![]()

1

FOR THE GLORY OF GOD AND THE GOOD OF THE PLANTATION

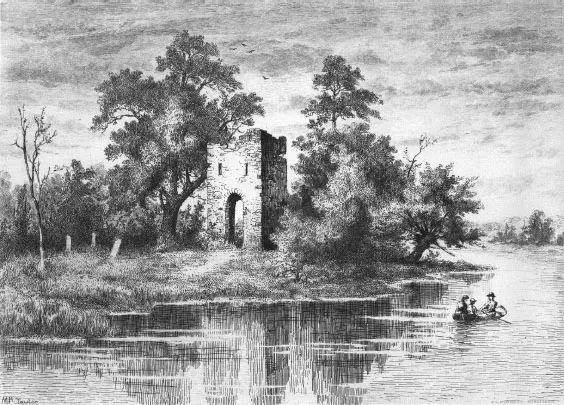

This late nineteenth-century etching by Margaret M. Taylor (courtesy of the Library of Virginia) for Historic Churches of America: Their Romance and Their History (Philadelphia, ca. 1891–94) depicts the ruin of the church at Jamestown. In a smaller church that once stood near the site of the 1640 tower, the first General Assembly of Virginia met from 30 July through 4 August 1619. Nearly two centuries after Jamestown ceased to be the capital of Virginia, portions of the town site reverted to a state not unlike what the first settlers encountered in 1607. The lasting importance of what took place in Jamestown during the seventeenth century made the island a popular tourist destination and, as the title of the illustrated volumes for which the image was produced suggests, generated romanticized interpretations of the past, to which this image in turn contributed. The reality of what the members of the first assembly did is fundamentally important for understanding Virginia’s history and political culture.

THE CHURCH AND THE STOREHOUSE in Jamestown were the most substantial buildings that the English settlers erected during their first years in Virginia. From the beginning they served both God and Mammon. On Friday, 30 July 1619, something new and important happened in the church. The governor, the members of his advisory council, the treasurer, the secretary of the colony, and twenty-two other men gathered there to make some regulations for the better management of the colony. They acted under an authorization of the Virginia Company of London, which had just received from the king the new Charter of 1618, soon to be known as the Great Charter, in part because of what began in the church that day. It was the little colony’s second change of administration. The dysfunctional council of 1607, of which Captain John Smith had once been president, gave way in 1610 to a military government that imposed order on the English outpost. By the time King James I granted the Great Charter, the English-speaking residents of Virginia had made themselves more or less self-sufficient. They had imported cattle and swine, planted grain, and made good use of the fruits and the game and fish that the land and water provided in abundance after fresh rains resumed and ended a long and severe drought midway through the military regime. In 1619 they began again.1

That the colony had survived the first dreadful years was almost miraculous. Virtually everything that could have gone wrong in the beginning had gone wrong. Drought had reduced the Indians’ harvest on which the first settlers planned to rely, and the men of 1607, following the company’s instructions, carefully selected a particularly poor site for settlement in a time of drought, although they did not know that one of the worst dry spells in all of Virginia’s history had just begun. By drinking water from the river or from the well that they dug a few paces from the riverbank, they may have contracted an enervating low-grade salt poisoning. Jamestown was also adjacent to a marsh that exhaled a foul-smelling breath, but it was not the marsh gases, it was the malaria that the marsh’s mosquitoes carried that made people sick or die. The resident Indians were sometimes helpful, sometimes harmful. Until Captain John Smith took charge in 1608, the colony’s leaders had squabbled among themselves and the enterprise looked doomed, but he took command and ordered that men who did not work would not eat. After Smith left in 1609, the people hid themselves in the little fort at Jamestown and during the following winter, which soon was called the starving time, died miserably of disease and hunger, reduced to eating rats and snakes, even the corpses of other men and women.

During the first years of military government, the acting governor, Sir Thomas Dale, made Captain John Smith look like a softie. Dale enforced to the letter the brutal Laws Divine, Moral, and Martial. He executed men who blasphemed, shirked their responsibilities, or refused to obey. When a man stole food from the common stock, Dale had him tied to a tree and left him there to starve to death in plain sight, for the encouragement of the others, as the French would later say. But Dale made the colony succeed. He ordered men to plant grain, raided Indian towns for food, destroyed other Indian towns, erected palisades to protect the little settlements, and created a new town upriver on a high, easily defended bluff. He called it Henricus after the king’s son. Dale also allowed men to farm small tracts of land for themselves rather than work communally on company land. By the time he returned to England in the spring of 1616, having been in charge for more than half of the colony’s short history, the future prospects for Virginia had begun to look bright. He took with him one of the first large crops of Virginia tobacco and also its grower, John Rolfe, and also Rolfe’s wife, Rebecca, or Pocahontas, or Matoaka.

