- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

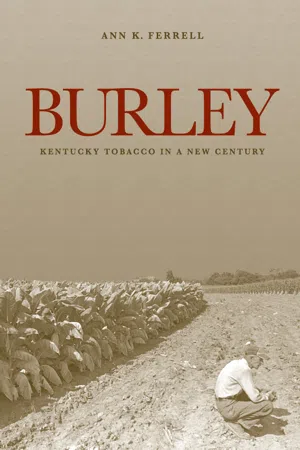

Yes, you can access Burley by Ann K. Ferrell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2013Print ISBN

9780813167589, 9780813142333eBook ISBN

9780813142340Part 1

The Burley Tobacco Crop Year, Then and Now

Introduction to Part 1

It's a late winter day in March 2007, and when Keenan Bishop, county extension agent, and I get out of my pickup truck at a Franklin County, Kentucky, farm, we are immediately encircled by two curious but friendly dogs, including a tiny dog I will come to know as Buster. We walk through a gate to where two men are working, and I meet Martin Henson for the first time, along with an older fellow helping him with the day's work. As we talk, Martin continues to work, and following Keenan's lead, I begin to help a little. What I didn't know at the time is that Martin would become central to my fieldwork and that the pattern of interaction with Martin, a pattern I would follow over the next year, was being set.

In part 1 of this book, I illustrate the tobacco year, describing the steps in the process of raising and selling a crop of burley tobacco, based on what I learned during my fieldwork in central Kentucky. My fieldwork began in 2005, but I spent the most time in the field as I followed the 2007 crop. I conducted recorded interviews and spent time with farmers (male and female), retired farmers, wives of farmers working off-farm jobs, county agricultural extension agents, university tobacco specialists, former and current warehousemen, and agricultural organization leaders. I was treated to numerous farm tours, which usually included inspection of the tobacco in whatever stage it was in at the time and often a comparative inspection of tobacco being raised on different farms by the same farmer; tobacco barns and stripping rooms; greenhouses, float beds, and plant beds; and sometimes equipment sheds. Many such tours included only the parts of the farm directly relevant to tobacco and not the spaces in which cattle grazed or were fed or where corn or other crops grew. I was invited to visit and observe—and at times participate—at crucial steps in tobacco production and marketing; attended events organized by farm organizations; and was generally welcomed into the farms, homes, and offices of many generous people. I was frequently fed dinner at midday and sometimes supper in the evening; the location depended on the role of women in the family as well as the intimacy of the relationship, with meals either in farm kitchens or at nearby convenience stores or restaurants.

I later realized that Martin Henson never gave me a farm tour. Instead, he served as my guide through the tobacco year—even as I worked with many others in the tobacco community—and so I saw his float beds as he prepared them and his stripping room when it was time to strip tobacco and so on.1 I also accompanied him as he fed his cattle, if I was there when it was time to feed the cattle. Martin welcomed me into the daily routine of the farm in a manner that allowed me to learn the details of raising a crop of tobacco as I needed to learn them but also to experience the rhythm of work on a tobacco farm, which most often also includes at the very least activities related to cattle, corn, and hay. Because Martin was a central figure in my learning process, he is also central to the following narrative I have constructed about the crop year.

That said, however, Martin's experiences and perspectives cannot be taken to represent the experiences and perspectives of anyone but Martin. One result of the many changes that have taken place in tobacco production and marketing is that, as tobacco grower Roger Quarles pointed out to me, it is now more difficult to describe a typical burley tobacco farmer. At one time, although there were certainly differences based on economic class and farm/land ownership, farmers largely faced the same issues, and their practices varied only marginally from farm to farm or county to county. Crop sizes certainly varied, but not widely as compared with today's variations. The current period of transition has brought with it much more variability, in part because acreage size directly relates to farm practices. Over the course of my fieldwork I met the spectrum of growers, from small growers who continue to do the bulk of the work themselves to growers of large acreages who, as one farmer described it, “never touch a stalk of tobacco.”

