![]()

1

Policy and Agency Contexts

National occupational standards

This chapter will help you meet the following National Occupational Standards for Social Work:

Key Role 5: Manage and be accountable, with supervision and support, for your own social work practice within your organization. Unit 15: Contribute to the management of resources and services.

Key Role 6: Demonstrate professional competence in social work practice. Unit 19: Work within agreed standards of social work practice and ensure personal professional development.

It will also help meet the following National Occupational Standards for Mental

Health:

- Identify trends and changes in the mental health and mental health needs of a population and the effectiveness of different means of meeting their needs (SFHMH 50).

- Negotiate and agree with stakeholders the opportunities they are willing to offer to people with mental health needs (SFHMH 72).

- Assess the need for, and plan awareness raising of mental health issues (SFHMH 87).

- Work with service providers to support people with mental health needs in ways which promote their rights (SFHMH 3).

Learning outcomes

- To increase your knowledge of mental health policy, mental health providers and organizational change.

- To develop your skills relating to the management of change – both self and others.

- To develop your practice working in agencies.

Introduction

All too often social workers will become immersed in practice without fully understanding the crucial policy and agency contexts which will inform and shape judgements made with and about clients and their families. In this early chapter we want you to take a step back from your busy workload and consider how policy making is determined, and then delivered, by the agencies you work in. The chapter begins with a brief overview of key debates about how UK social and health policies are understood and constructed. The sections which follow then focus on particular aspects of mental health policy, beginning with an account of the competing explanations for the rise of the Victorian asylum and the impact these institutions had on patients and professionals and wider society and then noting some of this period’s enduring legacy for contemporary policy and practice. The chapter then describes and analyses the key policy themes which are now identified with the period of ‘de-’ or trans-institutionalization that has occurred in the UK in the last two decades. It then provides a broad overview of key policy themes that re-emerge in the chapters on practice later in the book. These include community-based mental health care, risk management, prevention, empowerment and recovery. We describe and analyse the way in which these policy drivers determine the types of organizations in which mental health social workers are employed and the services that are provided to people with mental health problems. The chapter concludes by arguing that competent, reflective practice is underpinned by a critical awareness of the links between policy drivers, organizational form and social work practice.

Social work and social policy in the UK

For mental health social workers, who have their every working day filled with case load pressures, it can be difficult to understand how and why health and social care policies shape practice. We argue that a core understanding of ideological positions taken about policy-making processes is crucial to the profession.

Disagreements as to what constitutes good policy or social work practice are rooted in differing values, ideas, and problem definitions. Attempts to penetrate dominant ideas are important in that they force social policy analysts and social work practitioners to ask fundamental questions about possible future developments. (Denny, 1998: 27)

Although it is tempting to view policy making in terms of logical, linear processes, invariably it is the product of competing pressures and contested perspectives in which powerful discourses and constituencies are at play (Lister, 2010). For example, Clarke (2004) explains how the welfare bureaucracies that were constructed during the post-war settlement in the UK were critiqued and redesigned by successive Conservative governments to fit with discourses about new types of welfare delivery with a greater involvement by the market. This new mixed economy of welfare was further refined by subsequent Labour administrations.

Whilst acknowledging that these policy processes are indeed complex, this should not prevent attempts to explore how they function and the way they relate to everyday social work practice. Weiss et al. (2006) have developed a pedagogical model to consider how such questions can be answered when encountered by social work students. They argue that students should have a good knowledge of fields related to social structure and social policy and they should also acquire analytical skills exploring the dimensions of the links between social policy and the goals and values of social work. In addition students should be capable of undertaking a critical examination of social policy and its impact on social work practice. There are many aspects to this interface between social work and social policy; here are a few questions specifically about health and social care policies and the various implications these may have for your clients:

- Family policy – how do such policies differentially affect men and women?

- Welfare rights policy – why is there an increasing use of means tested benefits?

- Housing policy – can you explain the reduced levels of social housing?

- Community care policy – how well does policy and law deal with the burden of care?

- Criminal justice policy – why has there been a shift towards restorative justice practices?

