![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

(Daly, 1986: 113)

I often meet people interested in counselling who say, ‘I’m not a feminist but…’ They then go on to reveal an interest in just the kinds of ideas explored in this book. The idea of gender equality has now become main-stream, at least in most Western societies. But equality is a complex issue and requires deep shifts in our whole approach to life as well as the more obvious economic and social changes that are rapidly taking place. In spite of these we are still living in a male-defined world to which women have adapted brilliantly. Many women are far more fulfilled in this world than in the sexist one of the past. Yet we don’t all agree with the values of a society where business reigns supreme and parenting comes bottom of its priorities. A world fully based on equal valuing of the ‘feminine’ would be dramatically different from the one we have today.

Equality between any different groups or individuals does not mean sameness. So what does it mean? It must mean working towards narrowing economic gaps between rich and poor, equal opportunities, equal rights, mutual respect, etc. But I also believe it means a complete trans-formation of the underlying patterns/structures of thought that run our lives. We need to move from hierarchical patterns to equarhythmic ones, which change constantly from one opposite to another. Equarhythms are in the process of equalizing, balancing all the time just as in nature and in our bodies. In this book we look mainly at the psychological aspects of these processes. This rhythm model can be described as ‘feminine’ (see discussion on p. 3) but it can be developed by men as well as women and fits better with our post-modern world than the old win/lose, hierarchical models (Chaplin, 1998).

This book is however focused on gender and on the experience of women. It tries to weave together some of the different strands of feminism that have at times opposed each other. Firstly there is an acknowledgement of the way in which gender is socially constructed. Girls learn to be girls, both from their mothers and from the wider society (Chodorow, 1978). Secondly there is the view that women in general have particular advantages for example in our intuition, sexuality and spirituality that need to be valued more by society (Irigaray, 1985). Goddess spirituality tends to this approach (Chaplin, 1993). Thirdly there is the valuing of the ‘creative feminine’ (Kristeva, 1987) in contrast to ‘masculine’ rationality which is not confined to female bodies. Some Jungians take this approach too. Fourthly there is a post-modern approach (Flax, 1990) that emphasizes the fluidity of identities and categories including those of gender. I find that all these approaches are useful, in different contexts, perhaps even in different phases of an individual or group process.

This first chapter is a general introduction to the basic concepts involved in feminist counselling as I understand and practise it. Chapter 2 deals with some of the initial aspects of the counselling process: Who comes? How does a counsellor reach potential clients? Where do we work? How do we charge? What do we say at the very first meeting?

The rest of the book follows seven typical phases of a counselling cycle, each chapter covering one aspect. In my experience, not all clients move through all seven phases within the same counselling contract of, say, a year with one counsellor. It may take them many years to go through the cycle, or it may take just a few weeks. They may use several different counsellors, workshops or ‘spiritual’ guides during their growth cycle. And most people seem to go through many cycles during their lifetime.

At the same time, however, the different elements of each phase may recur in later phases, being woven together as people change and develop. Clients rarely move in straight lines from 1 to 7, but because making books is a somewhat linear form of expression, I have presented the stages as a sequence of chapters. I have not separated theory and practical aspects in a linear way, but woven them together throughout the book, to show how they interconnect.

In addition to exploring the theory and practice of each phase of counselling, I also describe the cycles of three specific clients. These are all women, although in my experience men seem to move through the same phases and share many of the issues that women have to face. But some specific issues affect women differently from men. The emphasis in this book is on women’s development process, although male clients are mentioned from time to time. The three example clients are from different class backgrounds, begin heterosexual and are fairly representative of the range of clients likely to come for counselling in any country where it is available. In my experience with black and white clients from several different cultures, the same kinds of general human issues seem to be important to everyone. However there are specific issues that relate to particular cultures and not to others. There are also issues around racism that affect black clients differently from white clients. However these particular kinds of differences and their effects on the counselling process are described in another book in this series (d’Ardenne) and will not be explored in detail here. Yet I am aware that as a white, middle-class English woman many of my assumptions and linguistic expressions are specific to my particular culture and background.

The three clients, Julia, Mary and Louise, are actually fictional characters made up from a number of different clients, students and friends. Any potentially revealing details have been changed, for the sake of confidentiality.

WHAT IS FEMINIST COUNSELLING?

Feminist counselling is not just a technique or style. There is no school of feminist counselling. For me it is about a different way of being, having different attitudes to each other and different values and ways of thinking. Feminist counselling is not only about living more fully in the present, like most other forms of counselling. It is also about working towards the future. It is training people, men as well as women, for a society that does not yet exist; a society in which so-called ‘feminine’ values and ways of thinking are valued as much as so-called ‘masculine’ ones.

‘Feminine’ and ‘masculine’ are words that are burdened by so many layers of socially constructed meaning that I would prefer not to use them at all, so when I do they have inverted commas round them to remind us of their limitations. Yet the words ‘female’ and ‘male’ imply some kind of rigid biological determinism that I also reject. This book does, however, stress real differences in ways of thinking that thousands of years of patriarchy have associated with females and males respectively. It does not mean that male people are genetically incapable of using ways of thinking previously associated mainly with female people, or vice versa.

