- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fairy Tale as Myth/Myth as Fairy Tale

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fairy Tale as Myth/Myth as Fairy Tale by Jack Zipes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Folklore & Mythology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2013Print ISBN

9780813108346, 9780813118901eBook ISBN

97808131439101. THE ORIGINS OF THE FAIRY TALE

In his endeavor to establish the origins of the fairy tale for children, Peter Brooks stated that “when at the end of the seventeenth century Perrault writes down and publishes tales which had been told for indeterminate centuries—and would continue to be told, and would be collected in varying versions by the Grimm Brothers and other modern folklorists—he seems to be performing for children’s literature what must have been effected for literature long before: that is, he is creating a literature where before there had been myth and folklore. The act of transcription, both creative and destructive, takes us from the primitive to the modern, makes the stories and their themes enter into literacy, into civilization, into history.”1Indeed, almost all literary historians tend to agree with Brooks that the point of origin of the literary fairy tale for children is with Charles Perrault’s Contes du temps passé (1697);2 yet they never adequately explain why this came about in relation to the development of civilité3 and place too much emphasis on Perrault and his one volume of tales. Indeed, Perrault never intended his book to be read by children but was more concerned with demonstrating how French folklore could be adapted to the tastes of French high culture and used as a new genre of art within the French civilizing process. And Perrault was not alone in this “mission.”

Illustration by Walter Crane, 1875.

In order to comprehend the historical origin of the literary fairy tale for children and adults in France toward the end of the seventeenth century, we must shift the focus away from one author and try to grasp how many authors contributed to the formation of the literary fairy tale as institution. It was not Perrault but groups of writers, particularly aristocratic women, who gathered in salons during the seventeenth century and created the conditions for the rise of the fairy tale. They set the groundwork for the institutionalization of the fairy tale as a “proper” genre intended first for educated adult audiences and only later for children who were to be educated according to a code of civilité that was being elaborated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. But what does institutionalization of the fairy tale mean? What were the conditions during the seventeenth century that led aristocratic women for the most part to give birth, so to speak, to the literary fairy tale? These questions are important to address, if we want to understand our contemporary attitudes toward fairy tales and their seemingly universal appeal. As we shall see, their “universality” has more to do with the specific manner in which they were constructed historically as mythic constellations than with common psychic processes of a collective unconscious. Literary fairy tales are socially symbolical acts and narrative strategies formed to take part in civilized discourses about morality and behavior in particular societies and cultures. They are constantly rearranged and transformed to suit changes in tastes and values, and they assume mythic proportions when they are frozen in an ideological constellation that makes it seem that there are universal absolutes that are divine and should not be changed. To clarify how the mythization of fairy tales evolved, I propose to discuss first the significance of the institutionalization of the fairy tale and then to analyze how Beauty and the Beast has assumed mythic features during the past three hundred years.

The importance of the term “institutionalization” for studying the origins of the literary fairy tale can best be understood if we turn to Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garden.4 Bürger argues that “works of art are not received as single entities, but within institutional frameworks and conditions that largely determine the function of the works. When one refers to the function of an individual work, one generally speaks figuratively; for the consequences that one may observe or infer are not primarily a function of its special qualities but rather of the manner which regulates the commerce with works of this kind in a given society or in certain strata or classes of a society. I have chosen the term ‘institution of art’ to characterize such framing conditions.”5

The framing conditions that constitute the institution of art (which includes literature in the broad sense) are the purpose or function, production, and reception. For instance, Bürger divides the development of art from the late Middle Ages to the present into the following phases:6

Sacral Art | Courtly Art | Bourgeois Art | |

Function or Purpose | cult object | representational object | portrayal of bourgeois self-understanding |

Production | collective craft | individual | individual |

Reception | collective (sacral) | collective (sociable) | individual |

In the period that concerns us, art at the court of Louis XIV, Bürger maintains that art is “representational and serves the glory of the prince and the self-portrayal of courtly society. Courtly art is part of the life praxis of courtly society, just as sacral art is part of the life praxis of the faithful. Yet the detachment from the sacral tie is a first step in the emancipation of art. (‘Emancipation’ is being used here as a descriptive term, as referring to the process by which art constitutes itself as a distinct social subsystem.) The difference from sacral art becomes particularly apparent in the realm of production: the artist produces as an individual and develops a consciousness of the uniqueness of his activity. Reception, on the other hand, remains collective. But the content of the collective performance is no longer sacral, it is socialibility.” 7

