Introduction

The new media - from email to blogs to YouTube to Twitter - have driven major changes in who we communicate with, from where, and when. Similarly, they are driving changes in what we can and want to do in the online and on-campus classroom, and when searching and learning via the web. The differences and affordances of each of these modes of communication underpin the revolution in e-learning. Thus, it is well worth reviewing some of the fundamental differences between communicating via computer media and communicating face-to-face. This serves as a starting point for understanding what makes e-learning different from face-to-face learning.

We use computer media so frequently and in such an integrated manner with daily life that it is no longer practical to talk about computer-mediated communication (CMC) versus face-to-face communication. Yet, there are major differences between face-to-face and online communication, such as the text interface and asynchronous communication. Awareness and attention to these differences helps in understanding how these technologies can best be used, or adjusted for use, for e-learning. Also important is unbundling the medium from the desired outcome. For example, often people feel that in a move from face-to-face to CMC, they lose the richness of the intimate circle of others. But if we unbundle the intimate circle from the medium, we may find that what is lost is the immediacy of interaction and the close attention of others. The desired outcome of ‘immediacy’ and ‘attention’ can then be addressed with social or technical enhancements, for example more rapid feedback in asynchronous discussions or a synchronous connection with a critical mass of remote learners. In looking at CMC ‘versus’ face-to-face communication, there may be some losses, but there are also gains. Many studies and many successful online programs and collaborations indicate that learning and working together online and through computer media can be a satisfying and productive experience. Our task is to find out how best to make that happen.

We feel the aim is not to judge whether online is better than offline, but rather to work from the idea that if you cannot meet face-to-face, how are you going to make the best effort to create and sustain a productive learning environment? What do we need to know – about learning, media and social interaction – that can help inform our participation in learning environments whether as a novice, expert, student or teacher? This approach applies equally to the now common blended or hybrid learning environment that combines face-to-face meetings with deliberately designed online activity. What do we need to know to appropriately distribute learning experiences across these offline and online settings? The first answer to these questions is that we need to understand the basic differences between offline and online communication on our way to making deliberate use of these features for learning.

Features of Computer-Mediated Communication

The earliest observers of CMC noted that computer media convey far fewer communication cues between speaker and audience than face-to-face communication (e.g. Kiesler, 1997; Kiesler and Sproull, 1987; Sproull and Kiesler, 1986; Walther, 1996). Email lists, for example, permit communication via text from an unseen speaker to an unseen audience of indeterminate size and composition. Email – and many forms of CMC that follow – hide visible signs of gender, race and age, prevent us from picking up cues associated with how people dress, and remove from the communication a range of nuances normally added through voice, hand gesture and body language. Unless explicitly stated in messages, the status and provenance of the speaker are also invisible. At first this all seems a terrible loss, particularly if you are the person losing status by the inability to be seen. But, this status flattening has had positive effects for those who are shy about responding, or were previously prevented or inhibited from contributing because of low work status.

A key aspect – even a benefit – of CMC is the way it allows unbundling of the message from cues which are tightly bound with face-to-face communication, in particular cues about individual identity and setting. Along with unbundling, CMC can also be combined and used in ways that allow a rebundling that suits the new setting (Haythornthwaite and Nielsen, 2006). This is a particularly salient point for addressing issues of shyness, turn-taking, or remote participation in e-learning settings. While it is possible to try to re-introduce all the cues of a face-to-face setting, for example through multiple video feeds from different sites, a rush to recreate the many cues can lose the benefits that a lean, text-based, asynchronous setting confers. Such benefits include the ability to post simultaneously, to post after reflection, and to form thoughts into text, a prime communication mode in learning and education.

