![]()

1

Crime and Society

Patterns in Deed and Word

The topical crime accounts that flowed from early presses were not fiction. Although some sloppily borrowed language from accounts of similar crimes elsewhere, very few seem to have been wholly invented. Even accounts of imaginary crimes, such as witchcraft and the ritual murder of Christian children by Jews, were normally based on real cases. Nevertheless, like modern true news accounts, they both mirrored and altered the picture of actual crime and its relationship to social surroundings. Partly by selection and partly by their modes of representation, they reshaped events to reflect cultural conceptions. This process did not necessarily require conscious manipulation; rather, it flowed naturally from the selection of, and reaction to, the crimes considered most worthy of public attention.

It is worth asking at the outset, then, some questions about how these texts depicted their social reality. Chapter 3 examines their relationship to the facts of some particular cases. Here I ask some broader questions about how their depictions mesh with historical findings about the social settings and determinants of crime in the transition from late medieval to early modern society. What were the sources of criminal threat? What kinds of people were portrayed as dangerous? What kinds of crimes were depicted, and how do the patterns of representation compare with what we know about the changing social dynamics of the early modern period? How did the transition into print change cultural images of crime?

First, a few general observations about the picture of crime they present. With their focus on the most heinous, crime accounts obviously magnified the profile of violent crime compared with more routine offenses. Here, killing was the most common of crimes, in scenarios to be examined at multiple points in this book. Although killings were always in the majority, the crimes recounted in print were many and various. The few that survive from before 1550 range widely, with no clearly observable pattern. Alongside a household killing by an apprentice, which was retold decades later and shared some elements with later familial killings, there were miscellaneous murders. A treasure-hunting charlatan dispatched a widow and her maid; a Catholic official killed his Protestant brother; most bizarrely of all, a peasant girl killed her very pregnant neighbor, stealing the baby in an attempt to press her lover into marriage.1 It is in the second half of the sixteenth century that some accounts begin to acquire a ring of familiarity, as household killers, serial murderers, or witches could echo the crimes of others. Still, there were reports that fit no common mold or related only peripherally. For example, the infamous case of the fraudulent giant belly of the maid of Esslingen was attributed to the witchery of her mother but otherwise had little in common with most witchcraft cases.2 There were occasional reports of political offenses, fraud, kidnapping, or blasphemy. Rather than attempt a comprehensive catalogue of the variety of cases, I have focused on common features and patterns as signals of the strongest cultural resonance.

Surviving crime accounts are quite sparse for the first half of the sixteenth century, a period of intensive development in print culture as well as in the modernization of criminal justice. We know that printers did produce such accounts, but too few remain to identify patterns; only a handful of my street literature sources predate 1550. But discussion of crime appeared elsewhere, notably in urban chronicles, a late medieval genre with its own distinctive aims. Beginning in the fourteenth century and into the sixteenth, members of urban elites produced such records, for various purposes but mainly to serve the political interests of the semi-independent imperial cities. Most paid scant attention to the crimes committed by ordinary people, focusing instead on crimes with political significance.3 This raised the profile of violent nobles as a “dangerous class” and contributed to late medieval criticism of feuding. When compared with the picture of crime that emerged in later popular print, they show how differences of genre as well as change over time could shape perceptions of crime.

The image of the violent noble predator was a product of the movement toward stricter standards of public order in the late Middle Ages. Although older scholarship took the robber baron as a sign of noble decline, more recent studies have tended to absolve him of lawlessness, if not of violence.4 Instead of an impoverished aristocracy driven to survive by criminal means, scholars have found canny and prosperous noblemen using the feud as a political tool to advance their fortunes. Under medieval law, a formally declared feud was a legitimate means for nobles to defend their rights—at least until the imperial ban on the practice in the General Peace of 1495.

