eBook - ePub

Urban Regeneration in the UK

Boom, Bust and Recovery

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A thorough update of what was already an excellently written, accessible and well-used book. Coverage of the key issues to impact on regeneration in the UK since the 2008 financial crisis is comprehensive, and ensures that this latest edition will remain a key reference work for students and practitioners alike.

- Dr David Jarvis, Coventry University and Deputy Director, Applied Research Centre in Sustainable Regeneration (SURGE)

"An accessible text for students that provides an excellent summary of the challenges facing the UK regeneration sector up to and including the present age of austerity."

- Dr Lee Pugalis School of Built Environment, Northumbria University

An engaging, systematic guide to the most dramatic transformation of our urban landscape since post-war reconstruction. This new edition has been fully revised to include:

- Dr David Jarvis, Coventry University and Deputy Director, Applied Research Centre in Sustainable Regeneration (SURGE)

"An accessible text for students that provides an excellent summary of the challenges facing the UK regeneration sector up to and including the present age of austerity."

- Dr Lee Pugalis School of Built Environment, Northumbria University

An engaging, systematic guide to the most dramatic transformation of our urban landscape since post-war reconstruction. This new edition has been fully revised to include:

- Improved pedagogical features, including an expanded glossary and increased visuals, as well as key learning points, useful websites and suggestions for further reading

- More content on local sustainability and issues linked to climate change

- A new chapter, ?Scaling Up?, which examines how regeneration operates when considering very large schemes, such as the London 2012 Olympics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Regeneration in the UK by Phil Jones,James Evans,SAGE Publications Ltd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

OVERVIEW

- Defining urban regeneration: explores the origins of the term and how it has come to be used within contemporary policy.

- Scale of change: gives the context for regeneration, looking at the scale of development in the UK and examining the importance of sustainability as a guiding concept.

- From boom to bust: examines how wider global and economic trends have impacted on the way regeneration is carried out and the political response to this.

- Scope and structure of this book: provides a breakdown of the different chapters within the book.

- How to use this book: outlines some of the ways this book can help to develop an understanding of urban regeneration.

Introduction

For the decade leading up to 2008, towns and cities across the UK were undergoing a series of dramatic reconfigurations, the scale of which had not been seen since the 1960s. Shiny buildings in glass and steel seemed to spring up overnight and cranes dominated the skyline of our major cities. Older buildings and sometimes whole districts were razed to the ground to be replaced by new kinds of urban development. Terms like ‘sustainable’, ‘mixed use’, ‘café culture’ and ‘waterfront redevelopment’ became commonplace. The process profoundly transformed aspects of urban life – both the way towns and cities look and how we live in them. A spirit of optimism dominated the process, with regeneration seen as an important opportunity to rectify the mistakes of the past to create attractive, sustainable places for people to live, work and play.

During his time as Chancellor, Gordon Brown spoke of the need to end the cycle of boom and bust that had plagued the British economy since the end of World War II. The credit crunch of 2008 and subsequent recession put paid to the dream that the UK had entered a period of sustainable growth. Major building projects were suddenly put on hold or cancelled altogether as finance dried up and firms started to go bust. As the economy slowly starts to recover, regeneration activity is also starting to build up again, though in a somewhat less feverish way than at the height of the boom. The credit crunch injected a healthy dose of reality into the UK’s overheated property market and gave an opportunity to think again about what regeneration is trying to achieve in terms of improving our towns and cities, rather than simply how regeneration can be used to maximise profits for private firms and individuals. In short, it is a very good time to be interested in urban regeneration. But what does ‘urban regeneration’ actually mean, how does it work and what does it do? These are the questions this book sets out to answer

Defining ‘urban regeneration’

Cities are never finished objects; land-uses change, neighbourhoods are redeveloped, the urban area itself expands and, occasionally, shrinks. Pressure to change land-uses can come about for a number of reasons, whether it be changes in the economy, environment or social need, or a combination of these. The large-scale process of adapting the existing built environment, with varying degrees of direction from the state, is today generally referred to in the UK as urban regeneration. Some of the core elements of regeneration have appeared in urban policy before, albeit with slightly different labels. In post-war Britain there was a discourse of reconstruction, not only addressing areas which had suffered the destruction of wartime bombing, but also demolishing the large areas of slum housing that had been jerry built during the nineteenth century to house a growing urban industrial workforce. This post-war reconstruction was somewhat akin to urban renewal in the United States, wherein large parts of the inner cities were demolished and replaced with major new roads, state-sponsored mass housing and new pieces of urban infrastructure.