Broadly speaking, the way of thinking associated with males separates out elements of a situation into distinct categories. It then tends to focus on one element as opposed to the other. It may involve a competition between them in which one must eventually win. In everyday terms it could be seen as prioritizing, as between home and work. One element is chosen and the other rejected. This way of thinking is a necessary part of life, but if taken to extremes, it means that everything gets permanently divided into superior and inferior, for example, work is always seen as superior to home. It becomes rigidly hierarchical, as are most patriarchal societies.

On the other hand, the way of thinking associated with females, that I call the rhythm model, stresses the interrelatedness of opposites in a situation and can allow movement from one to the other at different times. If taken to extremes it can involve a one-sided rejection of difference and separateness. But more usefully it can be seen as an equalizing process between different elements. Yet because the ‘female’ model allows for its own opposite, the ‘male’ model, it can itself contain both of them, in their non-extreme forms.

There are also values which have become associated with females and males respectively. For instance, competitiveness and goal seeking have become associated with males and caring for others with females. Both these values are important and necessary, for women and for men, but in a patriarchal society the values associated with females are viewed as permanently inferior. Feminist counselling is helping to prepare people for a society in which nurturing and co-operation are respected as much as independence and assertiveness.

Feminist counselling rejects the prevailing hierarchical model of thinking in which one ‘side’ must always win. It recognizes the interconnection between different, even opposite, sides of life and of ourselves. This is a totally different approach from the one on which most of our modern thinking is based, in which we are taught to strive all the time for set goals and to move in one direction up a hierarchical ladder. The feminist counselling model is more like a spiral path that goes backwards as well as forwards through many cycles of development and fulfilment. We can move between our conscious and our unconscious, our joy and our sorrow, our activity and our rest, our ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ worlds.

The rhythm model as a form of equalizing and balancing is central to ecology and alternative holistic medicine, to new age spirituality and humanistic psychology. It is also related to other ‘progressive’ movements in the world that are struggling towards greater justice and equality. It is about respecting and celebrating differences such as female/male, black/white, as opposed to the present view of difference that is concerned with superiority and inferiority, winning or losing, or flat denial of difference altogether. Feminist counselling is profoundly social and political as well as personal and individual.

In common with the radical therapies of the 1970s (Steiner and Wycoff, 1975), an essential feature of feminist counselling is our recognition of the deep interconnectedness of our ‘internal’ psychological worlds with the ‘external’ social and material worlds. At present, our psyches as well as our bodies are affected by life in a competitive hierarchical society. In particular we are aware of the impact of ‘second-class’ status and gender stereotyping on women’s psyches and on the way we think about ourselves and others. But we also recognize the damage that masculine stereotyping has done to male psychologies.

Feminist counselling is also concerned with the profound influence of other social hierarchies such as race and class, sexual orientation and disability. In addition to economic disadvantage, certain groups of people are made to feel inadequate and inferior in many different ways. In place of hierarchical thinking, we help people to value all sides of themselves. Different characteristics can be used at different times. We can alternate through time, for example being strong one day and vulnerable the next. In the same way, we believe that society could use and value differences between groups, rather than defining one group as permanently superior to and in charge of the other. No one part of ourselves, such as our ‘head’, need always be in control of another part, such as our ‘heart’. Many people come into counselling terrified of letting go the rigid control that they consider their ‘heads’ must have over their ‘bodies and emotions’.

The ‘Feminine’ Rhythm Model versus the ‘Masculine’ Control Model

Throughout this book the concepts of rhythm and the interconnection of opposites will come up. I work with a model of life (the ‘rhythm model’) which helps to make sense of the world and our own selves, and is fundamentally different to the model which is generally unthinkingly accepted in society, which I call the ‘control model’. A model is essentially a simplified image of the way we perceive the world, a kind of half-way stage between ‘inner’ imagination and ‘outer’ reality. The ‘rhythm’ and ‘control’ models are two contrasting ways of seeing relationships between people and things. They are also the underlying supporting structures for two very different kinds of ideology, one pro-equality and the other pro-hierarchy.

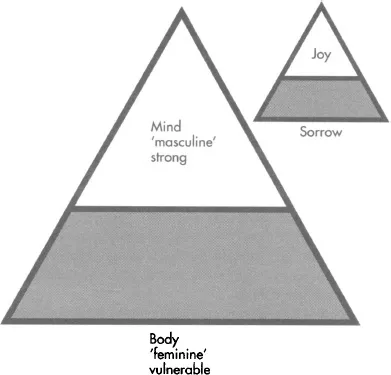

FIGURE 1 The control model

Unconsciously we use the control, hierarchical model most of the time, at least in Western cultures. But we rarely visualize it as a concrete image. Figure 1 shows the control model in a simple two-dimensional form. The opposites are split hierarchically, and the model is shown as a pyramid. The shape is arrow-like, yet static. It suggests a climb upwards towards the peak, the success, the goal or even God. But the upward-thrusting movement is frozen in its tracks. It is fossilized. The pyramid is a powerful image of hierarchy, with the minority at the top ruling the majority at the bottom.

