![]()

Section 1 Developing Critical Reflection

This section of the book considers a number of key interrelated themes. These include the way that a contemporary professional practitioner in ECEC needs to adopt a reflective stance in order to support children and families. In order to illustrate the interrelated themes, we have taken an unusual approach of presenting two case studies of student journeys through higher education so the reader can clearly see how their critical reflective thinking has developed over the course of their study and the impact this has had on their practice with children and families.

The section begins with a view of the importance of critically reflective study and considers how a developing practitioner engaged in study needs to see features of ECEC as interconnected and part of a whole rather than separate aspects of professional working. This can be seen clearly in Chapter 1 from Michael Reed, Rosie Walker and Linda Tyler. They ask the reader to consider ways of examining the chapters in the book critically and provide a framework to help you do this as you read through the book. The authors suggest this will reveal interconnected issues that can be used as part of your studies and in assignments.

The section moves on to present a chapter from Karen Hanson and Karen Appleby, which attempts to define and unpack the term reflective practice and underline its importance to the practitioner. They suggest that reflection aids their thinking and practice. The next chapter by Sue Callan builds on the need for reflection and introduces the concept of the ethical practitioner and provides a deconstruction of what this means. It also provides a theoretical position which suggests ethical reflection is an essential component of critical thinking. The chapter by Jennifer Worsley and Catherine Lamond that follows underpins the need to view critical thinking as a process that develops as you progress through your studies. They suggest it is a process which is valuable when used in collaboration with others – an important part of critical thinking. The final chapter by Michelle Rogers introduces the need to engage purposefully when using and learning from new digital technologies. She argues this too is part of reflective practice and has an essential part to play in the way you study and view the digital world that will inevitably change over the period of time you are engaged in study.

A Collective Position

The collective position or argument contained in this section is quite clear. Critical reflection on practice leads to critical awareness. When this is seen in the context of being an ethical practitioner it leads naturally towards the way practice-based research should encompass these elements as it shapes an evaluation of practice which is able to explore and even determine what quality looks like. The key questions are, do these facets of critical engagement make a difference and have an impact upon practice? Can they and have they actually been adopted by those engaged in a programme of study leading to a degree or professional qualification?

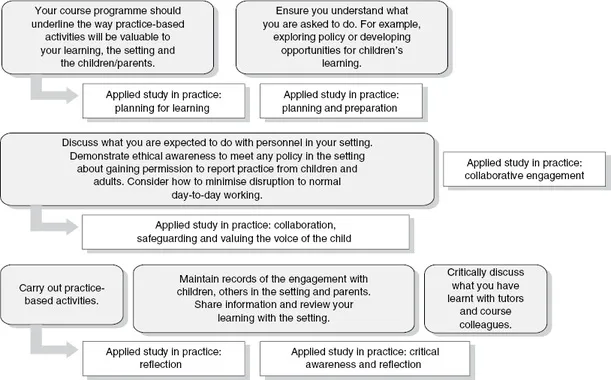

Figure S1.1 shows the key questions which are discussed with students as they prepare and engage in work-based inquiry. It is a model underpinned by the premise that a student who engages in practice-based inquiry considers what they are researching and why this is important in order to develop their thinking and knowledge. They should integrate ethical protocols into all aspects of practice and ensure that any form of inquiry has a defined purpose that should be valuable to the setting, children and families. In addition, the process should actively engage the setting in what goes on. It should recognise sound practice but go beyond simply accepting the information presented and consider ways to explore and critically examine practice. As a consequence of these actions it is possible to argue that they are shaping the practice environments that they inhabit. The aim is to develop research processes so that students are involved in real world collaborative inquiry as a means to elicit views on what is happening and what works on the ground (Reed, 2011). However, to make this work and meaningful in practice requires personal and professional characteristics (Potter and Quill, 2006; Messenger, 2010). For example, a recognition that they (as persons who are an integral part of the ECEC setting and therefore insiders) are accountable to others in the workplace and are motivated to engage ethically and rigorously in their investigations. To look at what works as well as issues that need attention, where appropriate through an appreciative form of inquiry (Cooperrider, 2005), they must also be able to share the findings of their inquiry honestly with others and reflect and learn from the process. Such characteristics which form an essential component of the researcher in practice resonate with the established discourse on leadership and practice-based research. Hallet (2013), for example, provides a perceptive view of the strategic and pedagogical leadership role in improving and shaping practice. She argues this involves leadership and learning by establishing a learning culture in which learning, knowledge and pedagogy are highly visible within an organisation. This feature was also identified as an essential component of leadership in the Effective Leadership in the Early Years Sector (ELEYS) Study (Siraj-Blatchford and Manni, 2007). This study investigated leadership in the early years sector (ECEC), identifying fundamental requirements for leadership for learning which included an understanding of the context within which any impact of change would take place, a commitment to collaboration and a purposeful desire to improve quality. The work of Rodd (2006) also suggests that the research process can clarify and initiate issues for change. Similarly a paper by Raelin (2011) contends that the role of the researcher is to provide tools to encourage the observed to be part of the research dialogue and part of the inquiry itself. Moreover, the researcher should recognise and share the results of their practice-based inquiries with others in the setting. In effect doing what a report from Developing Excellence in Practice-based Research in Public Health (Potter and Quill, 2006: 17) sees as a key leadership component, which is to develop and encourage interactive forums across disciplines and institutions; an action which may be seen as forging communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) because the researcher is working with others in order to find solutions to issues relevant to their own settings and communities.