Urban regeneration is a newer concept, which arose during the 1980s and, as a label, indicates that the process is about something more than simply demolition and rebuilding. The urban sociologist Rob Furbey has written about the origins of the term, reflecting that ‘regeneration’ in Latin means ‘rebirth’ and embodies a series of Judaeo-Christian values about being born again. This notion was particularly appealing during the 1980s, when urban policy under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher swung towards the neoliberal and was influenced by a very particular vision of Christianity, centred on the individual rather than the broader community. In a sense, therefore, regeneration – as opposed to mere ‘redevelopment’ – became akin to a moral crusade, rescuing not only the economy but also the soul of the nation. The phrase also functions as a biological metaphor, with run-down areas seen as sores or cancers requiring regeneration activity to heal the body of the city (Furbey, 1999).

One of the most significant figures in the early history of urban regeneration was Michael Heseltine who served as Secretary of State at the Department of the Environment between 1979 and 1983. This was a crucial period in the history of British cities, partly because Heseltine drove through the right-to-buy legislation which allowed tenants to buy their council houses at substantial discounts – a part-privatisation of social housing that massively increased owner occupation. Perhaps more significantly, Heseltine also led the government’s response to the 1981 riots in the deprived inner city areas of Handsworth in Birmingham and Toxteth in Liverpool. Heseltine concluded that something dramatic needed to be done and there followed a series of policy interventions attempting to redevelop derelict and under-utilised sites, bringing economic activity and social change to deprived areas.

The Conservative approach during the 1980s doubtless had its flaws, but it set a trend for large-scale interventions reconfiguring the urban fabric of areas suffering from economic decline following the shift away from a manufacturing-led economy. From relatively modest beginnings in the 1980s, regeneration has become a tool applied in almost all urban areas in the UK, reaching a peak of activity in 2008 before the property bubble burst as a consequence of the global economic collapse.

Regeneration is, however, a somewhat ambiguous term. Some approaches to regeneration argue that it is necessary to tackle physical, social and economic problems in an integrated way. In practice, however, dealing with questions around social inequality and community cohesion tend to be separated off from regeneration. Indeed, under the New Labour governments, a separate discourse of neighbourhood renewal was devised to tackle social problems (not to be confused with urban renewal as practised in the United States during the 1950s–70s). Urban regeneration, meanwhile, has come to represent strategies to change the built environment in order to stimulate economic growth. It is in this area, rather than in community policy, that this book finds its focus.

The scale of change

Urban regeneration policies helped to create and shape the pre-2008 property development boom. The growth figures for UK construction since 1997 are quite startling (ONS, 2011). Using the value of sterling in 2005, the overall value of outputs from the construction industry in England grew from £51bn in 1997 to nearly £110bn in 2008. Although this figure fell back after the credit crunch, it was still £99.5bn in 2010. The scale of growth was similar in Scotland (£5.6bn in 1997 growing to £10.9bn in 2010), somewhat slower in Wales (£2.7bn in 1997 growing to £3.9bn in 2010) and trending downwards in Northern Ireland (£3.2bn in 2001, the earliest year available for this dataset, falling to £2.4bn in 2010). These numbers represent all construction activity, not just regeneration, but demonstrate just how quickly the UK has been building. Further, this growth in construction has been concentrated in urban areas. Although in land-use terms, only around 10% of the UK’s land surface is urbanised, the percentage of total new residences built in urban areas grew from under 50% in 1985 to over 65% in 2003 (Karadimitriou, 2005).

The frenzy of building in UK towns and cities is not simply a product of economic growth, but reflects broader demographic shifts. People are living longer than ever before and, at the other end of the age scale, people are waiting longer to have children, both of which mean a decrease in average household size which, combined with a growing population means that the number of households is increasing rapidly. As a result, the number of households in England alone is predicted to rise from just over 21 million in 2004 to nearly 26.5 million in 2029 with 70% of that increase taking the form of one-person households (CLG, 2007b).

