![]()

1

Introduction

An introductory exercise

Suppose that you wanted to understand the changing meanings of the greeting cards in twenty-first-century London. You are particularly concerned with these meanings and uses among young single adults aged 18–30 who are more likely to be online, socially active, and looking for work or embarking on careers and advanced education. You know that e-cards are increasingly popular, but wonder whether both e-cards and traditional paper cards are likely to be seen as old fashioned by this target group. You also know that Greater London is culturally diverse and composed of many ethnicities and subcultures. And you know that the answer to your question is likely to differ over various card-giving occasions and non-occasions as well as over different types of relationships. How might you go about answering your question? See if you can think of at least one study using each of the following methods:

- survey research administered online;

- focus group discussions;

- observational research;

- individual depth interviews;

- a study of online material in forums, discussion groups, and social media;

- archives of the records of a subscription service offering online greeting cards and gifts.

Try to detail how you would go about conducting the study and what you would observe, ask, or analyse. If you could only use one of these methods, which would you choose? If you could use three of these methods, which three would you use and in what order would you use them? Jot down some notes about how you would conduct and use each of these types of studies, then put your notes in a safe place. After you have completed reading this book or a substantial portion of it, return to these notes and see how you might respond to the exercise at that point. We anticipate that you may well formulate the research differently after reading the chapters that follow and participating in other exercises along the way.

This book has one relatively straightforward goal. We want to help you develop skills in doing qualitative research. Our aim is to provide practical advice that will be valuable to you, whether you are a budding scholar, a budding practitioner, or someone who has been dabbling with qualitative methods (whether in academe or industry) and who wants to get better at using them.

This book also has some slightly more ambitious goals. We want to help promote a wider understanding of the differences, as well as the commonalities, in the ways qualitative research is conducted depending on the purposes for which you are using it (such as to develop a communications strategy for a new product versus to write a journal article for publication). For those doing qualitative corporate research addressing applied business problems, we want to highlight guidelines for what makes effective research. For those who are doing qualitative research and hoping to publish it in academic journals or books, we want to provide some guidance on different traditions that have evolved among scholars studying consumers, markets, and marketing. Depending on which tradition(s) a scholar or corporate researcher works in, they might well collect different types of data and do different kinds of analyses to build theory. The nature of theory itself also differs across contexts. So if this book is to achieve its straightforward goal of helping you do better qualitative research, it needs to pursue these distinctions in the purposes of the research you wish to do.

What makes qualitative research different from quantitative research?

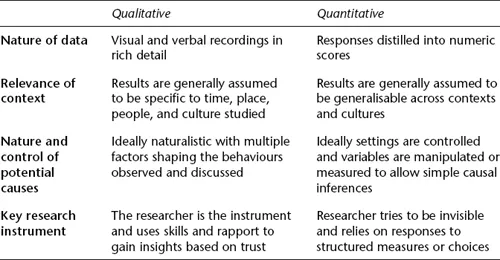

To take the first step toward achieving all our goals, we begin by telling you what we mean by qualitative, versus quantitative, research. First, we point out something they have in common. We believe that all research is interpretive, whether that involves interpreting patterns in relationships between quantified observations or in recurring patterns in talk, text, images, or action. Thus we do not consider being interpretive something that distinguishes qualitative from quantitative research. So what is different? Table 1.1 summarises the basic differences that we will discuss here. Other, more nuanced differences will become clear in the chapters that follow and are also discussed by Sherry and Kozinets (2001).

Table 1.1 Qualitative versus quantitative research differences

Richly detailed data, not quantified data. One rather obvious but salient characteristic of qualitative research that is distinctive is that it entails, primarily, the analysis of data that has not been quantified. This is not to say that qualitative researchers never provide numbers to support some aspect of their analysis; it is perfectly acceptable to include numbers in a supporting role. However, the core contribution of a piece of qualitative research lies not in reducing concepts to scaled or to binary variables that can be compared and contrasted statistically based on the assumption that they provide meaningful measures of the behaviour they seek to understand. Instead, it builds upon detailed and nuanced observation and interpretation of phenomena of interest. Doing so requires a commitment to illustrating concepts richly, whether with words or images or both.

Contextualised rather than decontextualised. A second, related, characteristic distinguishing qualitative research is that it is contextualised: it takes into account the cultural, social, institutional, temporal, and personal or interpersonal characteristics of the context in which the data is collected. While quantitative research may sometimes be contextualised, it is often the case that quantitative data from distinct contexts are gathered and combined, and that interpretations stress that which is assumed to be generalisable across times and places. In qualitative research, data are frequently gathered from a single context or a narrow range of contexts, and immense care is taken to understand how the context matters to the phenomena under consideration. Theoretical claims and managerial insights developed from qualitative data analysis are thus based on characteristics of the context, and it is common for qualitative researchers to circumscribe the domain within which their findings are applicable as a result of the context of the research. For example, a doctoral student in our department, Mandy Earley, is currently doing research on the activists in the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York City. Both the time and place in which this observational and interview data are being gathered constrain attempts to generalise to Occupy movements in other times and places.

