![]()

[1]

The Domestication of Tradition

In 1944, writer James Agee published a scathing commentary in the Partisan Review on the “corruption” of folk culture, in response to writer Louise Bogan’s lament that the rediscovery and revival of pre-urban folkways after the First World War had “thoroughly bourgeozified [sic]” folk tradition. Taking up Bogan’s complaint that these revitalized folkways had been rendered useless to artists except those “immersed in middle-class values,” Agee focused on the decay of jazz since the mid-1920s—in particular the abandonment of the music of the southern backcountry, street bands, and race records in favor of the sophisticated sounds and forms that pandered to white, middle-class tastes: the music of Duke Ellington, Hazel Scott, and Paul Robeson. Louis Armstrong’s new version of “West End Blues,” according to Agee, was “adulterated, sugared-and-spiced,” and Hazel Scott’s music was decadent and affected, the sort “one could probably pick up, by now, through a correspondence school.” With scorn, Agee also discarded the “mock-primitive demagogic style of the great bulk of WPA and leftist painting,” Oklahoma!, and the work of Carl Sandburg. He labeled such constructions “pseudo-folk.”1

Agee feared that contrived and self-conscious art forms were replacing the true indigenous cultural expressions of the people. Intellectuals like Agee and Bogan were not alone in debating the nature and status of the folk in America during the 1930s and 1940s. Commentary also came from scholars in the academy, public intellectuals, and the popularizers who were helping to flood the marketplace with consumable versions of tradition; through the act of consumption, even the American middle class played a role in defining America’s folk.

Indeed, consumers in the 1930s had many opportunities—in addition to those descried by Agee—to bring America’s folk into their own consciousness and sometimes into their homes. Museums displayed early American arts and crafts; singers, dancers, and musicians entertained at organized folk festivals; country music arrived in homes via radio and record albums; photographs and literature in popular magazines and books introduced Americans to the folk of isolated, often rural communities; and, of course, handcrafted, functional goods made by women and men in the Southern Appalachian mountains and in southwestern pueblos decorated modern homes. This was the decade of—to name only a few examples—the National Folk Festival, photographs by Walker Evans, Russell Lee, and Dorothea Lange documenting the everyday life and customs of America’s common people, songs of labor and life by Woody Guthrie and Aunt Molly Jackson, Thomas Hart Benton’s vivid paintings of the nation’s vernacular culture set in localized landscapes, Zora Neale Hurston’s renderings of African American folktales, the Grand Ole Opry, the description and celebration of the nation’s regions and communities in the Federal Writers’ Project’s American Guide Series, and the enshrinement of American decorative arts in the images compiled for the Index of American Design.

Such a diversity of media produced a variety of interpretations of America’s vernacular cultures, and Agee may have tolerated some expressions better than others. Agee’s essay compels, however, because it reveals some of the tensions and conflicts that shaped both popular notions of tradition and also the cultural products of this enthusiasm for the folk during the years between the two world wars. Agee lamented the loss of the pure, the “authentic,” lately polluted by some of the very forces that brought this vibrant culture to him and to the world—the radio, the recording industry, and mass communications. This juxtaposition was an important one in the 1930s. Middle-class Americans were becoming more and more aware of the United States as a nation made up of local and unique communities with particular rituals, artistic forms, and ways of life that were very different from their own and that perhaps had much to offer a national culture. Yet the very forces that brought these individual cultures into wider contact with larger numbers of Americans also inevitably reshaped them to make them less different. Agee lamented the process by which unique cultures were domesticated, or made familiar, as they were packaged by and for a nation of consumers in an increasingly corporate and capitalist America; in Agee’s eyes, these cultures were homogenized.2

In the 1930s, many Americans encountered the folk primarily through the latter’s handcrafted goods; a majority of the “folk” handicrafts purchased in this decade were made by Native Americans or by people residing in the mountains of the Appalachian South. By this time, mountain crafts typically had become products transformed by the complex interactions of the producers and their cultures, social reformers and settlement schools, middle-class consumers, industry, and government. Consumers were purchasing more than a newly conceived good, however; in no small part, they were also purchasing an icon of an imagined past, provided by a group of contemporary citizens who had assumed the task of preserving a carefully selected version of the nation’s heritage in the present. At the same time, all the structures and ideals of a culture dedicated to industrialism, consumption, and rationality were reshaping the production, delivery, and meaning of the folk handicrafts of Appalachia.