As retired tobacco farmer Jerry Bond told me, “Tobacco's commonly known as the ‘thirteen-month crop,’ because, most times you're still finishing one crop while you're starting the next year's crop—preparing the soil or the seed beds or whatever. You know you may be stripping tobacco, when you're starting the next one.” The chapters in part 1 follow the thirteen-month production cycle, highlighting changes that farmers described to me. During interviews, casual conversations, and situations such as farm tours, I was told not just about how tobacco work is done today. I was also told about how the work used to be done, about the changes that are currently taking place, and about the changes that could be seen coming down the pike. A prevalent stereotype about farmers is that they are resistant to change. This is a particularly widespread belief about tobacco farmers, because as the economic and political/social context of tobacco production has changed, public discourses have continually asked, “Why don't they just grow something else?” There are a host of reasons why just growing something else is not a solution for many tobacco farmers, and I will discuss some of these in this book. Here it is important to point out that many assume that tobacco farmers are simply unwilling to experiment with new ideas. The many changes that farmers have experienced that I describe in part 1 of this book—including many that farmers initiated—demonstrate that tobacco farmers are very open to new ideas, once it is clear that those ideas make sound economic sense in their specific circumstances.

Chapter 1

Sowing the Seeds and Setting the Tobacco

The work that Martin was engaged in on that March day when I first met him was the preparation of the beds in which his tobacco plants would germinate and grow. Because tobacco seeds are too delicate to plant directly in the field, they must be started in a protected environment and then transplanted. As we talked, he stretched thick black plastic across wooden frames built directly on the ground, weighted it down, and filled the plastic-lined frames with water. Later, he would plant seeds in polystyrene trays filled with peat-moss-based soil, and the trays—each about thirteen by twenty-six inches, with about 250 cells1—would then be set in the water to float in these float beds. Fertilizer would be added to the water and the beds covered at night and uncovered during the warm days of spring.

Before the 1990s, all growers started their tobacco plants directly in the ground in one-hundred-foot-by-twelve-foot plant beds. The preparation of the plant beds was a major task that evolved over the years but retained the same basic parameters: ground was cleared, weeds were killed, seeds were planted and covered, the beds were weeded, and the plants were individually pulled and transplanted into neat rows in the field. Since at least colonial times, through the 1950s and ’60s, tobacco beds were “burned,” which meant that burning wood or brush in some form was used to kill the weeds. Early on, burning logs were slowly rolled across the beds, and later, fires were built on metal frames that were then dragged across the beds, resting for a period on every part of the bed. Burning the beds was an event that took place either in the late fall or in the early spring, depending on the practices of a particular farmer. For the children in some farm families, burning the beds was an annual event to look forward to, as it meant staying up late to monitor and move the fires, perhaps roasting hot dogs and marshmallows. In the 1960s, it became common practice to gas the beds—the prepared plants beds were covered with plastic and gassed with a range of chemicals, the most popular and lasting of which was methyl bromide, which was sold in pressurized cans. Once the beds were treated for weeds, they were covered to protect the seeds as they germinated; they were fertilized and irrigated as they grew. Whether burned or gassed, some weeds would survive, and the task of weeding the plant beds without stepping on or otherwise harming the young tobacco plants was a dreaded job.

When it came time to set tobacco—as transplanting the young plants into the field is called—individual plants were pulled from these plant beds and brought to the field, either in baskets or wooden crates or wrapped in burlap bundles. Women often pulled plants as men prepared the ground for setting or started setting—one woman commented to me that it seemed like whenever there were plants to be pulled the men suddenly had ground that needed to be worked—but many people told me it was a job that “everyone” did. Pulling plants is often described as one of the worst aspects of tobacco work because it meant being bent over for long periods of time, trying to get through the bed without stepping on plants, which often meant perching precariously on a wooden board that was balanced across the bed. During a 2005 interview, Kathleen Bond described it vividly: “It's hot and you're like, either standing on your head or squatting down and, you know, neither one is comfortable and you have to—you can't like really walk out into the bed because you, you know, step on plants and ruin them and you have to—I don't know, it just, it makes you sore and the sweat's running in your eyes and deer flies get on your back and bite you.” By the late 1990s, the vast majority of farmers moved from plant beds to water beds or float beds.

