![]()

PART I

CONCEPTION

This first part of the present work invites readers to question the nature and the purpose of the research they wish to undertake. The explicit and implicit choices they make will be affected by the type of research they want to do and the way they want to do it. One important question researchers must answer concerns their conception of the reality of the management phenomena they wish to study. If this is an objective reality, they will need to develop and choose appropriate measuring instruments to study it. But it may be a constructed reality, its existence dependent on the subjectivity of the researcher – an elusive reality that transforms and slips out of our grasp just as we think we are drawing close to it. After answering this first question, the subject of their research must be defined: what they are setting out to study. But here again, the answer is not as simple as we might wish. We show that the research subject is constructed and not, except artificially, given. It fluctuates, reacts and is contingent upon the conception of the research process and how this process unfolds. Once the subject has been defined, researchers are faced with the choice as to what they want to achieve. There are two main directions to take. The first consists of constructing a new theoretical framework from, among other things, their observations. The second is to test a theory; to compare it with empirical observations. Researchers will also have to decide on an approach, either qualitative or quantitative, or perhaps a mixture of the two, and on the type of data they will need to collect: decisions that must be congruent with the aim of their research. Finally, researchers have to decide how they will attack their research question: whether to study content (a state) or to study a process (a dynamics). The methodologies used will differ according to the choices they have already made. It is vital for researchers to give careful consideration, and as early as possible, to these questions of the nature, the aim and the type of research they want to undertake, and the empirical sources available to them or which they wish to use.

![]()

1

EPISTEMOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

Martine Girod-Séville and Véronique Perret

Outline

All research work is based on a certain vision of the world, employs a methodology, and proposes results aimed at predicting, prescribing, understanding or explaining. By recognizing these epistemological presuppositions, researchers can control their research approach, increase the validity of their results and ensure that the knowledge they produce is cumulative.

This chapter aims to help the researcher conduct this epistemological reflection, by providing the tools needed to answer the following three questions: How is knowledge generated? What is the nature of the produced knowledge? What is the value and status of this knowledge? In answering these questions, inspiration may be drawn from the three major epistemological paradigms usually identified with organizational science: the positivist, the interpretativist, and the constructivist paradigms. From this researchers can evaluate the scientific validity of their statements and reflect on the epistemological validity and legitimacy of their work. Consideration of such questions can help researchers to elaborate their own positions in relation to the epistemological pluralism present in organizational science.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge, and so of science: the study of its nature, its validity and value, its methods and its scope. Epistemological questioning is vital to serious research, as through it researchers can establish the validity and legitimacy of their work. All research is based on a certain vision of the world, uses a certain method and proposes results aimed at predicting, prescribing, understanding, constructing or explaining. Recognizing that they have these presuppositions allows researchers to control their research approach, to increase the validity of the knowledge produced and to make this knowledge cumulative. Epistemology is, therefore, consubstantial with all research.

In this chapter, we invite researchers wanting to establish the legitimacy of their work to examine their research approach by posing the following three questions:

What is the nature of the knowledge we can generate through our research? Before we can embark on a quest for new knowledge, we have to ascertain clearly what it is we are looking for. Will such knowledge be objective? Will it be an accurate representation of a reality that exists independently of our experience or understanding of it? Or will it be our particular interpretation of reality? Is such knowledge a construction of reality? We encourage researchers to question their vision of the social world – to consider the relationship between subject and object.

How can we generate scientific knowledge? Are we to generate new knowledge through a process of explanation, understanding or construction? In asking this we are questioning the path we take to gain knowledge.

What is the value and status of this knowledge? Is the knowledge we generate scientific or non-scientific? How can we assess this? How can we verify and corroborate our new knowledge? Is it credible and transferable? Is it intelligible and appropriate? Through questioning these criteria we can evaluate the knowledge we produce.

To answer these questions, researchers can draw inspiration from the three major paradigms that representing the main epistemological streams in organizational science: the positivist, interpretativist and constructivist paradigms. According to Kuhn (1970), paradigms are models, intellectual frameworks or frames of reference, with which researchers in organizational science can affiliate themselves. The positivist paradigm is dominant in organizational science. However, there has always been a conflict between positivism and interpretativism, which defends the particularity of human sciences in general, and organizational science in particular. Constructivism, meanwhile, is becoming increasingly influential among researchers working in organizational science.

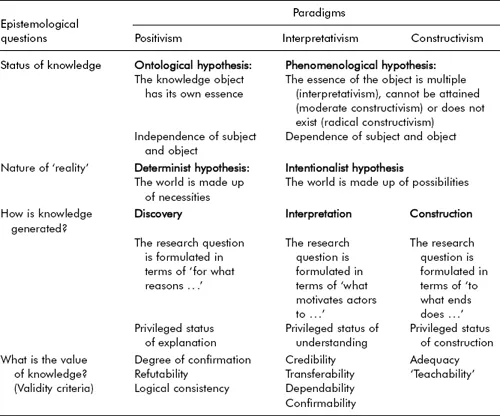

Constructivism and interpretativism share several assumptions about the nature of reality. However, they differ in the particular ideas they express about the process of creating knowledge and the criteria with which to validate research. As we will see further on, the aim of positivism is to explain reality, whereas interpretativism seeks, above all, to understand it and constructivism essentially constructs it. The answers given to different epistemological questions by each of the paradigms are summarized in Table 1.1.

In the rest of this chapter we will concentrate on explaining the different positions taken by each of the paradigms vis-à-vis the nature of the knowledge produced, the path taken to obtain that knowledge and the criteria used to validate the knowledge. This discussion will lead on to an inquiry into the existence of epistemological pluralism, which we will look into further in the final part of the chapter.

