- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Longest Rescue by Glenn Robins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2013Print ISBN

9780813166216, 9780813143231eBook ISBN

97808131432551

Unfortunate Sons

Late in the evening of 4 August 1964, President Lyndon Johnson appeared on television to inform the world of U.S. retaliatory strikes against North Vietnam in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incidents involving the U.S.S. Maddox and C. Turner Joy. “As I speak to you tonight,” the president announced, “air action is now in execution against gunboats and certain supporting facilities in North Vietnam which have been used in these hostile operations.” In concluding his brief remarks, the president stated, “Our response for the present will be limited and fitting.”1 Unfortunately for those involved in the mission, Johnson's irresponsible demand to appear on television before the end of the late-night news and “the final deadline for the major East Coast papers” eliminated the element of surprise.2 When the president addressed the nation, only four of the fifty-nine planes making up Operation Pierce Arrow were actually airborne, and those four were 350 miles from their targets. Among those yet to take off was Lieutenant (j.g.) Everett Alvarez Jr., a navy pilot. In a bizarre twist of fate, Alvarez had been part of the response to the alleged attacks on the Maddox and C. Turner Joy the previous night. He had dropped illumination flares for a fellow navy pilot, Commander James Stockdale, as they attempted to identify the two American ships and any would-be attackers.3

Called into action again, Alvarez was part of a squadron of A-4C Skyhawks “assigned to hit the naval base at Hon Gai harbor, about twenty-five miles northeast of Haiphong and only fifty miles south of the Chinese” border. Because of an eleven-hour time difference between Washington, D.C., and Hanoi, the bulk of the strike force launched during the afternoon hours of 5 August. At 2:30 P.M. local time, Alvarez was the first launch off of the U.S.S. Constellation. He reached his target seventy-five minutes later, only to discover that the “briefers had guessed” wrong and the torpedo boats were on the opposite side of the harbor. He made a second pass, and as he headed out over the southern edge of the town, he received fire on the port side of his windshield. Forced to eject, Alvarez splashed into the choppy waters of the Gulf of Tonkin. He successfully extracted himself from his parachute but discovered that he was coated with a black dye; the vial of shark repellent in his survival vest had broken. As militiamen approached in sampans, Alvarez's thoughts shifted to his wife of seven months, Tangee, and his beloved mother, Chloe. He then realized that he had forgotten to remove his wedding ring; pilots had been warned that captors could use information about family members to exploit prisoners during interrogations. Alvarez worked quickly to slip off the ring, and as the symbol of love floated to the bottom of the gulf, the young pilot made a promise to his bride: “Don't worry, sweetheart…someday I'll get you another one.” The vow was not necessary. Tangee divorced her prisoner husband nearly two years before his release from North Vietnam.4

Everett Alvarez was the first American serviceman captured in North Vietnam, and his more than eight and a half years in captivity would earn him the sobriquet the Old Man of the North. His chronological counterpart in the South was Army Captain Floyd “Jim” Thompson, whose nine years in captivity marked him as the Old Man of the South, and more grimly, the longest-held serviceman in American military history.5 Among those to follow Alvarez and Thompson in captivity were some men who were born to wave the flag, including an admiral's legacy, and they would be asked to sacrifice a great deal for their country. Years of torture, torment, frustration, and lack of freedom meant that there would be no fortunate sons in North Vietnam. One of those unfortunate sons was Bill Robinson.

Life in a Cotton-Mill Town

The small cotton-mill town of Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, was home to the Robinson clan. William Eugene (Gene) Robinson, Bill's grandfather, planted roots there in 1920, when, at the age of sixteen, he moved from southeastern Virginia to the tight-knit community in northeastern North Carolina. Gene Robinson was not alone. Between 1910 and 1920 the population of Roanoke Rapids more than doubled, from 1,670 to 3,369, as southerners throughout the region left the life of sharecropping and subsistence farming and moved to the cities in pursuit of the New South dream.6 The boosters of the New South hoped, as most articulately expressed by Henry Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, to build a “new economic and social order based on industry and scientific agriculture.” For Roanoke Rapids, and much of the region, the promise of a New South seemed to rest on textile manufacturing.7 In reality, “Roanoke Rapids did not exist before its mills,” suggests the journalist and historian Mimi Conway. “From its beginnings, the history of the town has been the history of the mills, a history of power struggles.” By 1910 several family-owned mills had been built in Roanoke Rapids, including the Rosemary Manufacturing Company, which “produced one third of all the damask tablecloths in the nation.”8