The practices involved in starting the plants from seed provide one example of my statement that there is less typicality today. Many tobacco farmers have built greenhouses that house their float beds. Greenhouse float beds produce more usable plants. Robert Pearce of the University of Kentucky told me that according to results of university trials, greenhouse float beds yield about 95 percent usable plants, versus 80–85 percent in outside float beds. Martin estimated that he sees about an 85 percent success rate in his outside float beds. Although greenhouse float beds may have a higher success rate under ideal conditions, greenhouses are more expensive to build and maintain than outside float beds, and they introduce additional risks. Greenhouses provide opportunities for controlling the environment in which the plants grow, particularly the temperature, but heating and cooling systems must be carefully monitored in order to avoid temperature extremes. Greenhouses can also harbor diseases that can spread quickly through an entire greenhouse and possibly wipe out all the plants in it. Growers that I met had experienced such disasters firsthand. For all of these reasons, some growers have chosen not to grow their own plants and instead buy them from other producers. In one sense, this can be seen as a promising entrepreneurial opportunity for farmers as they adjust to the decline of tobacco markets, and many look for additional or new sources of income. On the other hand, the buying and selling of tobacco plants has been described to me as a practice that represents not only the changes that have taken place in tobacco production but the loss of the community both maintained and symbolized by reciprocal or swapping relationships between farmers.

By the late 1990s, the majority of growers raised their tobacco plants in float beds—with polystyrene trays floating in water—rather than in the ground. (Photo by author)

Many larger growers have built greenhouses in which to start their tobacco plants in float beds. (Photo by author)

However, because of the difficulty of the work involved in pulling plants, the transition to float beds was quite welcome. Martin told me this about his transition:

When I first started out, I was gonna try it, so I put out about a hundred trays. And at that time my wife, who's a nurse now [slight laugh], she was, that was before she was going to school. And this is back in the ’90s, early ’90s. I had plant beds and then I had these hundred trays, on water. Well, we pulled the plants, and then, when we got them done, we went to the water beds and, used them. She said “I'll never pull another plant” [laugh]. So I had to [laughing] make my water beds bigger, because I sure couldn't pull them.

The next year Martin planted all his plants in float beds. I've heard similar stories of rapid movement to float beds from other farmers. But even as I write about this in the past tense—because plant beds are talked about almost entirely in the past tense, as a practice of the distant past—I came to know one family who continues to raise half of their plants in plant beds and half in water beds. Marlon Waits, who raises burley tobacco with his brother and cousin, told me that they consistently see higher yields from plants started in the ground; plants beds “just seem to make a better plant,” he told me. I was told about other farmers who also continue to start some or all of their plants in the ground.

Prior to the 1990s, all growers started their tobacco plants in one-hundred-foot-by-twelve-foot plant beds. The Waits family continues to raise half of their tobacco plants in plant beds, as shown here. (Photo by author)

In addition to relieving the farmer from having to take the time or suffer the misery of pulling plants, the advantage of float beds is that fewer plants are wasted. When plants had to be pulled from plant beds, the morning was usually spent pulling plants, and the afternoon was spent setting them in the field. Each day, guesses had to be made about how many plants could be transplanted into the field that afternoon; few would survive for tomorrow if too many were pulled or if a storm came up. With the float bed method, the trays full of plants are simply pulled out of the water and loaded onto a wagon or truck still in the tray; any leftovers can be slipped back into the water.

Although seed is costly, it is common practice to sow more than a grower will need in preparation for the possible loss of plants due to disease or harsh weather conditions such as drought, frost, or hail. This was particularly true when plant beds were the norm, since plants were also lost if they were pulled and not used. If all went well, there would be plants left over after the crop had been successfully set in the field, which meant that if a neighbor ran into problems and needed more plants, surplus plants could be given to the farmer in need—literally a life-saving act when tobacco was the only source of cash for a farm family. According to Roger Quarles, who raises extra plants and sells them, “Customarily everybody put out their own tobacco beds and then if they, if for some reason theirs didn't do well or had bad luck or something—typically you'd go across to your neighbor, maybe he had some extra or something and there just, never was any charge.” He went on, “Occasionally you'd hear something like that, somebody charging for plants. And if they did they'd be talked about [slight laugh]. But then it became apparent that people didn't mind paying for them so it was a very quick shift.”