Naturalism versus control. A third characteristic is that when qualitative research entails interviews or observations, these are often conducted in settings where people live, work, play, shop or just hang out rather than in settings that are controlled by the researcher, such as laboratories. While exceptions do exist, it is normal for qualitative researchers to try to observe and interact with people in the contexts that shape their everyday behaviours and perceptions. This ‘in situ’ characteristic of qualitative research contributes to its ability to capture insights that cannot easily be communicated by people who take for granted what is going on in the settings they frequent. And it means that qualitative researchers can often learn things that the people they study may not be able to articulate. For example, one of us (Eileen) is currently observing entrepreneurs’ use of Twitter to communicate with stakeholders. She interviewed them first to see what they explicitly state about why and how they communicate. Her analysis thus far shows recurrent patterns in the tweets of some entrepreneurs, such as the use of intensely emotional language. These emotion-laden tweets would not have been anticipated based on interviews alone, and variation in emotional language usage would not likely have been considered for inclusion in a controlled experiment on social media based corporate communication. In this project as in many others, the naturalism of observing actual behaviours affords insights that would otherwise have been missed.

Researcher as instrument versus detached instrumentation. A final point of differentiation between quantitative and qualitative work concerns the researcher’s relationship to the data. With quantitative research, care is taken to create instruments (such as questionnaires) that are meant to reduce the impact of the researchers on the data that is collected. In qualitative research, the researcher is the primary instrument of data collection. The researcher’s skills in building trust as well as in hearing and seeing what is going on in a setting, and in asking questions that could not have been anticipated prior to immersion in the setting, are crucial to the success of a qualitative project. Rather than the hands-off and distant approach of most quantitative research, the qualitative researcher develops a deep connection to the context being investigated and often builds a relationship with those being studied.

Why is qualitative research so valuable?

All three of us have immense respect for the insights that quantitative research can yield. But as people who have spent most of their professional lives using qualitative methods to understand the things that interest us, we are convinced that qualitative research is invaluable because it provides unique insights into how consumers, marketers, and markets behave, and into why they behave as they do.

Take Christmas gift shopping as an example. In particular, let us try to understand how the Christmas shopping gets done, and why the work of gift shopping tends to get divided rather unevenly in so many families, with women doing the bulk of the work in households that include heterosexual couples (Fischer and Arnold 1990). Quantitative approaches are excellent for measuring variables such as how many gifts each member of a household purchases, how many hours the adults spend shopping, how much money they spend per gift, and how many ‘self-gifts’ each person buys as they shop for other people. They are also great for looking at patterns of association between social psychological variables (such a gender-role attitudes or gender identity) and specific shopping behaviours.

But qualitative research can help to identify the cultural discourses and market place mythologies that infuse shopping activity with meaning. They can help us understand that Christmas gift shopping has, in North America, been socially constructed as an extension of the feminised work of caring for and perpetuating the ties that matter to families. They can help us, too, to understand the varied experiences recounted by people who enjoy the ‘fun’ of Christmas shopping in the intensified retail environment that builds to a peak in the weeks leading up to 25 December, compared with those who dread the harried overload of work that Christmas shopping entails, and who attempt to incorporate gift search into their routines throughout the year (Fischer and Arnold 1990). They can also help us understand what consumers mean when they refer to a gift recipient who is ‘difficult to buy for’ – and to appreciate that consumers feel someone is easy to buy for when they can fulfil certain desirable social roles by shopping for them (Otnes et al. 1993).

As this example illustrates, quantitative approaches are neither inferior nor superior to qualitative ones. Whether you are a marketer trying to help stressed-out women ‘cope’ with Christmas or a scholar attempting to understand the persistence of patterns of gendered division of labour, when it comes to complex everyday phenomena, quantitative and qualitative methods can be invaluable complements.

Why is it important to learn to do qualitative research now?

We believe that there has never been a time when it has been more important for qualitative marketing researchers, whether they are practitioners or scholars, to develop and refine their skills in doing qualitative research. Why do we make this assertion? There are several reasons.