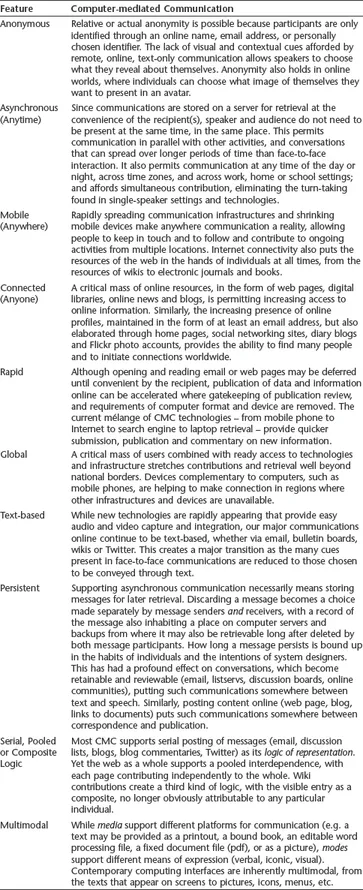

Both face-to-face and CMC afford different possibilities for communication, but both have their merits for communication outcomes. Face-to-face communication in small groups permits a richness of communications cues that provide multiple types of information about others; lean CMC permits selective presentation of cues, providing control over what kinds of information are conveyed to others. Anonymity – or the relative anonymity possible when so many cues about an individual are missing – is one of a number of affordances of CMC. Box 1.1 provides background on the idea of affordances. Other major affordances of CMC are listed in Table 1.1, highlighting those that differ from the affordances of face-to-face communication. These include anonymity, but also the way CMC affords asynchronous (anytime), mobile (anywhere) communication that potentially connects widely to other people (anyone), both locally and globally. New forms of data capture, such as digital cameras, and of communication, such as blogs and blog comments, afford rapid updating and aggregation of information.

Affordances of CMC technologies – whether email, bulletin boards, wikis, chat or video – create opportunities for conversation, learning and the creation of common understanding and purpose, just as face-to-face conversation can and does. Yet, the conditions are different. Awareness of differences and possibilities helps in planning their adoption and use, as well as in recognizing where changes are happening outside the traditional learning setting that will affect supposedly ‘closed-room’ learning (e.g. as laptops enter the classroom). The following sections discuss some of the ways that features listed in Table 1.1 can be considered for their effect on interaction in learning contexts.

Box 1.1: Affordances

The idea of affordances stems from the work of Gibson (1979) referring to what an environment affords an animal in that context. This idea was adapted for discussion of design of material artifacts by Norman (1988), and for computing technology by Gaver (1991, 1996). It has also been extended to design that considers patterns of social interaction in the idea of social affordances proposed by Bradner, Kellogg and Erickson (1999; see also Wellman, et al., 2003). Each of these writers addresses the latent potential of the object of interest (environment, artifact, interface) for the actor approaching the object. While there is some distinction among them on how much an actor needs to be aware of the potential dangers and/or use, considering what an object allows or makes possible is useful for many areas of endeavor. Thus, we can think about the way social networking affords interaction among distributed participants, but also affords transmission of computer viruses and loss of privacy. The idea of affordances is particularly useful as a way to approach design and is well used in this area for computer systems design (for a critique of the use of the concept with reference to technology and learning, see Oliver, 2005a). In some cases this is taken at the very close level of what a computer screen feature allows: radio buttons afford clicking; windows allow separation of application uses; scroll bars afford navigation within a window. Attending to affordances can also be used to focus on the capabilities of a system rather than the particular instantiation of its use: the way a system allows remote connection, asynchronous communication, data collection, navigation, awareness of others, etc. While systems may afford certain features, it is often not until a combination of social and technical features align that a particular affordance reaches its potential. Chapter 7 goes into more depth on this sociotechnical perspective.

