- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Modern Pig Farming

About this book

This book contains a classic guide to pig farming that presents the reader with all the fundamental information they would need to know abut keeping and breeding pigs for pleasure or profit. It covers every aspect of the subject from stock selection to common ailments and how they can be avoided, making it ideal for novice breeders and owners alike. "The Handbook of Modern Pig Farming" is not to be missed by collectors of vintage agricultural literature. Contents include: "Type And Breed", "Laying The Foundations Of The Herd", "Systems Of Running", "Breeding Sows", "The Sow And Litter To Weaning", "Housing", "Feeding Stuffs", "Elastic Rations", "Feeding Home-Grown Produce", "Hygiene", etc. Many vintage books such as this are increasingly scarce and expensive. It is with this in mind that we are republishing this volume now in an affordable, modern, high-quality edition complete with a specially-commissioned new introduction on pig farming.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Modern Pig Farming by H. M. Rikard-Bell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technik & Maschinenbau & Öffentliche Landwirtschaftspolitik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

TYPE AND BREED

THE barren lands, high and rocky, are not the only portions of the farm suitable for pig breeding. Admittedly it is better for one’s housing to be established on rising ground, but any site on which water does not lie after rain will do. In other countries where there is not such diversity of terrain, quite flat ground is drained and utilised with success.

In countries in the Northern Hemisphere it is preferable that buildings should face the south, while, in southern climes, a northern aspect is desirable, the important thing being that as much sunlight as possible will penetrate as far as possible into the piggery itself, as this is the best of all disinfectants, as well as being the great provider of life and health. Should one feel any doubt of the beneficial effect on all forms of life of the direct rays of the sun, it should be enough to state that in cold, dark winters “bottled sunlight” in the form of cod-liver oil will clear up, and eradicate, many of those worrying but undiagnosable ailments so loosely grouped under the heading of “cramp.”

Take it, then, that a piggery should be placed on land as well drained as possible, where it will receive the maximum of sunlight, and I think one is quite justified in omitting all the finicky details with which the over-conscientious adviser would burden us.

In a later portion of this book the question of housing, yarding, etc., will be dealt with fully, but one must not forget the old adage about “first catch your bird.” Let us then deal with the animals themselves.

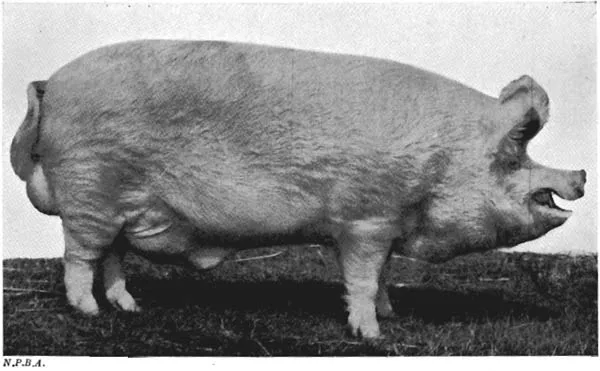

In America and in Australia the Tamworth is still favoured as a sire, but even in these two countries prejudice and preference are giving place to the proven value of the Large White as the begetter of bacon pigs.

England, Denmark, Scandinavia, Jugo-Slavia, Germany, and the rest advocate the exclusive use of the Large White as the top cross for the economical production of bacon.

Although bacon competitions, carcass cups, and other trophies have been won by such extremes of breed as pure Tamworth, pure Berkshire, and pure Large Black, a casual glance would show that an overwhelming percentage of the winners have had the Large White as the sire, either winning with pure breds or crosses. The time will come here, as in Denmark, when any other sire for the production of bacon will be illegal, and until that time has come let us take a leaf from their book and take this one big step towards uniformity in the carcass we turn out, and let us—albeit against some of our sentimental leanings—utilise this boar exclusively.

One of the most eminent of practical pig men in the world, Gray of Australia, has advocated the use of the Tamworth-Berkshire-Comeback; others plumped for the Tamworth on a Large White or on a Middle White sow, but it will be noted that in all more recent writings they advise this same big step towards uniformity.

Take it, then, that the Large White is our sire. He is tremendously prepotent, of a fertile and prolific breed himself, usually docile and easy to handle, and his progeny can never be guilty of “seedy-cut,” as the black markings on the belly are known.

