![]()

| PART ONE | Theory and Research |

![]()

| ONE | Theories of Career Decision Making |

In this chapter and the next we discuss some of the theories that attempt to describe and explain how careers develop. This chapter covers theories that deal primarily with the ways people make career decisions, and these tend to focus on the initial entry to work. As we shall see, though, some of these theories also include propositions about later career development. First we examine person–environment fit theories, concentrating particularly on John Holland’s work. We then move on to look at developmental approaches, Donald Super’s theory being the most well-known example. Structural theories are then briefly discussed, before considering theories which use an interpersonal level of analysis to understand career development and decision making. Throughout the chapter the implications of the various theories for career counselling are considered.

Person–Environment Fit Theories

The idea of person–environment fit (or the degree of ‘congruence’ or ‘correspondence’ between workers and their environments) has been the main framework for understanding occupational choice and career decision making over the last century. One of the earliest attempts to describe what happens when individuals choose occupations was that of Frank Parsons, who, in 1908, established his vocational guidance agency in Boston, US. The theory which guided his work consisted of three propositions (Parsons, 1909): people are different from each other; so are jobs; and it should be possible, by a study of both, to achieve a match between person and job. The main implication of these statements for career counselling, of course, is that reliable and valid data are needed about individuals and jobs. Over the following decades, these data were gathered in the form of tests of aptitudes and interests, and also analyses of the skill and interest requirements of occupations.

Person–environment fit approaches to career counselling, therefore, emphasise diagnosis and assessment, and the usual outcome is a recommendation to the client on an appropriate course of action. The practitioner is likely to use questionnaires and inventories completed before the interview (or series of interviews) as aids to assessment.

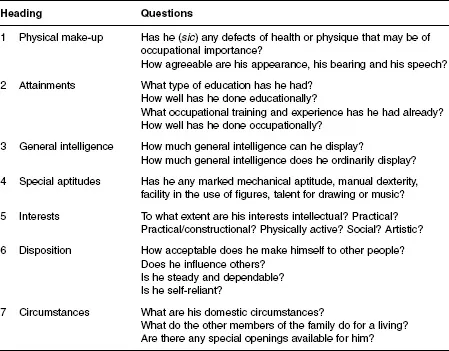

In the second half of the twentieth century, a commonly used framework for diagnosis, assessment and recommendation was Rodger’s Seven-Point Plan (Rodger, 1952). This is simply a list of questions to address in the interview, organised under seven headings. The headings and their associated questions are shown in Table 1.1.

For many years, this was the main model used by careers advisers working with school leavers. It has fallen out of use in recent years, however, largely because of its diagnostic and directive nature and its perceived rigidity. However, many practitioners value the aide-mémoire provided by the seven headings.

A much more elaborate theory of person–environment fit was developed in the United States by Holland in the 1960s and 1970s. The most recent version of his theory is set out in his 1997 publication (Holland, 1997). It has been labelled ‘differentialist’ in that it focuses on individual differences, characteristics that distinguish individuals from others. Holland proposed that people seek occupations that are congruent with their interests (defined as preferences for particular work activities). The most important tenets of the theory are that:

Table 1.1 Rodger’s Seven-Point Plan

Source: adapted from Rodger (1952: 8–16)

- People and occupational environments can be categorised into six interest types: realistic; investigative; artistic; social; enterprising; and conventional.

- Occupational choice is the result of attempts to achieve congruence between interests and environments.

- Congruence results in job satisfaction and stability.

Holland’s six types are as follows:

- Realistic – likes realistic jobs such as mechanic, surveyor, farmer, electrician. Has mechanical abilities, but may lack social skills. Is described as: asocial, conforming, hard-headed, practical, frank, inflexible and genuine.

- Investigative – likes investigative jobs such as biologist, chemist, physicist, anthropologist. Has mathematical and scientific ability but often lacks leadership ability. Is described as: analytical, cautious, critical, curious, introspective, independent and rational.

- Artistic – likes artistic jobs such as composer, musician, stage director, writer. Has writing, musical or artistic abilities but often lacks clerical skills. Is described as: emotional, expressive, intuitive, open, imaginative and disorderly.

- Social – likes social jobs such as teacher, counsellor, clinical psychologist. Has social skills and talents, but often lacks mechanical and scientific ability. Is described as: co-operative, empathic, sociable, warm and persuasive.

- Enterprising – likes enterprising jobs such as salesperson, manager, television producer, buyer. Has leadership and speaking abilities but often lacks scientific ability. Is described as: adventurous, ambitious, energetic, sociable, self-confident and domineering.

- Conventional – likes conventional jobs such as book–keeper, financial analyst, banker, tax expert. Has clerical and arithmetical ability, but often lacks artistic abilities. Is described as: careful, conscientious, inflexible, unimaginative and thrifty.

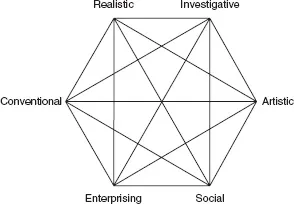

Holland (1985a) set out a hexagonal model of occupational interests where some of the six types are seen as more similar, while others are more distantly related. This model is described in Figure 1.1, with types at adjacent angles more closely related than those at opposite angles.

A number of instruments have been developed to assess Holland’s interest types. These include the Vocational Preference Inventory (Holland, 1985b), the Self-Directed Search (Holland, 1985c, and available at http://www.self-directed-search.com) and the Strong Interest Inventory (Harmon, Hansen, Borgen & Hammer, 1994).

