![]()

1

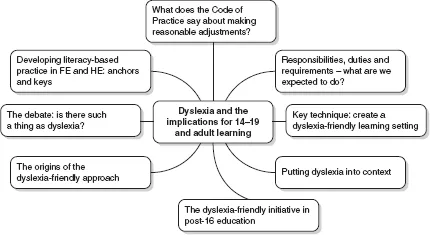

Dyslexia and the implications for 14–19 and adult learning

Chapter overview

® 2008 with express permission from Mindjet, LLC. All rights reserved.

Responsibilities, duties and requirements – what are we expected to do?

The provision of a state education system is an act of social engineering based on social and political beliefs that the intervention offered therein will improve quality of life, both for individuals and for society as a whole. Underpinning this is a conception of society which may or may not be questioned by educators themselves. Currently, educational function in the UK is focused on the targets of developing expertise in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and on employability and entrepreneurship, supporting a vision of an economy based upon the generation and development of ideas and knowledge.

Policies and guidance underpin this movement, promoting lifelong learning and widening participation. For learners with difficulties and/or disabilities, the world of education has duties to provide access and to promote equality of opportunity. Included within these are the duty to make special adjustments and the duty not to treat disabled people less favourably, even to the point of treating learners with disabilities and difficulties more favourably (DRC, 2005: 23).

In the UK, the 2001 SEN and Disability Act amended the Disability Discrimination Act of 1995, becoming Part IV of that Act, thereby extending the DDA 1995 to include provisions for education. A further statutory instrument, which carries the same legal obligation as the Act itself, brought in regulations for further and higher education in 2006. These legislativ provisions bring the UK in line with the European Employment Framework Directive (DRC, 2007: iv), contributing to a suite of initiatives, policies and legislative actions, intended to lead towards employability and employment for a wider population. Added to this is the continuing importance of literacy; accordingly dyslexia has gained an increasingly higher profile.

The trend towards a changing population in FE and HE is not without resistance. It may therefore come as a surprise to some that legislation and policy have firmly settled on the side of learners with difficulties and/or disabilities. For many people, when, or if, they think about disability, it is with a view to treating students ‘fairly’. However, this is not only incorrect, it is dangerous for institutions.

From time to time the popular media may carry accusations of unfairness when adjustments are made to take account of disability, especially in the case of dyslexia. This is particularly so when the argument is directed against learners who seem to be unfairly advantaged, perhaps because their dyslexia is towards the milder end of the range, as is frequently the case in HE. This is because the concepts of social justice, upon which reasonable adjustments are based, are not widely understood. These concepts are founded upon earlier ideas about the politics of recognition and the politics of distribution. The origins of these may be attributed to Rawls’ work in considering justice through distribution (first principle) and then advantageous redistribution (second principle) in A Theory of Justice (Rawls, 1971), to Taylor’s work (‘The politics of recognition’ 1974) and to Honneth’s work on the concept of justice through recognition, which could itself include redistribution (see for example Honneth, 2004). These concepts focus on how goods and resources are distributed throughout society in order to ensure more equitable treatment. They may include ideas about ‘fair shares’, ‘level playing fields’ and the redistribution of resources through policies and taxes. These ideas do not necessarily trouble existing locations of power and resources. However, the recognition concept goes further, it includes identity politics, and is expressed here through the perspective of making special arrangements and particular adjustments in favour of disadvantaged people; in this case, people experiencing dyslexia.

There should be no doubt that present-day policy, practice and legislation are oriented around the politics of recognition. Anything else operates against disadvantaged groups and individuals; fair shares are not fair when one sector of the population is disadvantaged already. However, there are other challenges of unfairness in the popular perception of dyslexia. These come from the continuing scepticism that surrounds dyslexia, which has its origins in the lack of certainty about what dyslexia is, or might be, how we understand and describe it and how we assess it.

Putting dyslexia into context

The understanding of dyslexia continues to develop and evolve, yet the dyslexia debate continues, with no definition currently in existence that completely satisfies all interested parties. This is partly as a result of the different discourses within dyslexia, both psychological and sociological, and partly because there is, as yet, no complete agreement as to the nature of dyslexia. Denials of dyslexia generally turn out to be challenges to the way dyslexia is discussed or assessed. In consequence, there is no guarantee that discussions about dyslexia are considering the same factors. Contributing to this disparity is the fact that there are views of dyslexia that consider it to be a cause, while others see it as an effect.

A fundamental issue in dyslexia remains that of whether dyslexia is a separate entity, a characteristic that exists in some learners and not in others, or whether it is the expression of the extreme end of the range of difficulty in acquisition of literacy skills. The latter argument might merge with the former by considering whether there may be a point in this range where the difficulty becomes so extreme that it can be identified as a characteristic in its own right. However, this view would need to be explored further.

