationships and hence of permissible marriage alliances, for there was nothing to inherit or to succeed to. The size of residential aggregates or camps was quite flexible and fluctuated according to seasons while individual mobility between various camps was high for men as well as for women. Except for sharing, an essential activity to alleviate risks, there was no incentive in this kind of community to develop more intricate social institutions on a larger scale.14 One could label these social organizations (vaguely enough) as egalitarian bilateral systems but even such a vague label is misleading. It hints at corporate groups that probably did not exist and it suggests the observation of invariant uniform rules in all matters regulated by descent, which was certainly not true then, just as it was not true among foragers in recent times.15

Despite the general identity-kit just drawn, it would be a grievous error to lump the foragers in the entire area together as if their way of life was the same everywhere, if only because different environments had produced different adaptations. Some foragers, for example, lived...