To some, however, acts of private war looked increasingly like crime. Imperial cities were especially precocious in seeking to create islands of security in the Middle Ages, despite the Holy Roman Empire’s inability to police its vast territory. As early as 1302, the imperial city of Nuremberg forbade the carrying of weapons within its bounds; visitors were to deposit their arms—needed for self-defense in the countryside—with the innkeeper for the duration of their stay.5 In the chronic power struggles between towns and nobles, urban governments often sought to define nobles’ political violence as criminal and subject it to judicial punishment. In the urban chronicles, nobles appear regularly as miscreants. In accounts by leading citizens of Augsburg, for example, conflicts with nobles bulked large. The city of Augsburg pursued an extended feud in the 1370s with Jacob Püttrich von Bayern, which led to open war between cities and nobles. To the city fathers, however, the issues were matters of crime: Püttrich’s incursion into the city with a few of his men in 1370 led to the death of three burghers and to Püttrich’s arrest. When he escaped and took to capturing burghers, the town tried putting a price on his head.6 The burghers were more successful against Sebastian von Lauber, arrested in 1436 near Salzburg; he died of his wounds in prison, and two of his men were beheaded.7 Several more nobles were executed by cities as robbers during the 1440s.8 In 1444 a group of imperial cities joined together to attack the robber nobles von Waldenfels, who had been harrying traders from their castles.9 The practice of feuding continued into the sixteenth century, despite the imperial ban, as attested by the famous career of Götz von Berlichingen. Private violence by nobles was waning by the sixteenth century, however, as the nobles found other ways to promote their interests. Both the appeal of imperial law and the increasing power of territorial rulers contributed to the gradual taming of the noble feud.10

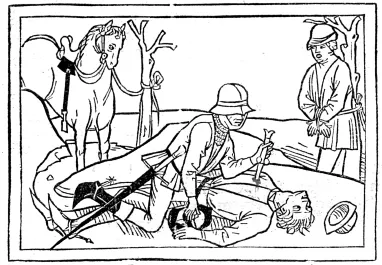

The violence of lawless nobles found its way into early print, appearing in the Spiegel des menschlichen Lebens (Mirror of Human Life) issued by the printer Günther Zainer of Augsburg in about 1475. This work addressed a lay readership, though at 174 leaves with illustrations, it was far more expensive than street literature. It shows a robbery scene in which a nobleman victimizes two defenseless peasants. Both text and image emphasize the incongruity of this abuse of the noble’s training and equipment for war (see figure 1). The robber’s horse is tethered to one tree, a peasant to another; the culprit leans over the unresisting body of a peasant on the ground, stabbing him with a dagger while reaching for his purse. The nobleman’s long sword, spurs, helmet, and chain mail contrast sharply with the dress and demeanor of the unarmed peasants. The author condemns the “baseness of human nobility” and finds such nobles unworthy of their status.11