Although Gene Robinson had traveled only ten miles from southeastern Virginia to Roanoke Rapids, he in actuality had entered a new world of economic opportunity and a class system based on noblesse oblige. The paternalistic ethos of the family-owned mills manifested itself in a variety of forms: affordable and comfortable housing, community gardens maintained at company expense, canning facilities constructed by the company, as well as recreation centers, a hospital, and a library. Mill work did not offer an easy living, but by the sweat of his brow, Robinson forged a successful life. He married Geneva Cox in 1920 and they soon started a family. For Geneva, who had been raised in an orphanage, the only family that she ever truly knew was the one she raised with her husband. Their first child, William Jackson Robinson, the father of Bill Robinson, was born in 1922. Their second son, Harold, was born in 1924, and their only daughter, Hazel, was born in 1928. By almost any cultural or economic measure, the family of Gene and Geneva Robinson was a typical cotton-mill family. They worked hard, went to church, and raised their family.9

When all of the family-owned mills in Roanoke Rapids sold out in 1928 to the Simmons Company, a mattress manufacturer, the prevailing attitude of paternalism did not change. In 1956, however, when the J. P. Stevens Company, one of the largest and most aggressively anti-union textile firms doing business in the South, purchased the mills, it wasted little time in dismantling the vestiges of the former social contract between the workers and the mill owners. It sold the company-owned homes and recreation center and withdrew its support from the hospital. As Mimi Conway explains, “With the old system gone, many families…were left to shuttle between the memories of the old paternalistic way of life and the jarring reality of the new, corporate mode.”10 Not only did the era of noblesse oblige end in Roanoke Rapids with the J. P. Stevens takeover, but the textile conglomerate introduced a management strategy that had a devastating effect on the community, including the Robinson family. During his thirty-plus years in the mills, Gene Robinson had risen from the lowly position of floor worker to that of shift supervisor. But when the Stevens company inserted “college-educated people” into management and supervisory positions, Robinson found himself “doing at fifty-eight years old what he previously did at sixteen years old.” Despite the demotion and cut in pay, Robinson was among the fortunate survivors, as J. P. Stevens slashed its payroll by eliminating thousands of jobs. Nevertheless, he decided that he had had enough of mill life. “Always prepared for a rainy day,” Robinson used his savings to purchase a little grocery store, where he spent his remaining days “trying to help himself as well as others.” He had survived the Great Depression raising rabbits and vegetables and sharing with and feeding those in the neighborhood, and he would overcome this newest challenge.11

By this time Gene and Geneva's children had all married and started lives of their own. In 1940 their son William met Lillian Coppage, and they married on Christmas Day of that year. In a span of a little more than fifteen months they had two children; the first child, a daughter named Jacqueline, was born 14 May 1942, and Bill Robinson was born 28 August 1943. Many members of the Robinson family considered Bill “a miracle baby.” He had been a breech baby, “or what they referred to as a blue baby” in those days, and family members considered him “lucky to survive just to get here on earth.” During his childhood Bill also survived several brushes with death. When he was a youngster, the Robinsons often visited family in nearby Virginia Beach, Virginia, and on one occasion Bill “actually drowned” but was revived by a quick-thinking uncle who performed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. He then went through a period during which he was “a bleeder.” His mother worried that even a minor cut might produce massive hemorrhaging, so she prevented young Bill from walking barefoot and carefully monitored his activities. His closest encounter with death came as a result of complications from a tonsillectomy. Robinson's heart stopped beating during the operation and the doctors informed the family that the boy “was dead and there was nothing that they could do.” After he was revived, Robinson remained in the hospital for seventeen days, and the doctor believed that it was a miracle that he survived.12

