![]()

JAMES DOW MOVED TO Montgomery County sometime between 1870 and 1876. Born a slave in Roanoke County in 1850, he left no account explaining why he decided to move, but it may have been for a woman. Three years after his emancipation, in April 1868, Dow began working as a laborer for the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. He was living near Salem at the time, on the western edge of Roanoke County, but from there the section crew to which he belonged moved east and west along the rail line performing regular maintenance on the track and roadbed. This brought him into eastern Montgomery County, and there he met Frances Taylor. Frances, who went by Fanny, was the daughter of John Taylor, a farm laborer living near Big Spring, and his wife Charlotte, and like James Dow, she had been born a slave. When and how James and Fanny met remains a mystery, but they married in 1876, when he was twenty-six and she was seventeen, and spent the next half century building a life together in Montgomery County.1

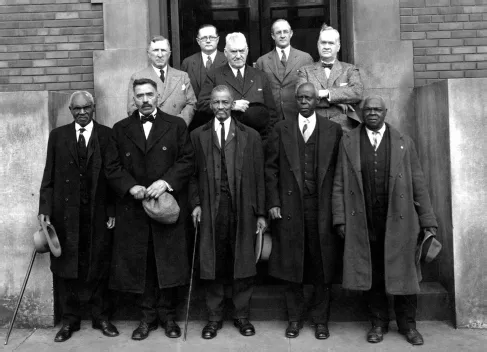

James and Fanny Dow initially lived with Fanny’s parents but eventually moved into their own home in the Brake Branch neighborhood, just outside of Big Spring, or Elliston, as it was renamed in 1890. James continued to work for the successors of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, retiring from the Norfolk and Western in 1918 after fifty years as a section laborer (figure 2). He and Fanny also farmed the small tract of land on which they lived and raised twelve children born between 1877 and 1904. As their children came of age, though, the younger Dows found themselves living in a county and a state that offered African Americans fewer economic and political opportunities than it had in their parents’ day and in which racial attitudes were hardening and growing more bitter. Some of the Dows’ children remained in Montgomery County, and some of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren remain there still. Others, however, elected to leave in search of better opportunities in West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.2

FIGURE 2. James Dow (front row, center) in 1930. The photograph was taken at the time of his inclusion in the Colored Division of the Veterans Association of the Norfolk and Western Railroad in recognition of his fifty years of service to the company. (Courtesy of the Norfolk Southern Corporation)

The story of the Dow family encapsulates the broad demographic history of Montgomery County’s black population in the half century following the Civil War, and this chapter provides a broad overview of how and why that history unfolded as it did. For some two decades after the Civil War, the county’s African American population grew as individuals and families moved into the county and with those living there already established and maintained African American schools, churches, social organizations, and neighborhoods throughout the county. These institutions and communities were always distinct and often separate from their white counterparts, but they were never isolated from the larger society of which they were a part. By 1890, though, black migration into the county had slowed while that out of the county had begun to accelerate. By the dawn of the twentieth century, Montgomery County’s black population had started to decline and would continue declining until the 1960s. Like the children of James and Fanny Dow, members of Montgomery County’s black community often moved out in search of better opportunities, but like the Dows, the county’s black community never disappeared. Today, more descendants of James and Fanny Dow live in other counties and other states than in Montgomery County, but the family remains part of the county’s African American community, and that community remains an essential part of the county and its history.

During the course of the Civil War the black population of Montgomery County had declined significantly. John Inscoe and Gordon McKinney have found that slave populations in western North Carolina often rose during the war as residents of the region bought slaves from panicked owners farther east or as easterners fled west with their slaves, and Jaime Martinez has noted that wartime demand for salt brought more slaves to labor in the salt works of Southwest Virginia. In Montgomery County, however, there was little evidence of such inflows. There were white refugees who may have brought slaves into the county. Isaac White Sr., for example, moved from Upshur County, in what became West Virginia, to Montgomery County during the war and may have brought some of his slaves with him when he relocated. And after the war the Freedmen’s Bureau did provide transportation from Christiansburg to Atlanta for two girls “who refuged here with a Mrs. Sullivan during the war.”3 Overall, though, the war led to a decline in the number of slaves and free people of color in Montgomery County. More than one hundred of the county’s slaves or free men of color were impressed or hired to work for the Confederate government or military during the war, and hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children fled the county when Union troops passed through in 1864 and 1865.4 Evidence of both the absolute decline in population that occurred during the war and the broad nature of that decline appears in a census of Montgomery County’s “colored population” conducted by the Freedmen’s Bureau in August 1865, just a month after opening its Christiansburg office. The bureau found a total black population of just 1,573—down a third from the 2,366 reported on the federal census in 1860. It also found that the age and gender distribution within that population was still quite close to what it had been in 1860. Males age fifteen years and older, for example, still made up 26.1 percent of the county’s black population in 1865; this was down from the 27.4 percent reported in 1860, but not dramatically.5

