![]()

PART 1

Setting the Context

![]()

Introduction

Colleen McLaughlin

Background

The two named authors of this book have worked for many years on the accredited programme for developing counsellors to work therapeutically with children and adolescents at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Colleen McLaughlin worked for twenty-six years on this and Carol Holliday for fifteen. This is important because this book represents what both have learned from this educational journey. The other authors in this book are either part of the team who work on the programme, past students, or supervisors.

Purpose

The book is about working therapeutically with children and young people in educational and related settings. It is aimed at a specialist audience of therapists and counsellors who work, or are learning to work, with young people and those who are employed in such settings. It is now recognised that working with children requires particular skills and understanding, that this cannot be a simple transfer of knowledge and capacity from working with adults or from training to work with adults. In this book we aim to: give a comprehensive theoretical base, which we feel is highly necessary in the field; to engage with the practice of psychotherapeutic counselling; to explore the contextual and professional issues of working in a school setting; and to illustrate these matters with case vignettes of work with children in school settings delivered by highly experienced practitioners. A key feature of this book is its focus on the conceptual base for therapeutic work, and on working specifically with children and young people in educational and related settings, and especially the role of the creative arts in working with children and young people (i.e., the use of play, story and other methods of working through metaphor and imagery).

Theoretical base

There are four concepts that shape our approach. These are:

1. An ecological or ecosystemic view of child development This means that we engage in looking at and suggesting that the counsellors or therapists should work in the wider contexts, as well as take account of them. The ecological approach signifies that not only do counsellors have to take account of the impact of the local and distal influences on a child’s development, but also that they should engage in working with these fields as well. This is different from a strictly clinical model where the work is mainly on the client and the therapy room. If counsellors adopt the wider approach, the ensuing professional issues are likely to be complex, and there is likely to be an array of these. These issues are discussed later in the book, especially Chapters 1 and 10 to 13.

2. A developmental approach There is an entire section that examines the implications of working with young people who are growing and developing fast. Therefore Part 2 (Chapters 2 to 5) examines child development theory in some detail and draws out the implications for practice.

3. A pluralistic or integrative approach (i.e., one that draws on various theoretical bases in a coherent and constructively critical fashion). An integrative approach has many elements. It takes account of all aspects of human functioning – the emotional, the behavioural, the cognitive, the bodily, and the spiritual. All of the theoretical positions and bodies of work that focus on these aspects are taken into account. It views human beings as having all the elements and needing to integrate them, so that therapy is about this process of integration: it is also the task of the therapist to integrate their approach and their understanding, so here you will find theoretical accounts that rely on the psychodynamic, client-centred, behaviourist, cognitive, family therapy, Gestalt therapy, body-psychotherapies, object relations theories, psychoanalytic self-psychology, and transactional analysis approaches, together with systems perspectives. Each approach is viewed as giving a partial explanation of behaviour, and each is enhanced when selectively integrated with other aspects of a therapist’s approach.

4. A relational view of therapy This is, finally, what the therapeutic process is based on. By this is meant that the therapeutic relationship is seen as central to the process of healing and working therapeutically. This is because, as Carol Holliday states, ‘There is now overwhelming evidence that the quality of the therapeutic relationship generally, and of the alliance in particular, is a predictor of therapy outcome (Norcross, 2002; Cooper, 2008; Haugh and Paul, 2008). The better the quality of the relationship, the more likely the therapy is to have a successful outcome. A strong relationship predicts success and a weak relationship predicts premature ending of the therapy’. It is also because of the developmental focus of this approach and the emphasis on attachment.

These core concepts are interrogated both theoretically and practically within the book. They also drive its organisation into four parts:

• Part 1: Setting the context

• Part 2: Understanding and working with the developmental tasks of childhood and adolescence

• Part 3: Working therapeutically with children and adolescents in schools

• Part 4: Professional issues in counselling with children and adolescents

Counselling and therapy in educational and related settings

This book also focuses on therapeutic work in educational and related settings. As is explored in Chapter 1, there is a history of counselling in schools but increasingly schools are being seen as particularly effective places for therapeutic and developmental work. (The Welsh government, for example, has a large-scale strategy for this.) Schools are appropriate sites because they have a consistent view of each child over time and they are also linked to the communities in which children live and grow. Therapeutic work in these settings raises many professional and ethical issues that are fully examined in the final part of the book, as well as in Chapter 11.