Robert Pearce, extension tobacco specialist in plant and soil sciences at the University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, told me:

It's kinda interesting—and this is just I guess sort of a social aside—is that before, when you had plants in beds, you'd go and you'd pull your plants and when you got done, you'd have extras—we seeded a lot more plants than we ever used in those days. And so, when you got done and a neighbor called up and said “I need some plants,” yeah, you know they'd just come over and pull them. You know, we didn't really think about plants having a value. Of themselves. And now the culture is that with these, with the greenhouse plants, they have a very real value and can be bought and sold and traded.

As Pearce, Quarles, and others have told me, float beds have dramatically changed the value of young tobacco plants, making them a commodity to be bought and sold. That farmer in need may now have to buy those plants from neighbors or from growers who can be located through the University of Kentucky College of Agriculture website. This change is seen by some as symbolic of the loss of the swapping relationships between farmers. Although this change may also signify a larger shift in communities more generally, it is seen by some tobacco farming families as a negative consequence of the move from plant beds to float beds even as they are thankful for the benefits of float beds.

Martin raised all his plants in the beds he was preparing that first day, enough to plant just over thirty thousand pounds of cured leaf (approximately fifteen acres), spread over three farms—the amount that he had raised for many years. When I say that Keenan and I “helped” on that first day, I mean small tasks like picking up a couple of pieces of wood from the back of Martin's truck to weight down the edge of the float bed liner and helping to stretch out the liner while Martin filled the beds with water. I later realized that what I didn't do was important; I didn't just stand and watch, distracting him from his work, expecting him to stop working while he talked to me. Instead, Keenan and I slipped into the rhythm of Martin's work, assisting in a minor way without being asked or asking. In two different contexts, Martin told me a story about him and his wife, Kathy's, first date, which they spent horseback riding on the farm. This version was recorded in a storytelling session that developed when Martin came back to the house as I was finishing an interview with Kathy: “She came out one evening, Sunday evening I believe it was or something, but anyway I loaded up some saddles and we went back there and the horses are back in the back. We got to this gate down here and, I pulled up there and, she sat there and, I got out, opened the gate, got back in the truck, pulled it up, got out, closed the gate, got back in the truck. I said, ‘Now girl, if you're gonna spend any time around here, whosever driving don't have to open and close the gate.’” At this point Kathy, who was not raised on a farm (and who, after several years of working the farm with Martin once they were married, went back to school and became a nurse), said, laughing hard, “I just sat there. I didn't know I was supposed to open the gate!” This brief narrative exemplifies Martin's expectation that anyone spending time with him on the farm needs to be able to anticipate basic tasks that need doing.

During my many visits to Martin's farm I assisted in small ways when I could, and he taught me to do some of the tobacco work, including setting, topping, and stripping. Hanging around with Martin as he worked meant learning to anticipate some small task—like opening a gate or hitching a trailer to his truck—that needed doing. Usually, not being a farm girl, I had never done these things, and I did my best at the tasks, hoping most of all to avoid embarrassment. Occasionally, however, I would have to ask him how to do something, and there went the rhythm of work and talk as Martin had to show me how to do whatever it was, always something that was second nature to him. In January 2008, as we pulled up to the barn in his pickup, just having gone through the main gate leading onto the farm, he again told me the story about Kathy and the gate—but he prefaced it with, “I'll tell you like I told Kathy…” Not understanding why he was telling me this story again, and why he was prefacing it in this way, I protested, “But I opened the gate!” and then immediately I realized that for some reason, on this occasion, I had asked as we pulled up to the gate, “Do you want me to open the gate?” instead of routinely opening it.

At other times, the rhythm of work and talk with Martin meant standing on the back of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Foreword

- A Note on Transcription

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1. The Burley Tobacco Crop Year, then and Now

- Part 2. The Shifting Meanings of Tobacco

- Part 3. Raising Burley Tobacco in a New Century

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index