![]()

1

Introduction to the Discipline of Geomorphology

Kenneth J. Gregory and Andrew Goudie

The word geomorphology, which means literally ‘to write about (Greek logos) the shape or form (morphe) of the earth (ge)’, first appeared in 1858 in the German literature (Laumann, 1858; see Roglic, 1972, Tinkler, 1985). The term was referred to in 1866 by Emmanuel de Margerie as ‘la géomorpholgie’; it first appeared in English in 1888 (McGee, 1888a,b) and was used at the International Geological Congress in 1891 in papers by McGee and Powell. The term came into general use, including by the US Geological Survey, after about 1890, and it received wide currency in Mackinder’s lecture to the British Association meeting in Ipswich in 1895 when he referred to ‘what we now call geomorphology, the causal description of the earth’s present relief’ or the ‘half artistic, half genetic consideration of the form of the lithosphere’ (Mackinder, 1895: 367–379). The International Geographical Congress in London in 1895 had a section entitled Geomorphology, and A. Penck used the term in his paper to the meeting (Penck, 1895; Stoddart, 1986).

Although the late 19th century was when geomorphology was defined, the subject of study was recognizable much earlier (Tinkler, 1985) being significantly influenced by developments such as those in stratigraphy and uniformitarianism in geology and evolution in biology. Although there were many origins in geology, it became more geographically based with the contributions of W.M. Davis (1850–1934) who developed a normal cycle of erosion, suggested that it developed through stages of youth, maturity and old age, conceived other cycles including the arid, coastal and glacial cycles, and proposed that landscape was a function of structure, process and stage or time. His attractive ideas dominated geomorphology for the first half of the 20th century and arguably provided a foundation for later work and also encouraged debate by stimulating contrary views. Although alternative approaches, such as those by G.K. Gilbert, were firmly based upon the study of processes rather than on landform evolution, for the first half of the 20th century the influence of Davisian ideas ensured that geomorphology emphasized the historical development of landforms because the cycle of erosion introduced by Davis was appealing in its simplicity.

From its 19th century foundations geomorphology has developed enormously as reflected in the chapters in Section 1 of this book, including the history of geomorphology (Chapter 2), explanation (Chapter 3) and theory (Chapter 4), followed by geomorphology and environmental management (Chapter 5), and society (Chapter 6). This introduction focuses on the emergence and growth of the discipline, and then outlines the context of tensions, debates and issues that have arisen, many of which are elaborated in subsequent chapters.

EMERGENCE OF THE DISCIPLINE

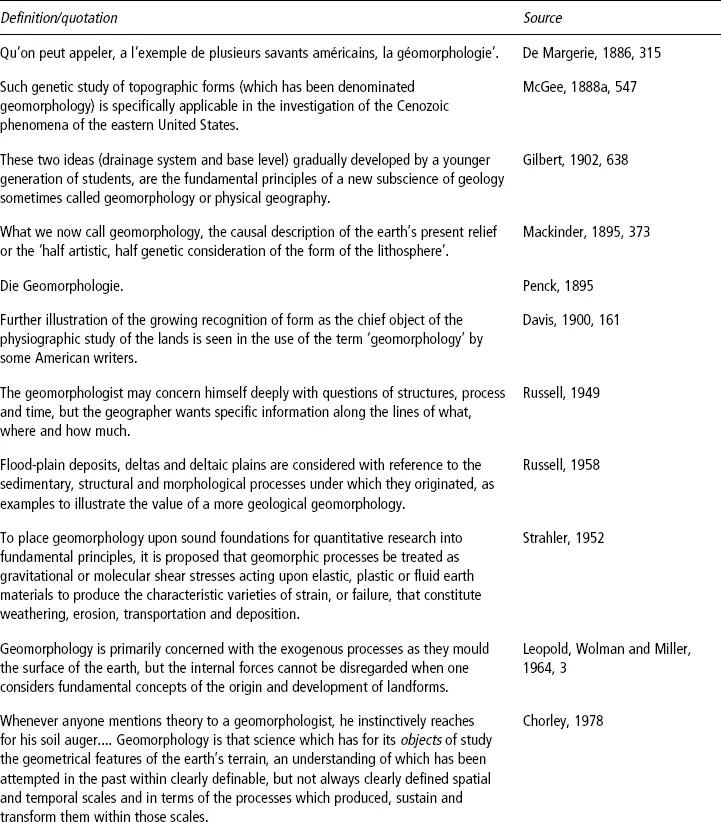

It is possible to see how definitions of, or comments on, the scope of geomorphology (Table 1.1) reflect the way in which the discipline of geomorphology emerged and was established. Until 1900 many early definitions saw geomorphology as being concerned with description of the Earth’s relief or with the form of the land (Table 1.1). However, according to Kirk Bryan (1941), Davis attempted to subdivide geomorphology as the genetic description of landforms into geomorphogeny, concerned with the history, development and changes of landforms, and geomorphography, concerned with their description. This distinction was not adopted (see Beckinsale and Chorley, 1991: 107) and indeed Davis preferred the term physiography, although he used the term geomorphology in an identical way. However, the distinction between the description of landforms and their development was identified by Russell (1949, 1958) who contrasted geographical with geological geomorphology (Table 1.1). In 1958 Russell commented that

geomorphology has not developed as substantially as Gilbert forecast in 1890. Physiography concentrated on problems of erosion, almost to the exclusion of other parts of the discipline, and developed a terminology which became elaborated beyond usefulness. Disregard of the third dimension and inadequate geophysical backgrounds led to unrealistic results by physiographers.

