![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Child Development and Early Years Education

This is a particularly exciting time to be writing this book. To begin with, and perhaps most fundamentally, it is an exciting time to be involved in early years education. For many years, the education of our youngest children has been a neglected and massively under-funded cottage industry, made up mostly of enthusiastic amateurs working in largely voluntary or very poorly paid capacities and working in church halls, scout huts and the like. Suddenly, and perhaps too suddenly in some ways, not only in the UK, but internationally, in the developed world, the developing world, and increasingly even in the least well-developed countries in the world, early years education is being taken seriously and is enjoying unprecedented levels of investment and development. The sheer speed of these developments is currently presenting major challenges, but there can be no doubt that this new recognition is long overdue and enormously important. All of us involved in early years education at this time have an exciting opportunity to contribute very significantly to the transformation of this, the most important phase of a child’s education, into a professional, evidence-based enterprise which can make a real difference to the quality of children’s lives, and to the societies into which they grow up as citizens.

At the same time, there is equally exciting progress in developmental psychology. We are currently experiencing a massive leap forward in our understandings about young children’s development which, as is often the case with scientific advance, is largely a consequence of new technologies. So, just as it is accepted in astronomy that Galileo’s most important contribution was in his development of the telescope, rather than his ideas about the Earth travelling around the Sun, so in developmental psychology, the emergence of an array of new methodological tools has been of enormous benefit. As we shall see as we review the various kinds of evidence later in the book, these have included the use of video, of computers, of non-invasive neuroscientific methods, of techniques developed in evolutionary biology, and of a range of new research designs and methods of analysis. All of these technological and methodological advances have enabled us to increase enormously what we know and understand about young children. Most importantly, they have contributed to a revolution in developmental psychology. When I trained as a psychologist in the late 1960s and early 1970s, much of the research with young children was methodologically limited and tended towards a deficit model of the young child, focusing on what they could not do. By contrast, the more sophisticated approaches of modern developmental psychology have enabled researchers to uncover a wealth of information about all the astonishing early achievements of the young child.

So, to be writing a book at this time, which attempts to distil what we currently know from developmental psychology that might be helpful in our attempts to introduce young children to the world of education, is a delight and a challenge. It is a challenge because of the wealth of knowledge we now possess about young children’s capabilities, but it is a delight because the book can focus so clearly on what children can do, rather than on their limitations.

Focusing on what children can do is, however, more than simply a pleasing, self-indulgent emotional response. It is actually enormously important in relation to early childhood education. As humans we have evolved, mostly in the Pliocene period when we lived for several million years as hunter-gatherers, to learn and develop in particular ways. These early adaptive processes have fashioned the human brain to be enormously efficient at processing information, but it achieves this in particular ways, which have made us astonishingly brilliant at some tasks (such as remembering faces, learning language, learning from one another), but rather poor at others (such as remembering names, understanding physics, working out how our latest gadget works by reading the manual). In the strange modern world in which we now find ourselves, we need to be aware of how our brain has evolved to learn and develop, so that we can build on our strengths as a species, rather than exposing our weaknesses. One of my earliest pieces of published writing about young children’s learning concerned their learning of mathematics (Whitebread, 1995). In that chapter, I argued that understandings of how young children learn, derived from modern developmental research, showed us why traditional methods of teaching mathematics (abstract, removed from meaningful contexts, using conventional written symbols and taught algorithms) were likely to be generally ineffective and undermine children’s confidence. With a better informed approach (practical, placed in meaningful contexts, building on children’s own representations and strategies), we could harness the strengths of human learning and help children to become confident and able young mathematicians. This book is an attempt to extend this kind of approach to the much broader sweep of children’s development and learning.

Developing Children as ‘Self-regulating’ Learners

Indeed, the guiding principle and fundamental theme of the book is that young children can, with benefit to themselves as learners and developing individuals, do more for themselves than has previously been thought or commonly provided for in educational settings. They can take responsibility for their learning and ownership of it, and derive enormous benefit from doing so. They can become what is referred to in the developmental literature as ‘self-regulating’ learners. This is a theme which runs through each chapter of this book, as it relates as much to children’s emotional and social development as it does to the development of their intellectual capacities. In the final chapter of the book, however, it is the central focus and works to bring together the principles and implications for pedagogy derived from the various aspects of children’s development covered in the intervening chapters.