Religion and family defined Bill's formative years. Lillian Robinson raised her children in the Methodist tradition, but other members of the Robinson clan were Baptist, and, ultimately, Bill remembers, “it didn't matter where we went to Sunday School, as long as we went to Sunday School.” His mother eventually joined the Union Mission in Roanoke Rapids, an independent nondenominational church that held services four times a week and conducted a number of children's programs. Lillian taught Sunday School and helped organize the annual Easter egg hunt and Christmas parade. She supervised the “Clothes Closet,” which accepted donated new and used clothing and distributed items free of charge to needy families. On Saturdays Lillian and another Union Mission member canvassed the neighborhoods and downtown areas for donations. Bill had a close relationship with his older sister, whom everyone called Jackie, and Ginger, the youngest of the family, who was born 24 June 1945. Ginger inherited her mother's temperament, and the two were nearly inseparable, to the point that Ginger followed “like a puppy dog” in her mother's footsteps. Ginger's older siblings regularly picked on her, the baby of the family. At times Jackie played the role of big brother; she was Bill's sparring partner. Their mother had a unique technique for settling disputes between the two. “She wouldn't take it out on us,” Bill recalled. “She would give us the switch and would make us take it out on each other. She became the referee, and that took a lot of the fun out of it.” The process certainly affected their characters, especially Jackie's: “She was the tough one of the family; she would take on anything and anybody at anytime.” Toughness was something the children needed because their father was rarely around to either nurture them or provide for them. In many ways and on numerous occasions, William's actions caused considerable heartache among the Robinson children, especially Bill.13

A Son in Search of a Father

William Robinson just had “a wild streak that existed in him,” and apparently “married life or the responsibility of a family was not part of his makings.” Trouble appeared on the horizon shortly before the end of World War II, when Robinson was drafted into the Army. He completed basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and was assigned to a military police unit. He never deployed overseas and in fact was released from the Army following the birth of his third child, Ginger. At the time the U.S. Army draft policy conscripted fathers who had two children but exempted those with three; thus, Robinson served about six months before returning home. His stay was brief. He rejoined the Army and accepted a three-year assignment in Panama. He left the Army in 1949 and returned to Roanoke Rapids. His presence confused Ginger, who had no real awareness that he was her father, and with a child's innocence asked her mother if she “was going to sleep with that man.” The romance of reunion did not last long, and William began to drift away from Lillian. Although they never legally separated or divorced, William left his family, forcing his wife to raise their children in a single-parent home. He would drop by from time to time, and on those occasions he sometimes seemed intent on reminding everyone why he left. The mere presence of young children seemed to cause him considerable annoyance; he could be heard complaining, “Damn children underneath your feet anywhere you go.” If William had simply left without ever returning, he might have actually caused less pain. But he did not. He reappeared on special occasions and on holidays, often attempting to win approval by giving gifts. One Christmas William came back to Roanoke Rapids and brought gifts for his entire family, including his children, his brother and sister, and his parents, but he did not bring his wife anything. He claimed that he had bought her some dishes but he had forgotten to pick them up. Lillian never received the set of dishes.14

Lillian Robinson was no stranger to hardship or familial burden. She was one of thirteen children. While Lillian was in high school, her mother suffered a stroke and was paralyzed on one side. Lillian became her mother's caregiver and also raised three of her younger siblings in her parents' house. Her father worked as an overseer at a lumberyard, and, although he died in 1945, his wife, Lillian's mother, retained lifetime rights to the house. Here in the house on Henry Street, Bill lived with his mother, two siblings and invalid grandmother while his father was stationed in Panama and for a short while after his return in 1949. Life here could be hectic. Lillian's sisters had their own versions of marital discord, divorced their husbands, and intermittently dropped their kids off at the house on Henry Street, so that for a time a couple of cousins grew up with Bill and his siblings.15

Lillian Robinson then moved her family into a series of old shotgun houses. The rent at the first place was five dollars per week, a second place cost seven dollars per week, or “a dollar a day for a house.” Financial uncertainty weighed heavily on the mother of three. She rarely knew where she would find the money to support her family. As a young child, Bill witnessed the mounting strain on his mother. His grandfather came by their house each Wednesday to take his mother grocery shopping, which meant that Tuesday nights were “either a glorious night or a night of tears. It was a good night if mother [had] received something in the mail from dad and she was able to buy our own groceries [the next day] rather than having to depend on granddaddy.” But there would be “teardrops all night long” if Lillian did not receive financial assistance from her husband: William's disregard for their welfare left Lillian no choice but to ask her father-in-law “for money to buy groceries to feed her children.” Throughout this ordeal of callous neglect, Lillian “scraped by the best she could, working with a friend of hers who owned a little grocery store.” Whatever the circumstances, she taught her children to be proud and to accept responsibility at a young age, advising them, “You might not have much, but you can be clean.” Even in the face of these difficult times, the children knew they could depend on their mother and “trust her guidance and leadership.” Still, young Bill suffered from the emotional strain caused by his father's actions, and little Ginger “sensed that things were not as they should be.”16