James Agee did not address the domestication of Southern Appalachian culture—he chose other cultural products for his reflections on consumer culture. Yet Agee’s criticisms alert us to important and commonly held scholarly and popular notions about folk and tradition that prevailed through the first half of this century. Although the meanings assigned to these cultural categories were contested, particular motifs persisted. As ideological constructs, definitions were shaped by notions of gender, race, and ethnicity and by social and economic relations in specific historical contexts. Thus we must consider exactly who defined the folk and tradition. Who were the people they identified as the folk, and what were their characteristics? How did notions of “authenticity” and originality shape the construction of cultural categories? What was the relationship of folk to the past and to tradition?

Middle-class Americans were introduced to the folk through the work of three major groups in the 1930s: academic researchers, public intellectuals, and those who sought to popularize traditional cultures. Understanding the complex evolution of the terms folk and tradition depends upon our consideration of both the academic and the popular arenas of their creation.

Photographers for the Farm Security Administration captured the daily lives and customs of many of America’s ordinary people. Here, Jorena Pettway and her daughter of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, make chair covers from bleached flour sacks and paper flower decorations in 1939. Pettway also made the twig chairs. (Photograph by Marion Post Wolcott; courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USF 33-30353-M2)

The writers, artists, musicians, intellectuals, and reformers who “rediscovered” the folk in the 1930s evinced what Alfred Kazin described as America’s preoccupation with “news of itself”—a self-conscious urge to identify the sources of its uniqueness as a culture and a nation and to build an identity based on those sources. From this impulse came the explosion of descriptive journalism, documentary photography and films, and social literature that offered “authentic” reportage of the rich details of daily existence in various areas of the United States. As Americans struggled to define an “American way of life” that did not rely on material wealth in economically troubled times, they looked to agrarian societies, small towns, and the minutiae of everyday life—past and present—as repositories of values and community esprit.3

In America’s quest for itself, tradition played a critical role, for this was an age that continually invoked the past even as it embraced modernism. Tradition, in the 1930s, meant knowledge, ideals, and customs informally handed down from past to present over several generations. However, the term often invoked a distant past that was vague and conflict-free, untroubled by class, racial, or ethnic divisions. Derived from this idealized national past, tradition served as a crucible of simplicity and self-sufficiency—ideals that might guide a unified nation through difficult times. As preservers of tradition in the “modern” world, the folk provided a crucial link to America’s roots and cherished ideals; they helped make the past usable.4

Indeed, during the 1930s, the boundaries of official or public tradition expanded to embrace the everyday lives of ordinary Americans, not just heroic and exemplary ones. Carl Sandburg turned to folklore as the basis for his epic poem on the national spirit, “The People, Yes” (1936); in his dramas, Paul Green celebrated the customs and lives of his fellow southerners as well as historical characters and events. Collectors like Henry Mercer and Henry Ford sought out the everyday objects of common people and enshrined them in their museums; state and local historical societies flourished; and new historic sites, markers, and military monuments commemorated universal figures rather than high-ranking heroes. This new egalitarian emphasis also appeared in the state guides compiled by the Federal Writers’ Project. These guides, which included stories of ordinary citizens as well as leaders and statesmen, revealed that the past was “not always glorious, but no matter; its glory lay in its being past.”5

Invoking their history could help Americans live in the present while reconciling present days with times past. Restorations such as Colonial Williamsburg could teach contemporary citizens about liberty and personal integrity by recalling the honorable leadership that presumably flourished in early America. Ironically, even in the midst of economic collapse, some industrialists like Henry Ford used the past to demonstrate the triumph of industrial capitalism; his collections of tools and machines at Greenfield Village offered visitors a history of technology as progress. Such artists as Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth reconciled old and new, too, bringing vernacular expressions from the past together with new technology in their work.6

Nevertheless, the fascination with traditional ways expressed middle-class Americans’ ambivalence toward industrialism, which might offer material comforts but denied the human values they perceived in “simpler” cultures and in their country’s past. Tradition and its bearers, the folk, served as critical lenses through which to view industrial America, yet they incorporated the familiar values and structures of America’s corporate, capitalist culture.7 This was the very fate of an antimodernist critique generated by the Arts and Crafts movement that captured American imaginations toward the end of the nineteenth century.