Anonymity

Anonymity can be highly important for gaining contributions from people who are not comfortable with participating, whether from shyness, lack of familiarity with ways of contributing, second language use, or concerns about how they will be judged for their submission. Thus, anonymity may be a good way to begin online contribution among new e-learners. However, longer term, it becomes important to trust what is happening to freely submitted ideas and information, and thus to get to know others in the learning group. Face-to-face, physical cues such as gaze and body language help confirm the spoken message, helping to build trust between people. Since these are lacking when only CMC is used, other means of building trust need to be established. Identifying others is a first step, and that can be done by knowing who is talking (see Case 1.1). This provides continuity in identity over time as conversations continue and allow participants to build a mental model of the people with whom they are interacting. Even if not using a real name, continuity in identity at least creates a known history within the group and helps participants know who is talking. Sharing a history provides a common ground that can reduce the amount of joint work needed to facilitate discussion (Clark and Brennan, 1991). Over time, individuals gain reputations as experts, information providers, information gatekeepers, and synthesizers of knowledge (Montague, 2006; Preston, 2008; see also Haythornthwaite, 2006a, 2006b). When we recognize that certain group members hold specific skills or knowledge it becomes easier to know what to do with information or information requests and for the group as a whole to operate effectively (Haythornthwaite, 2006a; Wegner, 1987; for more on this, see Chapter 9).

Case 1.1: Please Post Your Story!

Christie Koontz, Florida State University, USA

Each semester I ask the students in my online classes to write a mini-biography and post it along with a photo during the first week. The bio includes their name and professional background, where they are physically located (and hence where they are coming in from for the distance class), favorite web links expressing personal and professional interests, and career goals. Then, in that first week, I write each one an email in response and welcome them to the class, mentioning something they shared with me, so they know my response is not canned. In the next class, I allow time for students to peruse these bios and post a response to at least one. This activity introduces students to each other, some of whom may be in the same town. Privacy issues do not allow us to post who is where, so this activity provides a mechanism to facilitate a personal touch in several directions. My online mentor, a fellow faculty member at Florida State, introduced this activity to me. I share it with new faculty who observe my classes as a really successful online technique. I teach marketing, storytelling, management, foundations and supervise internships and it works well for all these classes.

Christie Koontz is a faculty member in the School of Library and Information Studies, Florida State University, USA.

Asynchronous, Mobile and Connected

Asynchronicity sets the stage for anywhere, anytime, and anyone communication. It removes the necessity for all participants to be in the same physical or online meeting place at the same time. Thus, it is an ideal solution for distributed, on-the-go learners. It fits well with our contemporary, cluttered schedules which are filled with work, family and social obligations. It also serves ubiquitous learning well since it can be managed on a just-in-time and as-time-is-available schedule: formal learners can choose when to dip into and join online class discussions; lifelong learners can pick up new information and skills as and when needed; and everyday learners can search the web now for information on today's activity.

In discussing media affordances, we should note in the context of e-learning that asynchronicity and distributed participation – in time or location – are not just the purview of structured classes, nor only of online classes. Those who attend traditional classes may manage out of class tasks asynchronously through computer media, for example in the management of group projects. Similarly, online classes may meet synchronously, through chat, audioconference or videoconference. What is of interest is the way the uses of these technologies, individually or collectively, create opportunities for communication and interaction.

Box 1.2: Describing Learners

Basic distinctions between formal and informal learning already exist in the literature. The formal learner follows their study in the context of degree or certificate-granting institutions (e.g. schools, colleges and universities). Once ‘formal’ describes the space, ‘informal learning’ becomes what's left. It is marked by a lack of the specific teacher–student relationship, but may retain a hierarchical aspect: parent–child, supervisor–employee, master– apprentice, expert–novice, guru–newbie. It can entail learning of a serendipitous nature that happens without an agenda; it can mean self-directed learning to personal goals, hence with an agenda but not one set by a teaching authority; and it often refers to acquiring process (how-to) knowledge rather than content (know-what) knowledge. Thus, the informal learner is found engaged in many kinds of activities. (For more on informal learning and education, see the online resource, The encyclopedia of Informal education at http://www.infed.org/). Building on definitions from the UK Department for Education (DfE), Garnett and Ecclesfield (2009) make a distinction between formal, informal, and non-formal learning, with the latter as structured learning without formal learning outcomes. These authors model the relationships between these types of learning to pursue the idea of learner-generated contexts (Luckin, 2010; Luckin et al...