A point worthy of remembering, and proved equally true with other branches of livestock, is that one should avoid a very heavy boar for the service of small maiden sows. On the other hand, it has always been found best to use a matured animal for producing second, third, and subsequent litters; a young boar being kept for gilt service.

The choice of one’s sows immediately brings forward the contentions of the various breeds. Let us consider them, or the main ones, with impartiality, both from the viewpoint of bacon production and that of pork production.

SIRE OF THE WORLD’S BEST BACON

BOURNE KING DAVID, LARGE WHITE BOAR

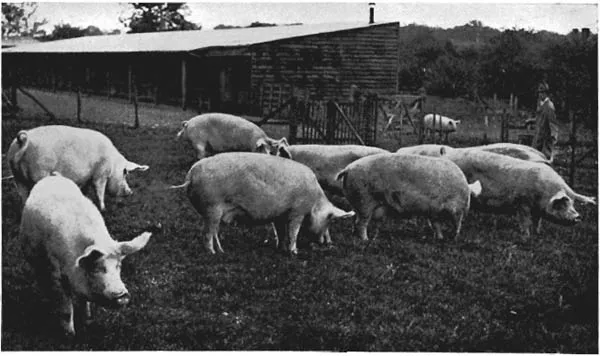

SUMMER COMFORT

A PRIZE-WINNING GROUP OF LARGE WHITE SOWS FROM THE STEVENTON HERD

Our first requirement is that a breed shall be of high fecundity; that it shall not only drop large litters, but that its milking ability will wean a very high proportion of them at a profitable weight; that the mother will be tractable and easy to handle during those difficult weeks when her litter is suckling.

Immediately these breeds come to one’s mind—the Saddlebacks, the Large Black, the Welsh, and the Large White. Without splitting hairs as to which of them has the final decimal point’s advantage over the others, we can take it that they average about 10.5 born and 8.5 reared to eight weeks.

These figures show a decided advantage over such others as the Berkshire, Middle White, and Tamworth, which seldom average 9 born, 7 reared. These figures are taken for the whole of the breed kept in all manner of conditions, in all types of country throughout the British Isles, and isolated records are for the purpose of this book ignored, it being taken for granted that the “passenger” who cannot rear more than three or four pigs serves to balance out the grand old matron who drops fifteen and rears most of them every time.

Now from the point of view of bacon production the claims of the fine shoulder and great depth of chest of the Tamworth cannot be ignored, just as the tendency of the Large Black to become a little too heavy forward, after it has passed six months of age, must be offset against its fertility. The Tamworth, on the other hand, comes to bacon weight a little later than some of the other breeds, and it is very doubtful if in practice its slightly superior grading will offset the price of the extra food consumed.

For outdoor conditions the Tamworth and the other four breeds are eminently suitable, grazing contentedly and turning the grasses into profit with very little fear of any ill-effects from so rigorous an existence.

Intensively, however, it has been found that both the Large Black and the Tamworth, and to a lesser extent the Wessex Saddleback, chafe at confinement, and are seldom seen with the bloom of the Large White.

One very outstanding advantage in using Large White sows is that one is able to retain one’s own selected gilts for breeding, without having to indulge in the expense of the upkeep of other than the Large White boar, or, alternatively, replacing ageing sows from outside sources. The thing is—is the Large White sow the equal of the Wessex Saddleback and the others; and, secondly, is it to one’s advantage to have pure-bred stock instead of crosses?

To answer the first question one has only to check up on carcass competitions, to find that pure-bred Large Whites win even more than the remainder of the breeds put together, grading well, giving highly satisfactory weight-for-age gains, and in general leading the show rings of this country at least by a fairly substantial margin over the other breeds and their crosses.

For example, at Smithfield Show, 1934, the Champion Plate for baconers was won by the Large White exhibit of Lord Daresbury, and at the Dairy Show the first five places in the Whitley Cup and the first three places in the Beale Cup were gained by this popular breed. Again, at the Royal Agricultural Show at Ipswich this breed completely swept the board in pure-bred classes, and against all comers produced the champion, bred by Mr. H. R. Davidson.

The long list of awards in the various competitions throughout the country over the last ten years show an absolute preponderance of Large White successes.

Every breeder demands hardiness in his pigs, and a breed which is able to thrive in Australia, the Malay States, India, and South Africa, where the summer temperature is almost as extreme as the cold in Russia, Finland, and northern Scandinavia, is surely sufficiently hardy for anybody. In all these countries the Large White has become the prime favourite. Additionally, practical breeders throughout the world have found the Large White to be very seldom attacked by cramp and its allied ailments, it being able to stand confinement better than any other type.