First, the contexts where qualitative methods can be fruitfully applied are evolving rapidly. In particular, the burgeoning range of online activities in which consumers and marketers are engaging – whether they are networking via social media sites, making exchanges in online markets, or sorting out complaints via company websites – means that there are abundant new contexts where qualitative data can be collected and where new insights into consumption and marketing can be generated. A related factor that is leading to an explosion of new research contexts is the growing appreciation of the need for investigations of contexts outside more economically developed, formerly ‘first world’, countries. And qualitative methods are well suited to investigating consumer and marketing phenomena within cultural contexts that have previously been overlooked, or across cultural contexts that vary dramatically from one another.

Second, among marketing managers, there is a growing appreciation for the insights that skilled qualitative researchers can bring to bear. The types of qualitative research that managers are commissioning extend well beyond the traditional focus group, encompassing ethnographic interviews, netnographies, pantry studies, shop-alongs, and much more, as we discuss in Chapters 4, 5, and 8. At the same time, the standards by which managers are judging the quality of the research they commission continue to be demanding. Those who provide qualitative research services are required to be able to tailor their approaches and integrate new techniques for data collection on a continual basis. And, regardless of their techniques or data sources, they need to be able to provide inspiring interpretations that facilitate managerial decision-making. In fact, growing competition in most industries and the continual ‘scientising’ of professional managerial functions in global businesses have led to increased demand for data analysis that cuts across every type and form of data. Business has a bottomless appetite for quality data to inform its decisions. It is these developments, along with a growing sense of the need to get a deeper understanding than numbers alone can provide, that seem to account for the rise of qualitative marketing research methods at a time when scanner panel data, online analytics, and other quantitative measures of consumption and competition are more readily available and abundant than ever before.

Third, for scholars working in the fields of consumer behaviour and marketing, there are many more publication outlets that accept qualitative manuscripts for consideration and that publish a number of qualitative papers each year. Although a small (and decreasing) number of journals cling stubbornly to biases against all qualitative research, the good news is that the majority of so-called top tier publications are now open to publishing qualitative research if reviewers can be satisfied that a manuscript features qualitative data that are rich and relevant, incorporates data analysis that is systematic and thorough, and offers theoretical contributions that are insightful, original and important. The same is true for outlets for videographic consumer and marketing research, as discussed in Chapter 9. Consumer research film festivals, special DVDs and online issues of journals, refereed online video streaming websites, and various broadcast and narrowcast outlets all have a hunger for good quality videographic work.

One challenge – and this is also an opportunity – for scholarly qualitative researchers lies in understanding what any given set of peer reviewers will regard as an insightful form of theoretical contribution. Although there may be considerable consistency in judgments of whether data are rich and relevant, and some consensus on how an analysis can be credibly constructed, there is considerable disparity between communities of qualitative researchers as to what constitutes an insightful theoretical contribution. We will elaborate on this point in Chapters 7 and 8, but here we want to make the point that, if you are going to publish qualitative research, you will be ahead of the game if you start from the premise that there is no one gold standard when it comes to how you should craft a theoretical contribution. Rather, there are diverse sets of practices that you can learn to identify and adapt to depending on where you want to publish. For instance, within some leading journals, the normal way of expressing theoretical contributions is by creating an inventory of propositions; in others, propositional inventories are virtually taboo and findings are expressed in terms of interrelated themes. We believe that the diversity across communities of qualitative scholars is too often glossed over, and that a practical guide such as ours will benefit readers most if we not only tell you about the techniques you may use to gather qualitative data and the approaches you may take to analysing it, but also about the different trajectories of qualitative research practice that have evolved when it comes to crafting contributions.

Qualitative researchers who have a foot in both industry and academe also need to appreciate that the conventions for conveying contributions in these two fields of practice vary considerably. All three authors of this book currently are or have recently been associate editors at top journals in the field. All of us have a wealth of experience as authors and reviewers. In addition, we have also been involved in industry enough to be able to offer perspectives from a range of different and even divergent perspectives. So we are equipped to offer guidance that should help you gain traction in doing qualitative research that will be well received by your intended audiences.

Qualitative research in marketing: a brief history

To appreciate the current practice of qualitative research in marketing today, it is valuable to consider how and when qualitative approaches started to gain currency. In order to do so, we need to distinguish between the fields of academe and industry, since qualitative research of certain types were granted credibility among marketing managers long before it became possible to publish qualitative work in scholarly journals.

The evolution of qualitative market research in industry

Marketing historians identify the 1930s as the decade during which qualitative approaches to applied marketing research first gained recognition (Levy 2006; Kassarjian 1995). In particular, Paul Lazarsfeld, a native of Austria and a leading figure first in European and later in American marketing thought, produced studies through his Institute for Economic Psychology that included systematic analysis of hundreds of interviews conducted with consumers (Fullerton 19...