There is currently widespread interest and enthusiasm in the early years world for fostering self-regulating or ‘independent’ learning among young children, as attested by a number of publications (Featherstone and Bayley, 2001; Williams, 2003), by the current enthusiasm for such approaches as Reggio Emilia and High/ Scope, both of which emphasise children’s autonomy and ownership of their learning, and by recent official government guidelines. Recent initiatives, circulars and curriculum documents from various government agencies have offered a range of suggestions as to what independent or self-regulated learning might involve. In the revised QTS Standards entitled Qualifying to Teach (TDA, 2006), for example, teacher trainees are required under Standard S3.3.3 to:

teach clearly structured lessons or sequences of work which interest and motivate pupils and which make learning objectives clear to pupils … [and] promote active and independent learning that enables pupils to think for themselves, and to plan and manage their own learning.

In the Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage (DfEE/QCA, 2000), which established the new curriculum for children between 3 and 5 years of age, one of the stated ‘Principles for early years education’ is that there should be:

opportunities for children to engage in activities planned by adults and also those that they plan and initiate themselves. (p. 3)

Of course, as is often the case with these kinds of policy documents, these are simply statements of well-established good practice rather than anything startlingly new (despite the attempts of politicians to present them as such, with the implication that they personally have come up with a brilliant new idea that, somehow, has eluded the entire teaching profession). While a commitment to encouraging children to become independent or self-regulating learners is very common amongst early years teachers, however, at the level of everyday classroom realities, there are a number of problematic issues. The need to maintain an orderly classroom, combined with the pressures of time and resources, and teachers’ perceptions of external expectations from headteachers, parents and government agencies, can often militate against the support of children’s independence. This is unfortunate and often counter-productive. The kind of overly teacher-directed style this tends to engender may create an impression of having ‘covered’ the curriculum, but is largely ineffective in promoting learning in young children, and does not help at all in the larger project of developing children’s ability and confidence to become independent learners.

I remember very vividly, for example, my own two children’s experiences with pre-school groups. At one group they attended, which claimed to teach the children to read, write, etc. and which had quite a long waiting list, they were greeted at the door and directed to the table at which they should sit, where materials were already neatly arranged and ready for some pre-designed craft activity. Here, they were told not to touch anything until the adult helper took them through each stage of the process, often helpfully re-adjusting things that proved too difficult for them to achieve. After 20 minutes, all the children at the table had produced identical robots, Mother’s Day cards or whatever and they moved on to the next table where another activity was already waiting for them. The children made few if any choices, were never required or encouraged to have their own ideas, and had an almost entirely seat-based experience. At the end of the morning, they rushed up to greet me (or my wife), and usually forgot to bring with them any of the perfect creations they had been rather peripherally involved in. At a second pre-school (well, at the time, it was actually called a playgroup), for which, ironically, there was much less parental demand (probably as no claims were made about the formal learning of literacy), the children arrived to find a whole array of possible play activities from which they could choose, including some seat-based craft-type activities, but also construction materials, sand and water trays, bikes and other vehicles, a dressing-up rail, a ‘home’ corner for imaginative play, and so on. At the end of the morning, they would rush up enthusiastically, usually dressed up as Princess Smartypants or Wonder Woman, to show us two bits of cornflake packet stuck together with sellotape which was their magic helicopter or new little puppet friend Margaret, and which had to be carefully held onto so they could finish it at home, and then they had to be persuaded to transform themselves back into children and leave so that the nice ladies could tidy everything away until tomorrow. You can probably tell by the way I have written about these two establishments where I thought our children were doing some real learning. It was in the playgroup, of course, where they were being properly challenged, where what they could do was being recognised and built upon, and where they were learning not only practical, cognitive and social skills, but also how to make choices, develop their own ideas, and manage and regulate their own learning.