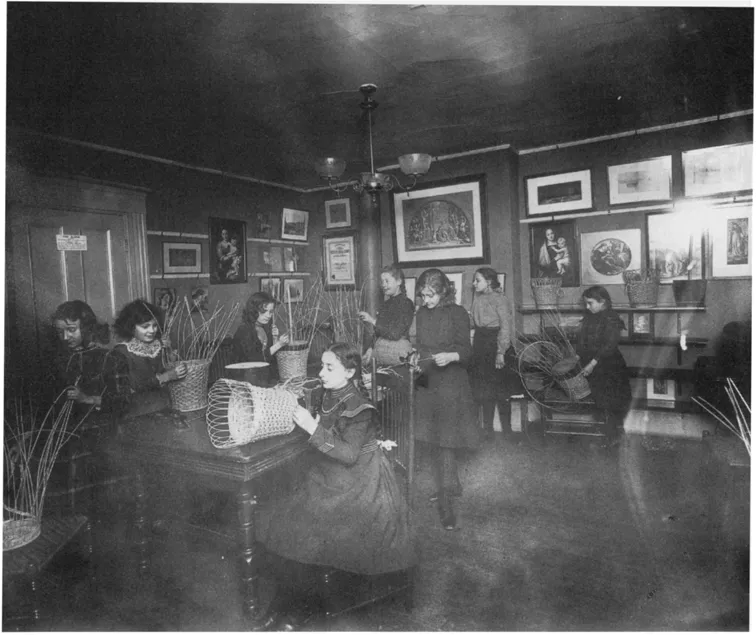

Indeed, the resurrection of tradition epitomized by the folk revivals of the 1930s shared some ideological foundations with the Arts and Crafts movement. Both looked back, with some nostalgia, to an idealized preindustrial and precapitalist past as the basis for a healthier national order. Both advocated an implicitly antimodernist position: the machine and its accompanying reorganization of work degraded factory production and labor, and ultimately modern urban life. Simple living through handicraft production offered a balanced existence, a recovery from decadence, and regeneration for craftspeople and consumers alike. In reform circles, active players in the Arts and Crafts movement such as Jane Addams devoted themselves to the revival of folk traditions among their settlement neighbors, with their efforts frequently focusing on crafts. Thus, at Hull House, the Labor Museum displayed and promoted the Old World craft processes of immigrant neighbors, just as the Folk Handicrafts Council at Boston’s Denison House offered its version of transplanted eastern European customs. During the lean years of the Depression, however, it was economic necessity that bolstered the moral virtues of simple living.8

The Arts and Crafts movement and the folk handicrafts revival in the United States also shared a common source of leadership. In these endeavors, middle-class women found a way to create spheres of influence even within a progressive but still patriarchal and hierarchical culture. Both revivals provided such women with opportunities to blend social and cultural reform, pursuing moral goals and ideals in dedication to improving the domestic environment and nourishing the human spirit. In both the handwork of their own ancestors and the folk crafts of other cultures they discovered a unique women’s presence, and they saw such craftwork as a wholesome alternative to industrial labor for wage-earning women. These middle-class reformers were central figures in Arts and Crafts-inspired revivals in settlement houses and women’s clubs, where they established craft industries that employed female rural and urban wage earners and redefined women’s skilled handwork as art.9

Basketry class at Denison House, Boston, 1915. (Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College)

Their reform efforts were also instrumental in the feminization of handwork and particular craft skills. A very few crafts, such as woodworking, were understood to be men’s work. But the foundation of most reform craft enterprises was built on domestic handicraft traditions such as weaving, and in these, reformers maintained gendered divisions of labor. Moreover, they promoted craft labor as a means of supplementing the family income; childrearing and household tasks were to remain women’s—even wage-earning women’s—primary duties. The piecework rates the women received for their handwork were quite low, and craftwork was not considered an adequate or appropriate source of income for male breadwinners. In essence, women and the other marginalized groups of Americans whom reformers trained as craftworkers—such as Indians, southern mountaineers, and Eastern European immigrants—found that their roles as caretakers of tradition required no shift in the balance of power.

In the United States, the Arts and Crafts movement developed less as a critical voice than as an aesthetic commentary and taste-making exercise that avoided the economic and social questions posed by the movement’s British leaders, John Ruskin and William Morris. Arts and Crafts, as an aesthetic and as a way of life, became the property of America’s wealthy. Some Arts and Crafts reformers fostered the production of fine handcrafted goods for wealthy consumers, while others devoted themselves to redirecting the tastes of working- and middle-class people away from mass-produced objects. In the hands of America’s elite, the Arts and Crafts movement evolved into a campaign for “stylish rusticity” associated with restored farmhouses and country cottages and with handcrafted furnishings, all offering temporary escape from the vicissitudes of modern, urban life. Simplicity came to mean “good taste,” Thorstein Veblen complai...