Figure 1.1 Holland’s hexagonal model for defining the psychological resemblances among types and environments and their interactions

Source: Holland (1985a)

One obvious implication of Holland’s theory for career counselling is that practitioners can help clients assess their interests and work environments and understand relationships between them. Simply developing cognitive structures or frameworks with which to view themselves and occupations is helpful for many people. Some career counsellors organise and reference their career and occupational information according to Holland’s types, using a three point code corresponding to the most prominent types. This facilitates the process of matching interests and environments.

Holland’s main proposition, that individuals make occupational choices that are congruent with their interests, has generally been supported by research (see, for example, Spokane, 1985). However, other work has cast some doubt on his assertion that congruence results in satisfaction and stability (Tinsley, 2000; Tranberg, Slane & Ekeberg, 1993). (The relationship between job satisfaction and congruence, for example, appears to be rather weak, in the order of 0.21.) This may be because people are now more likely to think about what job they want, rather than what occupation suits them, and that occupational titles are inadequate descriptors of work environments (Arnold, 2004). Furthermore, some writers have questioned the validity of the six-fold model of interests. Prediger (2000), for example, has argued that two dimensions of ‘people’ versus ‘things’ should be incorporated into the model.

Subsumed under the umbrella title ‘person–environment fit’ is a wide range of other theories. These include the Minnesota theory of work adjustment (Dawis & Lofquist, 1984), which focuses on the abilities used at work and the rewards sought from it, and Schneider’s attraction-selection-attrition (ASA) model (Schneider, Goldstein & Smith, 1995), which sees fit as a consequence of individual recruitment and selection and subsequent adjustment to the organisation. The ASA model proposes that organisations can be defined by the characteristics of people working in them. Through a process of attraction, people are attracted to organisations whose members they resemble; through selection they are recruited into posts where they will fit in; and through a process of attrition people who do not fit in leave.

Person–senvironment fit theories have generally found some support (Tinsley, 2000), but the evidence for the validity of Holland’s theory is somewhat weaker. This may be because Holland’s model oversimplifies the idea of fit; it does not take enough account of the fit between abilities and the demands of work; and it does not pay enough attention to reciprocal influences between individuals and work environments (how work affects individuals and how individuals affect work). As Tinsley (2000) has argued, further research into fit models should take account of conceptual links between interests, values and personality. Other work suggests that models of fit should include abilities also. Ackerman and Heggestad (1997), for example, in a review of studies assessing relationships between abilities, interests and personality, provide evidence for the existence of four clusters of traits across these three domains. These are: social; clerical/conventional; science/maths; and intellectual/cultural. All the clusters include traits across the three domains, apart from the social cluster. The authors suggest that: ‘Abilities, interests and personality develop in tandem, such that ability levels and personal dispositions determine the probability of success in a particular task domain and interests determine the motivation to attempt the task’ (Ackerman & Heggestad, 1997: 239). This suggests that career counsellors should use frameworks of fit which integrate the domains of abilities, interests and personality.

Present status models

Research into person–environment fit has not given much attention to the probability that certain types of work environment are instrinsically more congenial and satisfying than others. What have been called ‘present status’ models of relationships between job characteristics and outcomes predict that work environments will affect workers in a uniform way, irrespective of individuals’ desires and abilities. Warr (2002) argues that the desirable characteristics of work environments include environmental clarity and feedback, variety, level of pay, physical security, externally generated goals, interpersonal contact, opportunity for skill use, opportunity for control and valued social position. These present status models may be just as valid as person–environment fit models, as well as more parsimonious.

Interests and personality

Researchers have also studied relationships between Holland’s occupational interests and other models of personality. Toker, Fischer and Subich (1998) have provided a useful review of this research. There is now some agreement that personality can reliably be described in terms of five broad dimensions (the ‘Big Five’): extraversion; neuroticism; openness to experience; conscientiousness; and agreeableness (e.g. Matthews & Deary, 1998). These are defined as follows:

- Extraversion – the extent to which the individual is sociable and outgoing. Extraverts enjoy excitement and may be aggressive and impulsive.

- Neuroticism – the extent to which the individual is emotionally unstable. Those high in neuroticism can be tense and anxious, with a tendency to worry.

- Openness to experience – the extent to which the individual is imaginative and flexible, having a positive, open-minded response to new experiences.

- Conscientiousness – the extent to which the individual is well-organised, planful and concerned to achieve goals and deadlines.

- Agreeableness – the extent to which the individual is good-natured, warm and compassionate in relationships with others.

Toker et al. (1998) reported that the most consistent links between interests and personality are positive associations between openness (being responsive to new experiences and ideas) and investigative and artistic interests, and between extraversion (being outgoing and sociable) and enterprising and social interests.

However, others have argued that personality is likely to make an independent contribution to work outcomes, regardless of fit. For example, Jepsen and Sheu (2003) found that congruence between occupational interests and environments was unrelated to job satisfaction, yet workers in Social, Enterprising and Conventional occupations reported higher satisfaction than those in Realistic jobs. As Hesketh (2000) suggests, one explanation for this is that Social and Enterprising Holland types are likely to be extraverts, that extraverts are on the whole happier than introverts, and therefore extraverts are likely to be more satisfied in any occupation. This may also be because extraverts are more prepared to take steps to improve their jobs to suit themselves. The contribution of personality to career attitudes and outcomes is further supported by a recent study by Bozionelos (2004), which showed that personality plays an important role in career success, particularly intrinsic career success (individuals’ subjective satisfaction with career and broader life issues). Those with agreeable personalities displayed greater intrinsic career success, while those high in neuroticism were less satisfied with their careers and with life generally.

The person–environment fit approach to career counselling has often been stereotyped as assuming that the career counsellor’s role is simply to offer advice based on expert knowledge of the client and of work opportunities. It has also been criticised as focusing on occupational choice as a one-off event, ignoring the processes leading up to a career d...