A further key issue is the point that conceptualisations of dyslexia are so wide and varied that they seem not to be describing one particular phenomenon. Consequently for some, ‘dyslexia’ might now be understood as an umbrella term, while others focus upon subtypes (about which there is also a lack of strong agreement) or upon consideration of whether the main dyslexia theories can be reconciled.

Regardless of the conceptualisation of dyslexia, there is no doubt that for some people, the skills of literacy acquisition are very difficult, to the extent that they may consider themselves, or be considered by others, as illiterate. It is also clear that this difficulty is particularly resistant to standard teaching and learning for literacy, but may also be both unusual and striking in terms of other skills and potential for learning that a person might have. Discussions continue as to whether other characteristics, such as creativity or practical ability, are associated with dyslexia in any firm way.

Whether it is conceptualised as a disability, difficulty or difference, dyslexia is a hidden characteristic, and the time and effort spent on checking, double-checking and correcting by people who experience dyslexia is not noticed by others and therefore not respected or understood. Further, the support now available to dyslexic learners in FE and HE may be viewed simplistically as compensating for dyslexia, so that it effectively disappears. This is not the case. Dyslexia continues, and while many learners overcome their difficulties brilliantly, this still requires time, effort and practice, and causes additional fatigue.

The education system attempts to provide a safety net, recognising the increasing importance of literacy in the modern world. In addition, a reconsideration of the developmental process of learning as embodied in the Lifelong Learning initiative now supports the view that it is never too late to learn. So, while it is unlikely that a person with severely reduced literacy skills will be studying in HE, there may be students whose higher level literacy skills were acquired later in their lives, and who have taken advantage of Access programmes. Additionally, FE colleges and independent providers of work-based training may find, within their intake, learners with only a rudimentary level of literacy. For some students their literacy difficulty is likely to be the result of unidentified dyslexia.

The origins of the dyslexia-friendly approach

The British Dyslexia Association’s (BDA) dyslexia-friendly initiative in local authorities and schools, launched in 1999, received a positive response. Five years later, it was followed by a quality mark process aimed at local authorities. The dyslexia-friendly approach did more than move the focus of provision into schools; it included the environmental aspects of the learning setting, by seeking to make learning more accessible to children and young people experiencing dyslexia. It also caught the mood of the ethical and philosophical change that was pervading education through increasing awareness of the social rights model of disability. The social model supports the view that while an individual may experience impairments, it is the social situation, both practical and attitudinal, that is disabling.

The dyslexia-friendly approach does not take an individual-deficit focus, and this may present some difficulties to people who prefer such a view. The dyslexia-friendly approach places the emphasis upon creating a learning setting, from the top down, that is sensitive to the learning requirements in dyslexia. It includes the belief that effective teaching for learners with dyslexia is effective teaching for all learners with special educational needs, learning difficulties and/or disabilities. Much of the initiative is concerned with creating a supporting ethos with an inbuilt expectation that this will develop and grow, pervading the whole learning setting. This expectation extends to elements in the infrastructure, including those within local authority policy and practice.

The dyslexia-friendly initiative in post-16 education

The dyslexia-friendly approach expects that what is good for dyslexic learners is good for all learners. The possibility of gaining the BDA’s dyslexia-friendly quality mark has now been extended to FE colleges and college departments, and to independent trainers and providers, transferring dyslexia-friendly principles to the post-16 setting. The mission statement for FE is:

To promote excellent practice by the college as it carries out its role of supporting and challenging its staff to improve accessibility for more learners. (BDA, n.d.)

For practitioners this includes sharing good practice and encouraging colleagues to review their practice in the classroom. This removes inherent barriers to learning and thereby increases the opportunities for learners with specific learning difficulties, including dyslexia, to achieve their educational goals.

The FE and training provider protocols are very similar. As with the LA Quality Mark process, the institution or department assesses its dyslexia-friendly characteristics against four categories: focusing, developing, established and enhancing. The process is comprehensive, addressing pre-determined standards in the following five areas:

- the effectiveness of the management structure

- the identification of dyslexia/SpLD

- the effectiveness of resources (physical environment, teaching and learning)

- continuing professional development

- partnership with learners, parents or carers and external agencies.

These are matched against the development criteria. Guidance from the BDA clarifies these, confirming that the meaning of ‘focusing’ is that an area requiring further development has been identified; ‘developing’ indicates that work in the relevant area is progressing; ‘established’ means that identified dyslexia-friendly processes are taking place as standard; and ‘enhancing’ means that practice that is taking place beyond the level required...