Change and continuity: the origins of mental health policy in the UK

As with generic health and social care policies there is also a need to critically analyse mental health policy. We can understand how mental health policy has developed by examining the many political, social and economic factors that have converged and coalesced at different periods in the history of the UK state. Given the complexity of these events and processes it is not surprising that there are a number of competing histories that seek to explain how and why mental health policies developed in the way that they did (Rogers and Pilgrim, 2009). A particularly influential set of discourses that supported the rise of the Victorian asylum was informed by liberal, Enlightenment ideas that viewed these institutions in terms of a necessary reform of pre-capitalist forms of care and treatment for ‘the insane’ (Jones, 1960). This positive view of the asylum emerges in historical and contemporary arguments in support of the benefits that psychiatric institutions could deliver both then and now. For example, Borthwick et al. (2001) compare the principles which underlay ‘moral treatment’ by Tuke in the early nineteenth century with those that underpin contemporary mental health policy two centuries later. Other, less favourable commentaries position the rise of the asylum alongside the political economy of capitalism (Scull, 1977) and with it the need to control and manage deviant behaviours (Foucault, 1975). At its most coercive, the state had sought to incarcerate and thus used a range of physical, psychological, and latterly medical forms of care and treatment that appear harsh and unforgiving in the light of history. Aspects of this history remain with us today, whether in the physical imagery of surviving Victorian hospitals or in the way the state uses mental health laws to deprive service users of their liberty (a discussion that we will have in the next chapter).

We want to encourage you to think about this notion of the enduring historical legacy of mental health policies and consider how, sometimes surprisingly, this past still has a resonance for contemporary practice. So, consider the following two questions:

In completing this exercise you may think, as we do, that there are a mixture of possible responses, positive as well as negative. Hundreds of Victorian asylums were built in Britain and Ireland in the nineteenth century. Those that remain continue to be a brooding presence in many towns and cities, instilling fear amongst those citizens who are old enough to remember the hospitals when they were fully functional. For some patients, especially those who were incarcerated for long periods, the institution and its members (including professionals) may have been viewed, on balance, in terms of a collective ‘good’, offering protection, care and safety from the outside world. Each member of the institution knew and recognized the expected roles and relationships (see our discussion of the work of Goffman in Chapter 3). For others, the asylum was essentially oppressive, where rights and dignity were stripped away, professional power could not be challenged and there was little prospect of returning to the community outside the asylum. Institutionalization describes the largely negative impact of long-term institutional care in which people were rarely asked to make decisions, had little responsibility and spent most of their time relatively under-stimulated and inactive. Other histories also suggest that life outside the asylum could be just as coercive (Bartlett and Wright, 1999).

It is not easy to establish those moments when mental health policy significantly shifted in ways that dramatically affected the lives of service users, carers and professionals (Carpenter, 2009). Often these processes could be slow burning, erratic and hard to determine, but the history of mental health services in the UK can be roughly divided into three main phases: before 1845 when there was little formal system of care; between 1845 and 1961 when the asylum dominated; and from 1961 until the present with the development of contemporary practices of community care. Before the relatively progressive thinking that was embodied in the 1845 Lunatics Act, which compelled county authorities to establish asylums, people with mental health problems had mainly been subjected to arbitrary, haphazard and often brutal treatment in workhouses, prisons and private madhouses (Pilgrim and Rogers, 1993). Leading up to this legislation there was growing political and public awareness of the lack of mental health services and a number of innovative approaches had attempted to provide more humane care (Jones, 1998). Urbanization, industrialization and professional forces contributed to these changes but in the direction of segregation (Scull, 1977). Following the 1845 Act, the large Victorian asylums totally dominated mental health care until the first official discussions about moving towards community care began following the aftermath of the First World War. A Royal Commission (1924–1926) considered reform and recommended a community service based on treatment in people’s homes. Its recommendations were included in the Mental Treatment Act of 1930. Over the next 30 years some progress was made through open door policies, a greater focus on acute care, outpatient clinics, increased public awareness and the development of therapeutic community ideas. However, it was not until the 1950s that the role of institutions as the base for care was first really challenged. Jones (1998) has described this time as involving three revolutions – legal, social and pharmacological. Another factor was the spiralling costs of maintaining the mental hospitals.