If we examine the rise of the literary fairy tale during the seventeenth century in light of Bürger’s notion of institution, we can make the following observations. The literary fairy tale was first developed in salons by aristocratic women as a type of parlor game by the middle of the seventeenth century.8 It was within the aristocratic salons that women were able to demonstrate their intelligence and education through different types of conversational games. In fact, the linguistic games often served as models for literary genres such as the occasional lyric or the serial novel. Both women and men participated in these games and were constantly challenged to invent new ones or to refine the games. Such challenges led the women, in particular, to improve the quality of their dialogues, remarks, and ideas about morals, manners, and education and at times to oppose male standards that have been set to govern their lives. The subject matter of the conversations consisted of literature, mores, taste, and etiquette, whereby the speakers all endeavored to portray ideal situations in the most effective oratorical style that would gradually have a major effect on literary forms.

In the case of the literary fairy tale, though one cannot fix the exact date that it became an acceptable game, we know that there are various references to it toward the end of the seventeenth century and that it emanated out of the “jeux d’esprit” in the salons. The women would refer to folk tales and use certain motifs spontaneously in their conversations. Eventually, women began telling the tales as a literary divertimento, intermezzo, or as a kind of dessert that one would invent to amuse other listeners. This social function of amusement was complemented by another purpose, namely, that of self-portrayal and representation of proper aristocratic manners. The telling of fairy tales enabled women to picture themselves, social manners, and relations in a manner that represented their interests and those of the aristocracy. Thus, they placed great emphasis on certain rules of oration such as naturalness and formlessness. The teller of the tale was to make it “seem” as though the tale were made up on the spot and did not follow prescribed rules. Embellishment, improvisation, and experimentation with known folk or literary motifs were stressed. The procedure of telling a tale as “bagatelle” would work as follows: the narrator would be requested to think up a tale based on a particular motif; the adroitness of the narrator would be measured by the degree with which she/he was inventive and natural; the audience would respond politely with a compliment; then another member of the audience would be requested to tell a tale, not in direct competition with the other teller, but in order to continue the game and vary the possibilities for linguistic expression.

By the 1690s the salon fairy tale became so acceptable that women and men began writing their tales down to publish them. The most notable writers gathered in the salons or homes of Madame D’Aulnoy, Perrault, Madame de Murat, Mademoiselle L’Héritier, or Mademoiselle de La Force, all of whom were in some part responsible for the great mode of literary fairy tales that developed between 1697 and 1789 in France.9 The aesthetics developed in the conversational games and in the written tales had a serious side: though the tales differed in style and content, they were all anticlassical and were implicitly told and written in opposition to Nicolas Boileau, who was championing Greek and Roman literature as the models for French writers to follow at that time.10 In addition, since the majority of the writers and tellers of fairy tales were women, there is a definite distinction to be made between their tales and those written and told by men. As Renate Baader has commented:

While Perrault’s bourgeois and male tales with happy ends had pledged themselves to a moral that called for Griseldis to serve as a model for women, the women writers had to make an effort to defend the insights that had been gained in the past decades. Mile Scudéry’s novels and novellas stood as examples for them and taught them how to redeem their own wish reality in the fairy tale. They probably remembered how feminine faults had been revalorized by men and how the aristocratic women had responded to this in their self-portraits. Those aristocratic women had commonly refused to place themselves in the service of social mobility. Instead they put forward their demand for moral, intellectual, and psychological self-determination. As an analogy to this, the fairy tales of the women made it expected that the imagination in the tales was truly to be let loose in any kind of arbitrary way that had been considered a female danger up until that time. After the utopia of the “royaume de tendre,” which had tied fairy-tale salvation of the sexes to a previous ascetic and enlightened practice of virtues and the guidance of feelings, there was now an unleashed imagination that could invent a fairy-tale realm and embellish it so that reason and will were set out of commission.11