Table 1.1 Some definitions of geomorphology

Despite the approach of G.K. Gilbert, it was not until the mid 20th century that processes shaping the land and landforms gained prominence, as articulated by Strahler (1952) in dynamic geomorphology, and reinforced by Leopold, Wolman and Miller (1964) in their book Fluvial Processes in Geomorphology. These two contributions were outstanding stimuli for the instigation of process geomorphology. Strahler (1952) suggested that there were two quite different viewpoints of geomorphology, namely dynamic (analytical) and historical (regional) geomorphology which became associated with timeless and timebound perspectives. Also in the second half of the 20th century investigations into the Quaternary became more prominent. Whereas, previously, historical geomorphology had been focused on denudation chronology and especially on the morphogenesis of tertiary landscapes, investigation of contemporary glacial, deglacial and periglacial processes gave a significant stimulus to the investigation of Quaternary glacial systems, and this was further stimulated once investigations could be anchored to improved Quaternary dating using isotope stages.

A further strand was the inception of theory in geomorphology, crystallized by Chorley (1978), including his frequently cited comment that ‘whenever anyone mentions theory to a geomorphologist, he instinctively reaches for his soil auger’ (Table 1.1). Definitions used by two important texts in the 1980s reflected the multi-disciplinary nature of geomorphology (Selby, 1985) and the expanding horizons, to include non-terrestrial parts of the earth’s surface and the potential inclusion of other planets (Chorley, Schumm and Sugden, 1984) (Table 1.1).

Although Baker and Twidale (1991) regretted the dominance of process geomorphology and pressed for a more holistic view (Table 1.1), further adjustment was achieved as a consequence of the advent of plate tectonics in the 1960s. Continental drift had long been acknowledged as a tectonic basis for geomorphology, and endogenic processes had been shown to be significant in studies over the past century (Haschenburger and Souch, 2004). However, the fundamental importance of plate tectonics was subsequently reinforced by geochronological techniques including cosmogenic dating methods. This reinvigorated geomorphology, so that Summerfield (2005a) saw two scales of geomorphology: small-scale process geomorphology contrasting with macroscale geomorphology reflecting advances made by researchers outside the traditional geomorphological community. However, Summerfield (2005a) sees the potential for links between these two groups of researchers, countering (Summerfield, 2005b) the view that the growing role of geophysicists could lead to a reduced role for geographical geomorphologists as visualized by Church (2005). Summerfield (2005b) believes that ‘there is enormous scope to advance geomorphology as a whole probably at its most exciting time since it emerged as a discipline’. This has to cope with the advocation of earth system science (see Clifford and Richards, 2005) from which geomorphology could emerge at the centre of a group of new kinds of science (Richards and Clifford, 2008, see Table 1.1).

This therefore presents a paradox. On the one hand throughout the gradual emergence and broadening definition of geomorphology it is understandable why ‘geomorphology is, and always has been, the most accessible earth science to the ordinary person: we see scenery as we sit, walk, ride or fly. It is part of our daily visual imagery ...’ (Tinkler, 1985: 239). On the other hand, despite this accessibility and centrality, the discipline of geomorphology ‘remains little known and little understood, certainly in relation to other academic disciplines, and especially outside university circles’ (Tooth, 2009). Thus a discipline that should be very familiar is insufficiently known, although there is considerable potential to build upon the heritage and focus which differs from, and complements, other geosciences.

The discipline that emerged over more than a century, as expressed in the definitions and comments in Table 1.1, is now poised to develop further as a result of the techniques now available. Such emergence has effectively taken a century or so and during that time books published (Table 1.2) have reinforced the construction of the discipline, many aspects of which are discussed in a recent international encyclopedia of geomorphology (Goudie, 2004). Four substantial histories of the study of landforms have been published (Chorley et al., 1964, 1973; Beckinsale and Chorley, 1991; Burt et al., 2008) together with other perspectives including those of Davies (1968) and Tinkler (1985). Other books are referred to in Table 1.1 but particular ones collected in Table 1.2 exemplify seven themes. First were reactions to Davisian ideas: although credited with over 600 publications, Davis did not publish a book with geomorphology in the title so that Geographical Essays (1909) and his book in 1912 were his major works, and his ideas were conveyed in numerous articles. Although Davisian ideas were arguably the single most influential theory in geomorphology from the mid 20th century onwards (Tinkler, 1985: 147), they were challenged, amended and resisted by proffered alternatives (e.g. Hettner, 1921; Gregory, 2000). This second group included Penck’s Die Morphologische Analyse published in 1924, a significant alternative to the Davisian approach to geomorphology which did not become widely known in the English-speaking world until it was available in translation in 1953 (Czech and Boswell, 1953). Third were textbooks necessary to establish the foundations, and books with geomorphology in the title included those by Wooldridge and Morgan (1937), Worcester (1939), Lobeck (1939), von Engeln (1942) and Thornbury (1954), although others that were influential had alternative titles such as Physiography (e.g. Salisbury, 1907). Whereas such texts endeavoured to present a perception of geomorphology as a whole, a fourth group offered a particular approach which may have been regional (e.g. Cotton, 1922), climatic (e.g. Tricart and Cailleux, 1955, 1965, 1972) or founded upon an alternative cyclic approach (e.g. King, 1962). A fifth group was made up of books which concentrated upon techniques (e.g. King, 1966) or upon processes (e.g. Ritter, 1978), whereas a sixth group comprises more recent texts (e.g. Chorley, Schumm and Sugden, 1984; Selby, 1985; Summerfield, 1991). In addition to these, a seventh group comprises those which cover the history of geomorphology (Chorley et al., 1964, 1973; Beckinsale and Chorley, 1991; Burt et al., 2008).

GROWTH OF THE DISCIPLINE

The growth of the present discipline over the last century was considerable, and is reflected in the creation ...