Working with children and young people, as well as in schools, has many implications for theory and practice (i.e., that children are not autonomous, don’t necessarily communicate their emotions verbally, and have strong connections to others who have responsibility for them and influence their development). The approaches to working non-verbally with children are examined in detail, as are the ethical, relational and practical aspects. Our aim is to offer as fully as possible all the theoretical, practical and professional aspects of therapeutic work with children and young people in educational settings.

The concepts and issues we discuss are illustrated and illuminated by case material throughout. All the contributors to this book have many years of psychotherapeutic experience to draw on, however, we would also acknowledge the complex ethical considerations that publishing work of this nature raises. The case vignettes, unless otherwise stated, are composite and draw on many cases whilst conveying examples of the kinds of issues that can arise in work with children and adolescents. The stance we have taken is to heavily anonymise the material so that individuals are unrecognisable and no person should be able to recognise him- or herself, and hence the examples offered contain no identifying features.

![]()

| ONE | The Child, The School, Counselling and Psychotherapy |

Colleen McLaughlin

Introduction

This chapter discusses the relationship between the child, the school and counselling, drawing upon an ecological approach. We argue that counselling involves taking account of and engaging with the family, the school and the wider community, as well as the child. Research on the emotional wellbeing of children and adolescence is examined and its connections to the ecological framework explored, together with the ensuing implications for the role of the school and counselling. The final section looks in more detail at the role of counselling in schools, including describing the history of counselling therein, and the evidence for its effectiveness.

The ecological or ecosystemic approach

Human beings create the environments that shape the course of human development. Their actions influence the multiple physical and cultural tiers of the ecology that shapes them, and this agency makes humans – for better or for worse – active producers of their own development. (Bronfenbrenner, 2005: xxvii)

This quotation from Bronfenbrenner contains many of the key ideas in his ecological theory, namely that development is a dynamic process of exchange between persons and their environments, we have agency as human beings, and human relationships matter. Urie Bronfenbrenner, who studied child development, children and their families, and was the co-founder of Head Start in the USA, brought together the work of Kurt Lewin (who saw behaviour as the result of an interaction between the person and their environment) and Lev Vygotsky (who emphasised the interaction between child and adults in learning) to shape his ecological systems theory of development. Bronfenbrenner was interested in the influences in a child’s life and development, and the interplay that existed between the complex systems of relationships that formed the surrounding environment. He suggested that there were critical factors in each child’s development, and these were the context, time, process, and the individual’s personal attributes. In doing this he was challenging the then practice of only studying ‘the strange behaviour of children in strange situations with strange adults for the briefest possible periods of time’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1974: 3). He saw the environment as a nested and interconnected system, similar to a series of Russian dolls, at the heart of which was the child or individual. This person would possess developmentally important personal attributes that invited, inhibited or prevented their engagement in a sustained and progressively more complex interaction with, and activity in, the immediate environment (Bronfenbrenner, 2005: 97).

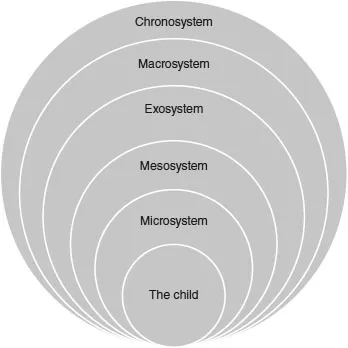

The remaining systems are both near and far, but all of these will influence a child’s development. As is shown in Figure 1.1 the nearest is the microsystem, and this consists of the child’s immediate environment (i.e., the family, school, peers, and the immediate neighbourhood). The second system, the mesosystem, often defines and constrains the microsystem: this is the culture or subculture of the family or the school. The third system is the exosystem, which in turn influences the previous two systems: this is the wider social context of the government, the education system, the economic systems, and the religious system. The final and most distant system is the macrosystem, which is the overarching ideology and legal system. These more distal systems clearly influence the child’s immediate environment. Lastly, the chronosystem is the dimension of time. What we are concerned with in this chapter is the emotional ecology of each child and adolescent in school, and how this ecology works to influence children’s wellbeing and development.