If we were to take the major literary fairy tales produced at the end of the seventeenth century—Madame D’Aulnoy, Les Contes des Fées (1697-98), Mademoiselle La Force, Les Contes des Contes (1697), Mademoiselle L’Héritier, Oeuvres meslées (1696), Chevalier de Mailly, Les Illustres Féés (1698), Madame de Murat, Contes de Féés (1698), Charles Perrault, Histoires ou Contes du temps passé (1697), and Jean de Prechac, Contes moins contes que les autres (1698)—one can ascertain remarkable differences in their social attitudes, especially in terms of gender and class differences. However, all the fairy tales have one thing in common that literary historians have failed to take into account: they were not told or written for children. Even the tales of Perrault. In other words, it is absurd to date the origin of the literary fairy tale for children with the publication of Perrault’s tales. Certainly, his tales were popularized and used with children later in the eighteenth century, but it was not because of his tales themselves as individual works of art. Rather, it was because of certain changes in the institution of the literary fairy tale itself.

Up through 1700, there was no literary fairy tale for children. On the contrary, children like their parents heard oral tales from their governesses, servants, and peers. The institutionalizing of the literary fairy tale, begun in the salons during the seventeenth century, was for adults and arose out of a need by aristocratic women to elaborate and conceive other alternatives in society than those prescribed for them by men. The fairy tale was used in refined discourse as a means through which women imagined their lives might be improved. As this discourse became regularized and accepted among women and slowly by men, it served as the basis for a literary mode that was received largely by members of the aristocracy and haute bourgeoisie. This reception was collective and social, and gradually the tales were changed to introduce morals to children that emphasized the enforcement of a patriarchal code of civilité to the detriment of women, even though women were originally the major writers of the tales. This code was also intended to be learned first and foremost by children of the upper classes, for the literary fairy tale’s function excluded the majority of children who could not read and were dependent on oral transmission of tales.

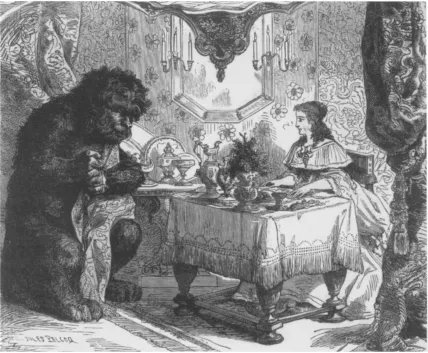

From Les Contes des fées offerts à Bébé, c. 1900.

Most scholars generally agree that the literary development of the children’s fairy tale Beauty and the Beast, conceived by Madame Le Prince de Beaumont in 1756 as part of Le Magasin des Enfants, translated into English in 1761 as The Young Misses Magazine Containing Dialogues between a Governess and Several Young Ladies of Quality, Her Scholars, owes its origins to the Roman writer Apuleius, who published the tale of Cupid and Psyche in The Golden Ass in the middle of the second century A.D.12 It is also clear that, in the system used by most folklorists to distinguish different types of tales, the oral folk tale type 425A, the beast bridegroom, played a major role in the literary development. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Cupid and Psyche tradition was revived in France with a separate publication of Apuleius’s tale in 1648 and led La Fontaine to write his long story Amours de Psyche et de Cupidon (1669) and Corneille and Molière to produce their tragédie-ballet Psyché (1671). The focus in La Fontaine’s narrative and the play by Moliére and Corneille is on the mistaken curiosity of Psyche. Her desire to know who her lover is almost destroys Cupid, and she must pay for her “crime” before she is reunited with Cupid. These two versions do not alter the main plot of Apuleius’s tale and project an image of women who are either too curious (Psyche) or vengeful (Venus), and their lives must ultimately be ordered by Jove.

All this was changed by Madame D’Aulnoy, who was evidently familiar with different types of beast/bridegroom folk tales and was literally obsessed by the theme of Psyche and Cupid and reworked it or mentioned it in several fairy tales: Le Mouton (The Ram, 1697), La Grenouille bienfaisante (The Beneficent Frog, 1698), and Serpentin Vert (T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Origins of the Fairy Tale

- 2. Rumpelstiltskin and the Decline of Female Productivity

- 3. Breaking the Disney Spell

- 4. Spreading Myths about Iron John

- 5. Oz as American Myth

- 6. The Contemporary American Fairy Tale

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index