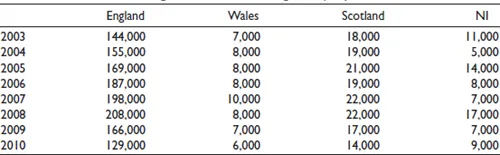

Table 1.1 shows the net annual increase in the number of homes in the UK, adding together new build and conversion of existing properties minus the rate of demolition. These data show fairly steady increases each year, with an unsurprising dip in the rate of growth after 2008. What is more interesting, however, is comparing this rate of growth as against forecasts for rates of household formation. Estimates for Scotland predict a net increase of households 2008–33 of around 19,250 per year, which is broadly in line with the rate of overall increase in housing stock (Scottish Government, 2010). Similarly, Northern Ireland is predicting an increase of around 8,100 households per year 2008–23, which is not dissimilar to its rate of stock increase (NISRA, 2010). More seriously, however, Wales is predicting household growth of 12,300 per year, 2006–31, well below the rate of stock increase (Statistics for Wales, 2010). In England the situation is even more acute, with a predicted 232,000 additional households per year 2008–33, far outstripping the number of new dwellings being added each year even at the most frenzied point of the economic boom (CLG, 2010).

Table 1.1 Number of dwellings added to total housing stock per year.

Source: DCLG Live tables on dwelling stock (http://www.communities.gov.uk/housing/housingresearch/housingstatistics/

housingstatisticsby/stockincludingvacants/livetables/, accessed 22 September 2011).

housingstatisticsby/stockincludingvacants/livetables/, accessed 22 September 2011).

The overall shortage of dwellings in England is one of many complex issues that drove high rates of house price inflation up to 2008. There was a range of other factors at work, including rising professional salaries, historically low rates of interest, the increased willingness of banks to lend more money to people with much less equity and, quite simply, a belief that house prices would keep rising which encouraged people to pay higher and higher sums for property. Nonetheless, the underlying structural shortage of housing became a real source of concern under the Labour governments 1997–2010. The Treasury in particular was concerned that housing shortage was acting as a brake on economic growth, particularly in the overcrowded south east. A series of policies were pursued to help increase the level of house-building, including reforms to the planning system. A target to increase house-building in England to 200,000 new properties per year (HM Treasury, 2005) was, only briefly, met at the peak of the boom. The broadly neoliberal politics of the UK puts an emphasis on the private sector to deliver on housing targets with a belief that reducing state regulation will allow the housing market to find a ‘natural’ balance of supply and demand. Unfortunately, relying on the private sector does not work well at a time when the housing market is sluggish and banks are less willing to lend. There is also little incentive for house-building firms to greatly increase activity if the intention is to reduce the price of their end product. Generations of politicians in England have failed to square this circle; periodic economic downturns cool house price inflation, but do nothing for the underlying structural problems in the English housing market.

A great deal of the growth in the overall number of households is being driven by increasing numbers of people living alone. In England the prediction is that by 2033, 19% of the population will live alone, compared to 14% in 2008 (CLG, 2010). In Scotland this demographic transition is even more dramatic with single-adult households predicted to increase from an already high 38% in 2008 to 45% by 2033 (Scottish Government, 2010). This has huge significance for the kinds of homes that are required. This is less of a problem in Scotland, which has a much greater tradition of people choosing to live in apartments. In England, however, the idea of the house is deeply embedded in the culture. While there has been a boom of apartment building since the late 1990s, the English do not seem to have fully embraced this housing form.