The emotional ecology of child and adolescent wellbeing

The topic of how society, and schools in particular, influence adolescent wellbeing is a large one, and as such it is not possible to cover this fully in one chapter (although Chapters 5 and 6 explore some aspects further). Adolescence is a unique time in the life-course because there is such huge growth and development. It is the transitional period between childhood and adulthood, and as transitional periods are a time when individuals are more sensitive to environmental inputs these assume a critical role (Mulye et al., 2009: 8). Recent research on adolescent wellbeing in the UK does however tell us something of how the systems around the microsystem work together. The Nuffield Foundation (2012; see also Hagell, 2012) has recently completed a major programme of research reviews examining how young people’s lives have changed since the 1970s, and whether these could further inform our understanding of the increase in adolescent mental health problems that has occurred in the last thirty years. The main social trends identified in the UK included:

• Increases in the proportion of young people reporting frequent feelings of depression or anxiety. This figure doubled between the mid-1980s and the mid-2000s. For boys aged 15 to16, rates increased from approximately 1 in 30 to 2 in 30. For girls they increased from approximately 1 in 10 to 2 in 10.1 (Collishaw et al., 2010).

• Increases in parent-rated behaviour problems: for example, approximately 7 per cent of 15 to 16 year olds showed high levels of problems in 1974, rising to approximately 15 per cent in 1999 (Collishaw et al., 2007).

• A similar rate of increase in ‘conduct disorders’ (mainly non-aggressive antisocial behaviour like lying and theft) for boys and girls, and for young people from different kinds of background.

• Encouraging signs of a levelling-off in these trends post-2000. For example, there was no rise in the level of emotional problems such as anxiety and depression amongst 11 to 15 year olds between 1999 and 2004 (Maughan et al., 2008). However, there are hints that the rates of some of the underlying causes might climb with the rise in youth unemployment and growth in poverty after the 2008 financial crisis and policy responses (Nuffield Foundation, 2012: 1).

The macrosystem level was seen as having growing influence and an area for increasing research. The school was described as a key social institution, as was the family and part-time employment. The key social trends identified as affecting young people’s wellbeing were: how they spent their time; education; shifts in substance use; and changes in family life. Young people spend much more time in education nowadays and this has been accompanied by a collapse in the youth labour market, especially since 2008. By 2000 the majority of young people were in full-time education rather than work. These factors affect how they experience many things and the nature of their time use. Larson et al. (2002) have highlighted some of the differences in the nature of the experience. So, for example, in work a young person is likely to experience authority and hierarchy in a different way from that of education and as a result will learn different things. They are also spending much more time with their peer group in educational settings. In addition, the nature of school experience has also changed over the last twenty years: for example, there has been a growing emphasis on testing and attainment, more participation in examinations, and young people are staying on at school longer. How these trends impact upon their wellbeing requires further work, but there are different implications for different groups. The trend towards more time being spent in education means having a different structure to the day, and young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) are those with the least structure. The implications for wellbeing of less interaction with adults, due to less time in work environments, of less structure, more unstructured time and more peer interaction, merit further research. However, we do know that there is a need for a clear structure from education to work, for managed transitions, and that this is not a straightforward pathway in our society. Transitions can be a time of vulnerability for young people, and especially for those who are most vulnerable, and in this case that encompasses those who are without education or employment (the NEET category).

Bronfenbrenner (2005) showed that factors interact and in this way the changes in how time is spent will be affected by other trends. Substance use has also altered amongst young people. There is greater availability of alcohol and other drugs, and yet there is also some evidence that levels of consumption have decreased recently. However, absolute levels of alcohol use amongst 11 to 15 year olds are higher than in most other countr...