On the same ship with Dale, the Rolfes, and the tobacco was an Indian man, Uttamatomakkin, or Tomocomo. He was a principal adviser of Wahunsenacawh, also known as Powhatan, the paramount chief who thirty or forty years earlier had assembled an affiliation of Indian tribes into the most impressive alliance on the mid-Atlantic coast. His chiefdom, called Tsenacomoco, covered the same part of the earth as the English company’s colony, called Virginia, and he was worried. During his long life he had seen Spaniards and Englishmen come into the great bay of Chesapeake in their ships and then leave. Some tarried a few days or weeks, but they all soon left except one group of Spanish Jesuits who in 1570 established a mission on the banks of the York River, but the Indians wiped it out a few months later. The English who arrived in 1607 showed signs of staying, but they did a poor job of surviving until after the drought broke and Dale brought over cattle, hogs, and heavily armed soldiers in 1611. By 1616 they had remained far longer than any other Europeans, and Wahunsenacawh sent Uttamatomakkin to England and directed him to count the men and the trees there in order to learn how many more Englishmen might come and whether they merely came for trees to build more of their ships. It is not certain whether Wahunsenacawh, who died in 1618, ever received a report of Uttamatomakkin’s observations. In fact, so numerous were the men and trees in England that he gave up trying to count them; the stick on which he notched his tally was too short. If Wahunsenacawh did not learn, he probably suspected that the population of England and its technological resources were so superior to those of his people that the future prospects for Tsenacomoco no longer looked bright.

By the summer of 1619 the English settlers numbered several hundred and lived in four little towns and worked on several company-owned farms, called particular plantations or hundreds, along the James River. They had erected a large church building in Jamestown, probably the only European-style building in the colony large enough that all of the members of the assembly could meet in one room without having to shift casks of tobacco, supplies, and trade goods out of the way. The settlement on the island had been “reduced into a hansome forme, and hath in it two faire rowes of howses, all of framed Timber, two stories, and an upper Garret, or Corne loft high, besides three large, and substantial Storehowses, joined togeather in length some hundred and twenty foot, and in breadth forty.” Adjacent to the original town site were “some very pleasant, and beutiful howses,” two blockhouses, “and certain other farme howses.”2

Governor Sir George Yeardley, the council members, Treasurer Edwin Sandys, Secretary John Pory, and the other men who assembled in the church in Jamestown on that 30 July 1619 had all, so far as can be determined, arrived in Virginia after the starving time winter of 1609–10. The colony that the Virginia Company had planted in the New World was a mere twelve years old, but it was already by far the longest-lasting English settlement in the Western Hemisphere.

Beginning that Friday in July 1619, those men completed the formation of a new local government. They still operated under the general superintendence of the governing council—the board of directors, as it were—of the Virginia Company back in London, and they still functioned within limits that the king’s charter imposed on them; but the new charter empowered a governor and a Council of State to govern the colony, and the governor’s instructions authorized him to summon a second council, called the General Assembly, to make the laws. What they did and how they did it influenced the whole future of Virginia’s history and the history of the United States. The political history and culture of both began with what the company’s officers and employees did that day in the church in Jamestown.

When the men met in the church that morning, it was probably not the first time that day that they had been to the church. From the very first landing of English-speaking people in Virginia, the company’s instructions had required all of the settlers to attend the morning and evening services of the Church of England and the two services and sermons on Sundays. It is likely that many or most of the men summoned to meet as a General Assembly had probably attended the morning service that day and watched and listened as Richard Bucke, the minister, read from his copies of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. Precisely which words he read and the men and women assembled in the church heard is unclear. The Latin, Greek, and Hebrew texts had been translated by then into several English-language editions of the Bible, each with subtle and sometimes significant differences in tone and meaning. Bucke probably had a copy of what was called the Geneva Bible, which was likely the English version most widely used at the beginning of the seventeenth century and the edition that the church’s reformers, known as Puritans, preferred. The Virginia Company’s shareholders and officers included many Puritans, and several of the colony’s early clergymen, including Bucke, were sympathetic to the Puritans. Bucke might possibly have had a copy of the new translation of the Bible, the one that King James had commissioned not long before he issued the first charter to the Virginia Company in 1606 and that was published in 1611, not long after Bucke first stepped ashore in Virginia and walked among the starving men in Jamestown.