The 1865 enumeration certainly overstated the decline, though, as it missed a number of freedpeople known from other sources to have been in the county that summer.6 Moreover, whatever the exact level of the decline, it was quite short lived; another census, taken in 1867, showed that the county’s African American population had already begun growing again. By 1867 it had regained its prewar size, and it continued to grow steadily for at least another fifteen years. By 1870 it had grown to 2,882—up more than 80 percent from its wartime nadir and almost 22 percent above its 1860 level. It grew by another 47 percent between 1870 and 1880, to 4,227, and probably grew for several more years after that before starting to decline. The best estimate of the county’s population between decennial censuses comes from the annual reports of public school enrollments, and by that measure Montgomery County’s African American population probably peaked during the 1882–83 school year at an estimated 4,400.7

Such growth in absolute numbers is not surprising. Gordon McKinney found that throughout the mountain South, the number of African Americans rose between 1870 and 1900. What is unusual, however, is that in Montgomery County African Americans also increased as a percentage of the total population. They made up 23 percent of the county population in 1870 and 25 percent in 1880, compared to 22.4 percent in 1860. After peaking in the 1880s, however, both the number of black residents and their share of the total population percentage began to decline, falling to 3,515 (19.8 percent) in 1890 and 3,381 (17.1 percent) in 1900. It is difficult to express properly the rate of decline in the county’s black population at the turn of century because Radford, which had about five hundred African American residents at the time, became an independent city in 1892. Whenever one makes that adjustment to the county’s population, the black population shows a precipitous and misleading drop. Adjusting for that one-time drop, however, does not change the overall story; the final years of the nineteenth century saw what Jeffrey Kerr-Ritchie called “the roots of the later Great Migration.” Montgomery County’s black population began to decline by about 1885 and continued to decline steadily until the 1960s.8

Both the growth and the decline in Montgomery County’s black population after the Civil War were due, in part, to natural demographic factors—births and deaths—but the main factor driving it was migration. In the decades after the Civil War, hundreds of black men, women, and children moved into or out of the county, and sometimes did both. Obviously, the volume and direction of migration changed over the years, but so did the factors driving it. Three factors seem to have been most evident during the decades following emancipation, though their relative importance shifted over time. Family provided a very strong motive to move, at first, but then declined and soon became a factor reducing the likelihood that an individual would migrate. Economics was the most consistent factor. African Americans were always looking for better access to land and better job opportunities, but whether that served to attract them into the county or pushed them to leave changed over time. It seems to have drawn them into the county for the first twenty years after the Civil War but by the mid-1880s seems to have become an important factor leading to out-migration. The third factor—racism, race relations, and the status of African Americans in the county—also seems to have fluctuated as a factor influencing migration out of Montgomery County. As Steven Hahn found elsewhere in the South, racism often triggered black emigration in the late 1860s and again at the turn of the century but was a less important factor for much of the 1870s and 1880s.9

In the years immediately after emancipation, the most powerful factor behind black migration into and out of Montgomery County seems to have been the desire to reunite families broken by slavery.10 Slave families in antebellum Virginia had often been separated by sale or by forced migration with their owners, and the expansion of slavery in Montgomery County during the 1850s had brought hundreds of new slaves to the county, many of them from Virginia’s Southside region. The county’s cohabitation register, compiled in 1866 to legalize slave marriages and families, indicates that just 47 percent of the adults who had been enslaved in Montgomery County had been born there. This figure rises to 60 percent if one also includes the counties immediately adjacent to Montgomery—a sort of “Greater Montgomery County”—which might be more appropriate in light of the fact that several large landowners on the eastern and western edges of the county also owned land in Roanoke or Pulaski County.11 Still, the cohabitation register suggests that at least 40 percent of the adult slaves living in Montgomery County in 1860 had been brought or sent there. Some of these traveled alone and left all of their relations behind, but even those who made the journey in family units left more distant kin near their former homes, and those who did not arrive in complete families often left parents, spouses, and children as well. Meanwhile, slave families that were already established in the county were sometimes broken as members were sold or manumitted or escaped. Susan Lester, for example, was manumitted by Mary Wade in 1860 along with her two younger sons. Wade retained Lester’s older sons, however, and they remained in Virginia when their mother and brothers moved to Ohio later that year.12