There has been, however, a strong advocacy for what is known as hybrid vigour, by which it is maintained that a first cross will “do” better and faster than either of its progenitors used solely. Just what extent of truth lies behind this is difficult to gauge. The only vigour in which the commercial breeder of bacon pigs is interested is that which causes the animal to gain good-grading meat quickly, with as small a percentage of bad “doers” and culls as is possible. Here, indubitably, the difference between the pure bred and the cross is negligible, for, on any well-run piggery, a minimum of one pound weight should be gained daily for the first six months of a pig’s life.

At what conclusion have we now arrived? That the Large White sow is the equal of the Wessex Saddleback and the Large Black when it comes to breeding and rearing big litters; that there can be no lack of uniformity by the little pigs throwing strongly to the breed of their mother, as is prone to happen with crosses; that for all practical purposes a pure-bred pig is at least the equal of a cross; and that, finally, the maintaining of a pure-bred herd reduces the number of boars kept to a minimum, and eliminates the passenger whose sole purpose is to get replacement gilts when some of the herd matrons must be cast for age.

So at the risk of alienating the sympathies of the champions of such fine breeds of pigs as the Welsh, the Essex and Wessex Saddlebacks, and the Large Black, I should strongly advise that the pure Large White be kept for bacon production, always bearing in mind that the type within the breed is as important as the actual breed itself.

However, there will be always those who consider that it is easier to breed to an ideal by crossing than it is to get rid of undesirable strains within one particular breed. For example, many Large White families have a tendency to thin bellies; some to thick shoulders; others, again, to deficient ham formation. Granted that any breed has its less efficient members and that one may like to use crossing to get at what the markets demand, I should like to make a few comments on various crosses and their desirability.

Outstanding in the world is the Danish baconer, mainly produced by crossing the Large White boar on to the Landrace sow. “Well,” cries the farmer, “let’s import these marvellous sows and steal the trade from the foreigner within a few years.” But it is not as simple as that. The Landrace is nothing out of the ordinary anyhow! Whether she is the original from which sprang the Welsh breed, or vice versa, will provide endless controversy; but, it must be admitted, the Danish Landrace is better on the average than the average Welsh. The Danes have practised recording, have utilised every statistical advantage to improve their breed, have developed their animals until we find that the true modern Landrace is nearer a cross between a Welsh and a Large White, and—bane of crossing—there are no throw-backs to one or the other parent breeds.

If it were possible, and it isn’t, to import Landrace stock into this country, I should be against it from the start. We have better stock here on the spot both for crossing and for the production of pure-bred baconers.

The Welsh, recorded and skilfully built up, can equal the Dane’s baconer with comparative ease. There are other crosses which can beat it.

To save argument and any ill-feeling as to the slight advantages of the one type over the other, we can class both the Essex and the Wessex as the Saddleback breeds and be done with it. This Saddleback will throw a better type of baconer than the Landrace does, and, where selection is keen, a fine type of blue-and-white animal is the result—a colour nearly as desirable as the white. The Saddlebacks, as a breed and not taking into account the deficiencies of individuals, have better shoulders than the Welsh or the Landrace; they have even better length; in early maturity, fecundity, and hardiness they are approximately equal. Now that the breed societies which sponsor our Saddlebacks are so much alive to the good points of the animals in which they are interested, we shall soon see recording and litter testing doing for these quaintly marked swine even more than the Dane has done with the Landrace.

Then one must not omit the Large Black from any crossing programme. This sow is, perhaps, the best mother of them all. She is a deep milker, docile, and thrifty. Her disadvantage is that unfortunate tendency towards heavy shoulders. Crossed with the right type of Large White boar, she is capable of producing an excellent carcass; generally Grade B. However, if one retains the gilts from this cross one finds that, when mated again to Large White, the mothering capability of the original dam is transmitted to her daughters, and a baconer that is quite up to standard will be produced from this second cross. Actually this is the most popular second cross of all.

To get a rapid result on the grading sheet with this Large Black sow one can use a Tamworth boar, but the red breed doesn’t seem to blend with the black quite as efficaciously as does the Large White, and one will find many more “sports.”

To my mind the cardinal principle in cross breeding is to utilise the sow to the best adva...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Contents

- Part I Breed and Management

- Part II Feeding

- Part III Hygiene and Disease

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Facts and Figures

- Index