Directions printed in Bucke’s copy of the Book of Common Prayer required that he read the service and the words of Scripture distinctly and with a loud voice that the people might hear, that none by virtue of being unlettered remain ignorant of the word of God. The words that he read would have been familiar to the people in the church. The services of the church were so arranged that the same significant texts were read aloud once each year and the psalms once in every month, “that the people (by daily hearing of holy scripture read in the Churche),” according to the explanatory preface in the 1559 Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer, “shoulde continually profite more and more in the knowledge of God, & be the more enflamed with the love of his true religion.”3

If Bucke conducted the full morning service for the thirtieth of July, the first of the three psalms for the day was Psalm 144, which began, in the words of the Geneva Bible, “Blessed be the Lord my strength, wc teacheth mine hands to fight, & my fingers to battel. He is my goodness & my fortres, my tower & my deliverer, my shield, and in him I trust, which subdueth my people under me.”4 Those words may have carried a special significance that morning to the men who gathered in the church in that little town on the bank of a great river on the edge of a vast continent that contained no more than a few hundred Protestant Christians. They needed all the earthly help and divine aid that they could get. The psalm concluded with the prayer “That our corners may be ful, and abunding with divers sortes, and that our shepe may bring forthe thousands, and tens thousands in our stretes: That our oxen may be strong to labour: that their be none invasion, nor going out, nor no crying in our stretes. Blessed are the people, that be so, yea, blessed are the people, whose God is the Lord.”

Those words of the psalmist must have resonated in the souls of the men in the church that day. They needed moral and spiritual support to make a reality of their dreams of peace, full storehouses, and plentiful flocks. One wonders what Richard Bucke thought about those words. He had been shipwrecked en route to Virginia in 1609 (in the storm that suggested to William Shakespeare the plot for the Tempest) and had been in the first ship to reach Jamestown in May 1610 at the end of the starving winter. His wife died. It is possible that he married a second time and that his second wife died, also. He named his children Mara (meaning bitter), Gershon (expulsion), Peleg (division), and Benoni (sorrow), and Benoni was feeble-minded.5 Bucke’s life in Virginia was hard, but that was one of his bonds with every other man and woman who entered the church then or any other day.

Bucke then read the two passages from Scripture prescribed for that day. From chapter 8 of the book of Jeremiah, he read about how the kings and people of Judah had sinned and ignored God’s warnings and how as a consequence their bones were taken out of their tombs and spread “as dung upon the earth.” In the third verse were the words of warning that would have made any one who recalled or knew about the starving time in Virginia shudder: “And death shalbe desired rather then life of all the residue that remaineth of this wicked familie, which remaine in all the places where I have scatred them, saith the Lord of hostes.” Bucke then read from chapter 18 of the book of John about the arrest of Jesus in the garden, how Peter thrice denied him, how Jesus denied that he was a mere earthly king, and how Pilate prepared to hand Jesus over to the Jews for trial and execution.

The lessons that day, for both the lettered and the unlettered, reminded men and women of their duty to obey God and to avoid sin, to recognize Jesus as a greater king than an earthly king, and that even earthly kings were subject to the word of God through the words of Jesus. To the people in the church in Jamestown that day, the words in the psalm about subduing “my people under me” meant not only the unchristianized and possibly dangerous Indians, they also meant all of the men and women, all of the people who were free and those who were bonded by indenture to labor for other people or for the company. Except the king, every soul was under some other person’s temporal and spiritual authority.

Later that morning Bucke met in the church with the governor, councilors, company officers, and other men when they assembled as the first General Assembly of Virginia. The report of the meeting records that “forasmuche as mens affaires doe little prosper where Gods service is neglected,” Bucke offered a prayer “that it would please God to guide & sanctifie all our proceedings, to his owne glory, and the good of this plantation.”6 The assembly members conducted their secular business as if with God’s eyes watching over their shoulders.

The eyes of the king and the officers of the Virginia Company were also looking over their shoulders. Perhaps, too, residents of the town peered in at the church windows or stood inside or sat on the benches in the church to watch and listen. The official report of the proceedings of that and the succeeding four days does not mention Jamestown’s residents. The eyes of God, king, and company were doubtless of much more concern to the members of the assembly than the eyes and ears of the people. If the men and women who lived in Jamestown were watching and listening and not busy working in thei...