Numerous studies have shown that restoring family ties was a critical priority among freedpeople following their emancipation. Throughout the antebellum South, slaves had run away to rejoin family, and as soon as the Union army began to occupy parts of the Confederacy, slaves escaped to Union lines and began searching for family. As early as 1862, the Christian Recorder, a newspaper published by the African Methodist Episcopal Church, began carrying announcements from former slaves asking for information about family members sold away. It continued to do so well into the 1870s, as did a number of other papers. Only one resident of Montgomery County is known to have used the Christian Recorder or similar outlets to look for family, but others also showed their determination to reunite families broken in slavery. Susan Lester, for example, explained her decision to return to Christiansburg by telling her banker in Ohio: “In slave time I left Va. and going back now I have two sons there and other relations and I would like to have my home there.”13

Agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau were often interested in family reunification as well, and among the first records generated by the bureau’s office in Christiansburg was an accounting of money provided by Captain Buel Carter during the summer of 1865 to cover the costs of railroad travel for reuniting several families in Southwest Virginia. When Charles Schaeffer took over as the agent responsible for Montgomery County in May 1866, he also demonstrated a desire to help reunite the families of freedpeople. As Heather Williams has recently pointed out, though, even bureau agents who wanted to help reunite black families had very limited resources with which to do so. Bureau policy was to provide financial support only for those who were truly destitute and, even then, only if the failure to do so would force the government to support them. Those who could work would have to pay their own way. Schaeffer, therefore, was able to cover the cost of bringing Sarah Winfrey, “an aged colored woman,” from Bristol, where she was “without home or friends,” to join her daughter and son-inlaw near Blacksburg in late 1866. But when Henry Poor, a freedmen living in Lynchburg, asked Schaeffer for help bringing his ten-year-old son, Lewis, home from Montgomery County, it was a different story. Schaeffer helped arrange the boy’s passage to Lynchburg, but his father had to cover the cost himself. Bureau policy was not to provide financial assistance except in “extream cases,” and Lewis Poor did not qualify.14

The extent to which family reunification brought freedpeople into Montgomery County is most evident, perhaps, in the county’s cohabitation register. The register indicates that approximately a quarter of married black adults in the county in 1866 had moved there since gaining their freedom. Some of these moved to rejoin a spouse or children. Thomas Baker, for example, apparently moved to Montgomery County from Spotsylvania County to join his wife, Martha, and three of the couple’s children. In other cases, freedpeople who had been born in Montgomery County and had been taken or sent elsewhere moved back to rejoin their extended families. Frank McNorton, Frank Moon, and Ellen Fraction Raglin, for example, had all been born in Montgomery County but seem to have been among the slaves that Catharine Jane Preston took with her to Pittsylvania County when she married George H. Gilmer in 1845. They remained in Pittsylvania after Catharine Preston Gilmer died, but following their emancipation they returned to Montgomery County and brought with them spouses and children born elsewhere.15

Immediately after emancipation, then, family reunification was a major factor motivating freedpeople to move to Montgomery County, but by the early 1870s it was probably a less significant factor than economics was. Growth of the county’s black population was greater during the 1870s than during any decade in the county’s history except the 1850s, when slavery had expanded so dramatically following completion of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, and the early 1880s marked the high point for African Americans as a percentage of the county’s total population, at 25.3 percent. Much of this growth seems to have been a result of young adults moving to the county in search of better economic opportunities.

Most of these opportunities were in agriculture. In many parts of Tidewater and Piedmont Virginia, the tobacco-based economy had faced severe challenges long before the Civil War. Wartime destruction, weather, and white opposition to free black labor added to those challenges, and parts of eastern and central Virginia often saw large numbers of unemployed freedmen immediately after emancipation.16 In Montgomery County, on the other hand, commercial agriculture had really begun to expand only when the railroad arrived, in the mid-1850s, and still had room to expand when the war ended. Moreover, while some of the region’s infrastructure had been damaged or destroyed during the war, destruction there was modest compared to that seen elsewhere. As result, agriculture in Montgomery County escaped the postwar decline seen in many parts of Virginia. Statewide, improved acreage in Virginia fell by a quarter between 1860 and 1870 and then rose by just 4 percent in the following decade. In Montgomery County, though, improved acreage rose by 9 percent between 1860 and 1870 and by 24 percent between 1870 and 1880. And though whites in Montgomery County sometimes complained about free black labor and occasionally threatened to replace black workers with white immigrants, most quickly realized that if they wanted to make their land profitable they would have to employ freedmen. Moreover, unlike white landowners in some parts of the postwar South, those in Montgomery County were also willing to sell land to freedpeople.17

Rising demand for labor in other sectors of the economy also meant that black families in Montgomery County could complement farming with other employment, as the family of James Dow did. The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which became part of the Atlantic, Mississippi, and Ohio in 1870 and the Norfolk and Western in 1881, used black labor extensively on its section gangs—men who maintained the track and roadbed—and also as brakemen and as laborers around i...