Figure S1.1 Developing learning and confidence in practice

To develop this idea we ask you to consider the words and actions of two professional colleagues who have made this journey of reflection and critical awareness. Both are recent former students who agreed to become the focus of a case study designed to illustrate the impact of critical reflection on their own practice. Their views underpin why the chapters in this particular section and within other parts of the book should be seen as important facets of ECEC quality and practice. We are grateful for their co-operation and indebted to the way they have honestly and carefully shared their views and ideas. Making the journey through higher education is a process that, as developing practitioners, it is important to embrace and trust, even though at times, like all important journeys, it can seem a struggle.

The Professional and Personal Journeys of Two Practitioners

Both entered higher education to complete a degree programme leading to a BA (Honours) in Early Childhood Studies. They can be described as capable and conscientious individuals who held values and beliefs which motivated them to gain professional qualifications and enter a profession which values children's learning and seeks to protect the welfare of children. (Values and beliefs embedded into the chapter by Sue Callan about understanding the importance of a sound ethical position are transposed into practice by Carla Solvason (Ch. 25) when she suggests the need to hold such values as part of a desire to engage in purposeful research in practice.)

Both colleagues engaged enthusiastically in their studies and were introduced to the idea of developing reflective and critical thinking via lectures, seminars and directed reading. (Something that the Editors see as fundamentally important, which is why the chapter on reflective practice by Karen Hanson and Karen Appleby is placed early on in this book.)

They were encouraged to reflect about their feelings as ‘student practitioners on placement’ as they experienced being part of a good quality early childhood setting. They reflected on what they had learnt, what key questions emerged and what they might use to enhance future placement opportunities. (A sign that professional development and being a developing professional is important, which is taken up in the chapter by Mike Gasper later in the book.) They both felt this allowed them to develop a view about the value of reflective practice, as one remarked: ‘it took some time to actually get it’, and went on to explain how it was important to develop a means of reflecting on practice, for practice and in practice. They both indicated how it was necessary to draw together facets of ECEC practice and reflect upon the non-visible features such as taking an ethical stance, being part of a professional community and developing the ability to view children and families holistically. They explained this view in terms of the way their course had asked them to see children and families in the context of their own social world, their community, their culture, heritage and family. They needed to accept difference and diversity and to accept that society and the way we view children's development may change and become refined through research and knowledge. This is not to say that they were accepting of everything they were exposed to as part of their training. They were challenging what they were reading and learning and seeing in practice. They described this ability to challenge as a process that required support and help from tutors and they said how they needed help to critically reflect. This process mirrors the issues that Jennifer Worsley and Catherine Lamond describe in their chapter. Importantly, they felt that this allowed them to see the importance of a less visible feature, which was responding positively to change. Not just change in curriculum design or changes in policy and regulatory aspects of practice, but also the way they were able to recognise changes in their own values, beliefs and competencies. An example was the way they both reported how they perceived themselves as advocates for children in terms of safeguarding their welfare and in practical terms about the way they developed expertise in using information technology and how they were embracing new technology. Indeed, they were keen to point out how online learning had enhanced their studies and felt that they had developed ‘a positive ICT attitude’ which meant feeling comfortable with the way technology aided communication and the way families were using technology with their children. This is a point that Michelle Rogers underlines in her chapter exploring the world of ICT and practitioner learning.

This positive responsiveness to change is illustrated in the way their degree programme spanned a time when there was considerable change being proposed and enacted by the UK Government about professional qualifications in ECEC. In particular, this was reflected in the need to ‘professionalise’ and enhance the quality of ECEC practitioner training. The result was a new Government initiative (in England) which encouraged practitioners to gain Early Years Professional Status (EYPS). This status required substantial evidence of practice ability across the 0–5 age range in terms of meeting required standards ev...