The legal revolution began in the early 1950s with a growing concern about the loss of liberty involved in institutional care. This concern led to the creation of another Royal Commission in 1954 whose work was to form the basis of the 1959 Mental Health Act. This legislation confirmed the need to re-orientate mental health services away from institutions towards care in the community. The social revolution was heralded by the publication of a World Health Organisation report in 1953 that offered a new model for the development of community mental health services. In the late 1950s and early 1960s a rush of literature that confirmed the detrimental effects of institutionalization reinforced the need to move towards community-focused services.

The World Health Organisation report was closely followed by the pharmacological revolution that introduced new drugs which alleviated some of the symptoms of mental health problems. Although there was initial optimism about these drugs, their role in deinstitutionalization has perhaps been overplayed. By 1961 Professor Morris Carstairs noted that ‘few would claim that our current wonder drugs exercise anything more than a palliative influence on psychiatric disorders. The big change has been rather one of public opinion’ (Jones, 1998: 150). The in-patient population in England and Wales had peaked in 1955 at 155,000 and due to the legal, social and pharmacological developments began to decline slowly, with some community services introduced in rather piecemeal ways across the UK. However, in 1961, Enoch Powell, the new Minister for Health, driven by a political desire to reduce public spending (rather than any more therapeutic motive) declared in his famous Water Tower Speech the intention to attempt to cut the number of psychiatric beds by half in 15 years. This announcement established the pattern that has caused many of our current difficulties – the reduction of hospital beds without the establishment of sufficient community services to support people. Subsequent policy approaches highlighted this concern. Warnings about pursuing dehospitalization without reprovision were identified in ‘Better Services for the Mentally Ill’ (DHSS, 1975) and by the Social Services Committee of the House of Commons (1985) who stated,

A decent community-based service for mentally ill or mentally handicapped people cannot be provided at the same overall cost as present services. The proposition that community care should be cost neutral is untenable ... Any fool can close a long-stay hospital: it takes more time and trouble to do it properly and compassionately. (cited in Mind, 2010: 1)

A key theme that has influenced policy in this area throughout the developed world has therefore been the stated intention by governments to move patients from psychiatric hospitals and into the community (even though these concepts in themselves can be hard to define). There are disparate views on which factors can best explain the origins and delivery of these policy agendas, with Scull, in particular, questioning the conventional wisdom that the introduction of new psychotropic drugs in the mid to late 1950s enabled the trend towards rehabilitation in the community to take place. Yet it was not until the 1980s that such a policy began to be only partially recognized. Debates continue about the merits of hospital- and community-based forms of care, confirmed in Thornicroft and Tansella’s (2004) review of the evidence. A key factor in assessing mental health systems is the resources available to governments. Where there are limited resources, the literature suggests that investment should take place at the level of primary care. When more resources are available then policy makers are more likely to move away from asylum-based care. This usually happens when governments release funds by engaging in a process of deinstitutionalization. When welfare regimes can afford a stepped care model then important planning and training processes are necessary for successful outcomes. The authors conclude by arguing that a false dichotomy which poses institutional versus community care is not borne out in the evidence and that a pragmatic, integrated approach is necessary in any modern system of mental health care.

Deinstitutionalization and community care

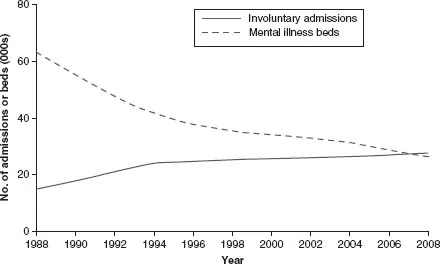

Service users, carers and mental health social workers have to deal with the consequences of this policy, however ill defined it remains. Although there has been a substantial reduction in hospital bed numbers, rates of detention remain high, as illustrated by the graph below taken from McKeown et al.’s (2011) paper on trends in hospital use in England from 1998–2008:

Figure 1.1 Trends in hospital use in England from 1998–2008

Similar trends occurred in Scotland and Northern Ireland, although services are inevitably configured in nuanced ways,...