On top of the current constraints and difficulties pushing early years practitioners away from play-based and towards more adult-directed and formal approaches, there is also, understandably, often a lack of clarity as to the nature of independent or self-regulating learning. It is clear from governmental policy statements, as I cited above, that there is currently a strong commitment to the area of independent learning. However, there is also confusion and a need for clear definition. To begin with, while on the one hand early years practitioners are being asked to provide ‘personalised learning’ and respond to the ‘Every Child Matters’ agenda, at the same time they are being continually bombarded by ‘top-down’ pressures to force-feed all their great variety of children with set curricula and formalised ‘standards’. In some recent policy guidelines (such as the recent Early Years Foundation Stage [DfES, 2006] document) and commentaries, furthermore, the emphasis has unhelpfully shifted more towards helping children with personal independence skills and in becoming an independent pupil, i.e. being able to function in a classroom without being overly dependent on adult help. This is quite distinct, however, from the concern to help children develop as independent learners, i.e. being able to take control of, and responsibility for, their own learning. It is for this reason that the term ‘self-regulation’ is increasingly preferred, with its emphasis on the learner taking control and ownership of their own learning. As we shall see, it is also a term which has a strong tradition within the developmental psychological literature.

Over the last few years, I have worked with 32 Cambridgeshire early years teachers on the Cambridgeshire Independent Learning (C.Ind.Le) Project (Whitebread and Coltman, 2007; Whitebread et al., 2005). This research has established that young children in the 3–5 age range, given the opportunity, are capable of taking on considerable responsibility for their own learning and developing as self-regulated learners, and that their teachers, through high-quality pedagogical practices, can make a highly significant contribution in this area. (More detail about this research is provided in the final chapter of this book.) The findings which have been derived from the C.Ind.Le project, and other similar research, however, have been a large part of the inspiration to write this book, and permeate each chapter.

The Impact and Nature of Quality in Early Years Education

Developing the educational provision for our youngest children is, of course, of vital importance. It is now well established that a child’s educational experience in the early years has both immediate effects upon their cognitive and social development and long-term effects upon their educational achievements and life prospects. Sylva and Wiltshire (1993) reviewed a range of evidence which supports this position. This evidence includes studies of the Head Start programmes in the USA, the Child Health and Education Study (CHES) of a birth cohort in Britain and Swedish research on the effects of day care.

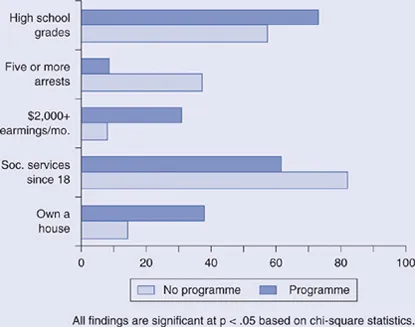

To begin with, these various studies appeared to produce inconsistent findings. Early studies of the Head Start programmes, for example, which provided pre-school places for children in economically and socially disadvantaged areas in the USA, suggested immediate cognitive and social gains, but little lasting effect. The CHES study, on the other hand, found a clear association between pre-school attendance and educational achievements at age 10. More recent analysis, however, has revealed that lasting long-term effects are dependent upon the quality of the early educational experience. Sylva and Wiltshire (1993) noted particularly the evidence of long-term impact achieved by High/Scope and other high-quality, cognitively orientated pre-school programmes. The most famous of these programmes was the Perry Pre-school Project in Ypsilanti, Michigan, directed by David Weikart, which was part of the Head Start initiative and later developed into what is now known as the High/ Scope programme. Figure 1.1 presents some of the results from a follow-up study he conducted with a colleague with a cohort of 65 children who had attended this half-day educational programme over two years during the mid-1960s. Their outcomes at age 27 were compared to a control group of children from the same neighbourhood who had not attended the pre-school programme. As we can see, as well as achieving significantly better high school grades, the children who had attended the pre-school programme had been arrested on significantly fewer occasions, had higher earnings, had needed to receive less support from social services, and were much more likely to own their own house (Schweinhart et. al., 1993).