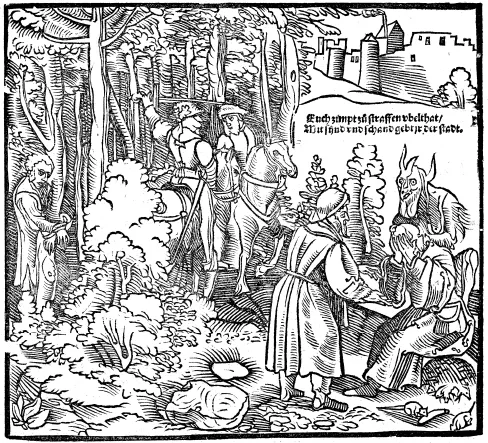

Urbanites were not the only ones to class nobles’ violence as criminal. Imperial reformers from within the noble class itself increasingly focused on promoting law and order. The growing move to criminalize feuding was crystallized throughout the empire in the General Peace issued in 1495. Reformers also contributed to a public discourse in which rogue nobles were a source of danger. Johann von Schwarzenberg, whom we will meet in the next chapter as a legal reformer, wrote in a range of genres and was a strong defender of both nobility and the law. His song “Against the Deadly Vice of Robbery,” first printed in 1513, assails the victimization of noncombatant peasants and burghers by men of violence.12 Especially abhorrent to Schwarzenberg was the complicity of magistrates who turned a blind eye to lawlessness: “Many who ought to fight it / with robbery connive; / If no land would abide it / no robber well could thrive.”13 Instead of paying for their crimes, the guilty parties caroused freely and even aimed public libels at those who, like Schwarzenberg himself, strove to enforce the law. In his view, they were perverting the entire concept of nobility by becoming marauders rather than protectors of those below them: “Nobility’s true ground/they utterly reverse” as “shepherds gobble sheep.” Everyone should be subject to law, and even to criminal justice if they violate it, for “The emperor’s true worth / and that of noble blood / above all gems on earth / is peace and justice good.”14 The song was later reprinted with Schwarzenberg’s German translation of Cicero (1540), accompanied by an illustration drawn from his collection of moral pictures with rhymed legends, the “Memorial of Virtue.” The woodcut shows a robbery victim bound to a tree, along with two armed men in the woods; in the foreground, a magistrate sits with his hands covering his face, the Devil behind him, ignoring the complainant before him (see figure 2). The accompanying rhyme gives the speech of the negligent magistrate, who finds it to his advantage to leave marauders unpunished; they are then beholden to him and can be used to intimidate others. Besides, his inaction saves him a lot of trouble:

Figure 1. A rogue nobleman murders a helpless peasant. (From Heinrich Steinhöwel, Der Spiegel des menschlichen Lebens [Augsburg, ca. 1475], fol. 21, Sig. 2 Inc.s.a. 1264, courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München)

Schwarzenberg insists that the magistrate is as guilty as the actual criminals for covering up their misdeeds.15

In popular crime publications of the sixteenth century, however, the nobility is largely tamed—a sign of both historical change and a shift in genre. While chronicles served the purposes of urban authorities, and reformers’ critiques might address mainly the very elites they hoped to reclaim, popular printing about crime had a far more miscellaneous clientele. Here, respect for social superiority was very much the norm. One of the most popular songs of the century harked back to a medieval conflict in which the forces of criminal justice prevailed, but with a certain nostalgia for the older code of noble honor. Based on the pirate-noble Klaus Stortebeker and his downfall in Hamburg in 1402, it was frequently reprinted and widely reused as a tune; a number of crime accounts of robbers, familial killers, and witches were set to it.16 The song implicitly aligns his fate at the hands of Hamburg authorities with those of the robbing nobles arrested by other cities in the fifteenth century. Stortebeker and his fleet of privateers had long harried the ships of Hamburg and its trading partners in the Hanseatic League. The city caught and killed as many of his followers as it could and finally launched a major expedition to root them out. The defeated Stortebeker sought an honorable surrender for himself and his men, and according to the song, this was agreed to by the opposing commander, Simon von Utrecht. But the city authorities would have none of it. The song emphasizes the surprise that awaited the pirates: “When at the Elbe they arrived/Nothing good there met their eyes; / They saw the heads there mounted. / My lords, those are our comrades, / Then Stortebeker thought.”17 They were executed in Hamburg the next day, having asked for and been granted signs of honor: music, drums, and the favor of dying in their best clothes. Implicitly, this song endorses the view that such noble adventurers should not have been subjected to treatment as criminals. The switch from honorable surrender to trial and execution appears as a betrayal of Stortebeker’s trust. In this version, even the implacable Hamburg authorities concede some of the trappings of an honorable martial death.

Figure 2. A judge turns a blind eye to the crimes committed by nobles. (Johann von Schwarzenberg, Der Teütsch Cicero [Augsburg, 1540], shelfmark Mason R. 216, fol. 93r, courtesy of Bodleian Libraries)

The few nobles who appear in crime accounts of the sixteenth century are mainly on the right side of the law, protecting the weak and ensuring that justice is carried out. They figure among the admirable authorities who track down criminals and defend public security. In more than one report on the sale of a pregnant wife to killers in the later sixteenth century, it is a nobleman who happens by while hunting and saves the woman.18 There are a few exceptions, as in a 1567 song about the execution of Wilhelm von Grumbach, chief of a group of “empire-spoiling people” and a holdover from the bad old days of feuding.19 Another bad apple, in a song from 1570, attacks worthier nobles without even the pretense of honorable behavior. Though pretending friendliness, he watches for an opportunity to rob and murder them with the help of his two henchmen. He wounds two of the nobles but then in flight...