SECTION 1 WHAT IS KNOWLEDGE?

Before we can give due thought to the question of what knowledge is, we must first consider the related question of the nature of reality. Does reality exist independently of the observer, or is our perception of reality subjective. What part of ‘reality’ can we know?

Table 1.1 Epistemological positions of the positivist, interpretativist and constructivist paradigms

1. A Positivist Understanding of Reality

For positivists, reality exists in itself. It has an objective essence, which researchers must seek to discover. The object (reality) and the subject that is observing or testing it are independent of each other. The social or material world is thus external to individual cognition – as Burrell and Morgan put it (1979: 4): ‘Whether or not we label and perceive these structures, the realists maintain, they still exist as empirical entities.’ This independence between object and subject has allowed positivists to propound the principle of objectivity, according to which a subject’s observation of an external object does not alter the nature of that object. This principle is defined by Popper (1972: 109): ‘Knowledge in this objective sense is totally independent of anybody’s claim to know; it is also independent of anybody’s belief, or disposition to assent; or to assert, or to act. Knowledge in the objective sense is knowledge without a knowing subject.’ The principle of the objectivity of knowledge raises various problems when it is applied in the social sciences. Can a person be his or her own object? Can a subject really observe its object without altering the nature of that object? Faced with these different questions, positivist researchers will exteriorize the object they are observing. Durkheim (1982) thus exteriorizes social events, which he considers as ‘things’. He maintains that ‘things’ contrast with ideas in the same way as our knowledge of what is exterior to us contrasts with our knowledge of what is interior. For Durkheim, ‘things’ encompasses all that which the mind can only understand if we move outside our own subjectivity by means of observation and testing.

In organizational science, this principle can be interpreted as follows. Positivist researchers examining the development of organizational structures will take the view that structure depends on a technical and organizational reality that is independent of themselves or those overseeing it. The knowledge produced by the researcher observing this reality (or reconstructing the cause-and-effect chain of structural events) can lead to the development of an objective knowledge of organizational structure.

In postulating the essence of reality and, as a consequence, subject–object independence, positivists accept that reality has its own immutable and quasi-invariable laws. A universal order exists, which imposes itself on everything: individual order is subordinate to social order, social order is subordinate to ‘vital’ order and ‘vital’ order is subordinate to material order. Human beings are subject to this order. They are products of an environment that conditions them, and their world is made up of necessities. Freedom is restricted by invariable laws, as in a determinist vision of the social world. The Durkheimian notion of social constraint is a good illustration of the link between the principle of external reality and that of determinism. For Durkheim (1982), the notion of social constraint implies that collective ways of acting or thinking have a reality apart from the individuals who constantly comply with them. The individual finds them already shaped and, in Durkheim’s (1982) view, he or she cannot then act as if they do not exist, or as if they are other than what they are.

Consequently, the knowledge produced by positivists is objective and a-contextual – in that it relates to revising existing laws and to an immutable reality that is external to the individual and independent of the context of interactions between actors.

2. A Subjective Reality?

In the rival interpretativist and constructivist paradigms, reality has a more precarious status. According to these paradigms, reality remains unknowable because it is impossible to reach it directly. Radical constructivism declares that ‘reality’ does not exist, but is invented, and great caution must be used when using the term (Glasersfeld, 1984). Moderate constructivists do not attempt to answer this question. They neither reject nor accept the hypothesis that reality exists in itself. The important thing for them is that this reality will never be independent of the mind, of the consciousness of the person observing or testing it. For interpretativists, ‘there are multiple constructed realities that can be studied only holistically; inquiry into these multiple realities will inevitably diverge (each inquiry raises more questions than it answers) so that prediction and control are unlikely outcomes although some level of understanding (verstehen) can be achieved’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985: 37). Consequently, for constructivists and interpretativists, ‘reality’ (the object) is dependent on the observer (the subject). It is apprehended by the action of the subject who experiences it. We can therefore talk about a phenomenological hypothesis, as opposed to the ontological hypothesis developed by the positivists. The phenomenological hypothesis is based on the idea that a phenomenon is the internal manifestation of that which enters our consciousness. Reality cannot be known objectively – to seek objective knowledge of reality is utopian. One can only represent it, that is, construct it.

Subject–object interdependence and the rebuttal of the postulate that reality is objective and has its own essence has led interpretativist and constructivist researchers to redefine the nature of the social world.

For interpretativists and constructivists, the social world is made up of interpretations. These interpretations are constructed through actors’ ‘interactions, in contexts that will always have their own peculiarities. Interactions among actors, which enable development of an intersubjectively shared meaning, are at the root of the social construction of reality’ (Berger and Luckman, 1966).

The Social Construction of Reality

Sociological interest in questions of ‘reality’ and ‘knowledge’ is thus initially justified by the fact of their social relativity. What is ‘real’ to a Tibetan monk may not be ‘real’ to an American businessman. The ‘knowledge’ of the criminal differs from the ‘knowledge’ of the criminologist. It follows that specific agglomerations of ‘reality’ and ‘knowledge’ pertain to specific social contexts, and that these relationships will have to be included in an adequate sociological analysis of these contexts … A ‘sociology of knowledge’ will have to deal not only with the empirical variety of ‘knowledge’ in human societies, but also with the processes by which any body of ‘knowledge’ comes to be socially established as ‘reality’ … And insofar as all human ‘knowledge’ is developed, transmitted and maintained in social situations, the sociology of knowledge must seek to understand the processes by which this is done in such a way that a taken-for-granted ‘reality’ congeals for the man in the street. In other words, we contend that the sociology of knowledge is concerned with the analysis of the social construction of reality … Society is indeed built up by activity that expresses subjective meaning. It is precisely the dual character of society in...