The boom in apartment construction, however, wrought a tremendous transformation upon English cities. High-density living in the heart of the city came back into fashion for the English middle classes who had largely abandoned the city core after the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike the Scots, apartment dwelling for the contemporary English middle class is very much a ‘young’ stage in the lifecourse. In the Netherlands, new inner city developments are built as large, airy apartments designed for families, with new schools to serve the incoming population. In England, new-build apartments tend to be well appointed but quite small, with a predominance of one and two bedroom units not designed with families in mind. At the same time, local authorities have not responded to the trend for inner city living by building new schools for incoming populations. Existing schools within the English inner cities tend to be of poorer quality and middle-class parents generally use their higher incomes to move to areas with good schools. Thus more than a decade of redevelopment in the core of English cities has left them with transitory populations of younger professionals, who stay for a few years to enjoy the bright lights and amenities of the city centre, before moving out to raise children in the suburbs. English city centres now have a population, but little in the way of community.

Of course there is more to urban regeneration than the rebuilding of city cores – a point that is directly addressed in Chapter 7 which considers regeneration in the suburbs. Nonetheless, it is the city centres that have grabbed the headlines and the imagination. Cities have gone to considerable efforts to re-image their central areas to make them more attractive to visitors and help to build the city as a brand in an attempt to generate inward investment. Stepping out of the train station in Sheffield in the mid-1990s visitors were greeted by a rather grim view of bus stops, a busy road and no obvious way into the city centre. Today there is a plaza paved in natural stone, an iconic curving fountain and a highly legible pedestrian routeway leading into the heart of the city. Similar transformations have taken place across the UK, with cities competing to produce iconic buildings (Selfridges in Birmingham, the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff, the Shard on the South Bank in London), create new public spaces and put on spectacular events.

These physical transformations of the urban fabric are seen as a critical part of the symbolic transformation of a city’s fortunes into the kind of place where people want to come to live, play and do business. Cities increasingly see themselves as competing in a global marketplace making branding – writ large in steel and glass – a crucial part of their strategies for economic development. This does, of course, open cities up to the criticism of putting style before substance, or even form before function. One architectural critic reviewing Colchester’s new Firstsite gallery, for example, commented that despite being a stunning building, the dramatic curved walls were not particularly well set up for the hanging of art (Moore, 2011).

The where of regeneration is fairly straightforward to understand: concentrating on previously developed (‘brownfield’) land in urban areas in order to generate growth. In turn, understanding the broader political and economic context allows us to understand the why of regeneration: in a global economy where cities are competing to attract inward investment, making those cities an attractive place to live is paramount. Perhaps the more important question that this book seeks to answer is how that regeneration takes place. A key part of the answer to this question is the rise of sustainability as a core concept. Arguably, putting sustainability at the heart of urban policy is the most important change in the transition from urban redevelopment into something we now describe as urban regeneration. Developing from an obscure concept in the late 1980s, the principles of sustainable development and the need to balance economic, social and environmental factors cut across not only urban regeneration, but UK government policy in a whole range of areas. While the concept of sustainability is notoriously difficult to pin down, it implies a commitment to protecting the environment and ensuring equal access to social and environmental services as well as economic development (see Chapter 5). The idea of ‘quality of life’ has become common parlance, as the political agenda has subtly shifted toward creating environments in which people want to be. Urban regeneration therefore not only acts as a vehicle for reinventing the economies and tarnished reputations of declining industrial cities, but simultaneously helps deliver on a government commitment to sustainability. Related to these trends, urban regeneration has been caught up in the wider ‘new urbanism’ movement that emphasises high-quality design and well-planned spaces (see Chapter 6). Another important new element in discussions of regeneration is the desire to create more ‘resilient’ cities which are better able to cope with the shock of changes to the wider economy and environment. In the aftermath of the 2008 credit crunch and ensuing financial crisis, questions of resilience have gained a new importance (as will be discussed in Chapter 8).

From boom to bust

One of the challenges of studying urban regeneration is that it is not an isolated process. Cities are affected by wider economic, political and environmental factors. The fortunes of cities are tied to the fortunes of nations and, ultimately, the global economy. This has a much longer history than simply considering the credit crunch of 2008 and its after-effects. Over the course of the twentieth century, cities in the Western world suffered from the loss of traditional indu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Acronyms

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Policy Framework

- 3 Governance

- 4 The Competitive City

- 5 Sustainability

- 6 Design and Cultural Regeneration

- 7 Regeneration Beyond the City Centre

- 8 Scaling Up

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- References

- Index