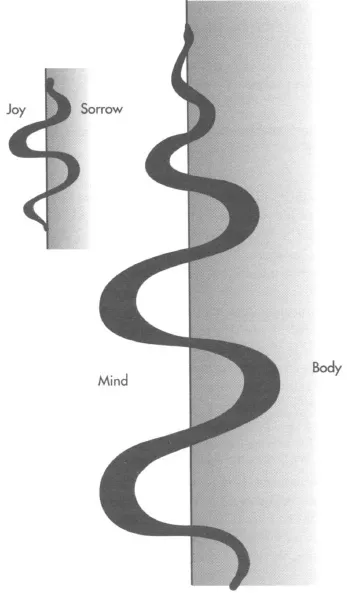

Figure 2 shows the rhythm model, which has a far greater sense of movement, change and life itself. The movement is from one opposite side to another. It can be seen as motion through time, as a dance or even a struggle arising from the tensions between the opposites. When one movement has reached an extreme, there is a swing back to another one. It is a kind of balancing mechanism that we know goes on throughout nature. Yet perfect, permanent balance is never achieved, for that would be the end of the dance, or death. The path of the rhythm could be seen as the path taken by a person who experienced first joy and then sorrow, first strength, then vulnerability at different times of one day or one lifetime. And then at some stage they return to the first state, and so on. It is a model describing the alternation process that connects the opposites through time. It has been described as the ‘feminine mode’ (Perera, 1981): ‘Alternation, the oscillating way, is a function of the feminine self.’

FIGURE 2 The rhythm model

How Does the Non-hierarchical Rhythmic Model Affect our Practice?

Feminist counsellors are committed to transforming hierarchical relationships into more egalitarian ones, whether these be in society at large or in the consulting room. But what about the counsellor-client relationship? Isn’t that inevitably hierarchical? No. Too often equality gets confused with sameness. The client and the counsellor are not the same; they have separate and different roles. But the counsellor is not there to dominate or have power over the client. Women and others at the bottom of hierarchies usually have enough experience in their everyday lives of being dominated or put down, and the low self-esteem resulting from such experience is often what brings them to counselling in the first place. Feminist counselling aims instead to empower people and help them develop more self-confidence and control over their own lives. The counsellor is not seen as the expert or the doctor; the client is not a patient. Rather they are two different people using ‘clues’ to explore the life of one of them. The focus is on the client. The counsellor is not there to explore her own life. Her role is one of container, supporter and enabler. ‘Containing’ here means being present with the client in a firm but accepting way and not being afraid of strong feelings. The client’s role is one of self-exploration. Neither counsellor nor client is superior.

It is however important to remember that when some clients first come into counselling, they are coming in with the old hierarchical ways of thinking deeply ingrained. They expect to be told what to do. They are looking for Mummy and Daddy. As feminist counsellors we try to respect clients’ present reality as we help them to develop alternative ‘ways of seeing’. We may accept the parent role initially until the client learns to do without it.

Dealing with Objective’ and ‘Subjective’ Realities

We also respect and acknowledge the ‘objective’ realities of the client’s life as well as the ‘subjective’ inner world of her thoughts and feelings. Subjective and objective are seen as two more interconnected opposites, though of course we recognize the problems involved in separating the two. For example, a woman client who was unable to work effectively in the office because of her rage against a male boss would have her objective situation taken seriously. Events are often ‘seen’ from a male viewpoint, so that the experience of women is made to seem less ‘real’, less ‘valid’. Feminist counselling should never belittle a client’s view of her experience. The angry woman would, however, be encouraged to divide the situation into ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ aspects. On the objective side would be the detailed realities of what the boss actually says and does that offends her. It would include the structure of the office hierarchy and the roles men and women are expected to play. The subjective side would involve expressing her own feelings and thoughts about the situation and making connections with other similar situations, possibly in her childhood.

For example, the behaviour she cannot stand might include being touched invasively while talking about business. This touching is objective harassment. But on the subjective side she may be letting it happen because she is too scared to say ‘no’ to it. To deal with objective realities she might be encouraged to take action through her union if there is one, but she would also be encouraged to act more assertively towards the boss. She might have to practise new more assertive behaviour with the counsellor many times before she feels comfortable acting it out in the office.

On the subjective side, she might be finding it especially difficult to be assertive with her boss because her father used to behave in a similar way when she was a child. And some (but not all) of her present rage comes from the past and from unexpressed anger towards her father. Feminist counsellors can work on both levels. We are concerned with ‘external’ behaviour change as well as ‘internal’ changes to feelings and thoughts. Ex...