Sometime in 1952 or 1953 William Robinson succumbed to a woman “who promised him the world.” They worked and traveled in North Carolina, Tennessee, and South Carolina for Olin Mills Photography. He still returned to Roanoke Rapids periodically, but the visits were rife with deception. To his children he claimed that he too had fallen into “dire straits.” He lied. And what “hurt” Bill the “most” was that when his father visited he parked his car three blocks away, telling everyone that he had walked to see them because he had no way to get around; he actually had driven a brand-new automobile, a 1953 Oldsmobile, to town. Years later, Bill learned that the other woman had given his father thirty-five dollars a week—conscience money—to help Lillian and her children. William routinely kept the money for himself, however, forsaking his family and transferring the care of and responsibility for his children to his own father. The contrast in character between Gene Robinson and William was not lost on Bill, who lived by the creed, “If I was half the man my grandfather was then I would be twice the man that my daddy was.” Indeed, when Bill was in the fifth grade, his mother and his siblings moved in with Gene and Geneva. Soon Grandmother Coppage followed them. The new residence certainly pleased Bill: “This was the first time that we had actually had a toilet; up to that point we had an outhouse behind the house, but it was neat to have [a modern bathroom]. We ended up getting a hot water heater and a refrigerator. We thought we had died and gone to heaven. We had a washing machine and life was just getting good.”17

Life without a Mother

The material improvements certainly made life better for Bill and his sisters, but the late 1950s also brought an unimaginable loss. His Grandmother Coppage died in 1956. Then, in May 1958, his mother became ill. At first Lillian experienced severe headaches and the doctor prescribed a week of bed rest, which prevented her from collecting donations for the Union Mission. A determined soul, she resumed her fund-raising efforts the following Saturday, but her health was not improving. On Wednesday night, 11 June 1958, while sitting at the kitchen table, she began to hemorrhage. Gene had already reported to work, but the children were able to contact him, and he returned home while a neighbor came to help prepare Lillian for the trip to the hospital. She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. By Sunday Lillian was on her way to the Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. Gene had a sister in Durham who agreed to care for Lillian at her home if the treatments made her too sick to return to Roanoke Rapids, which they did.18

Ultimately the disease was so advanced that the doctors declared Lillian terminally ill and made the arrangements to—in effect—send her home to die. The hemorrhaging persisted and Lillian was in and out of the local hospital. At times the pain was so great that she was brought to tears, and she remained weak in body and confined to her bed. Her faith in God remained steadfast, however, and she calmly embraced the biblical axiom “His will not my will be done” throughout the crisis. As the family cared for Lillian, her husband stopped by now and then to check on her but made no special efforts to help his dying wife. William's thirty-sixth birthday was on 5 November 1958. He telephoned Ginger to let her know that he was coming home to visit and he wanted his mother to cook him a pot of navy beans to celebrate the occasion. When Ginger relayed the information to her grandmother, her mother overheard the conversation and she began to weep uncontrollably. After Lillian gained her composure, family members asked why she had broken down, and she told them that she was upset because she was too sick to bake her husband a birthday cake. The day after William's birthday, Lillian returned to the hospital. On 7 November 1958, after a nearly five-month battle with cancer, Lillian slipped into a coma and passed away around three o'clock in the afternoon.19

Even in these tragic circumstances, William refused to take on the responsibility of raising his son. Shortly before her mother's illness, Jackie, Bill's older sister, married, and his younger sister, Ginger, “married at a very young age.” This left Bill alone to be raised by his grandparents. Through all the disappointment, the betrayal, the abandonment, and the grievous loss of his mother, Bill not only survive...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Maps

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Unfortunate Sons

- 2. Separate Paths to Hell

- 3. After Ho

- 4. Coming Home

- 5. Forget and Move On

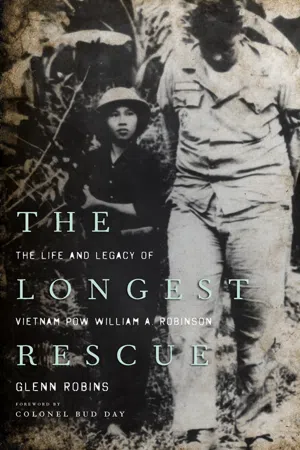

- 6. An Iconic Image

- 7. Legacies

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Suggested Readings

- Index