eBook - ePub

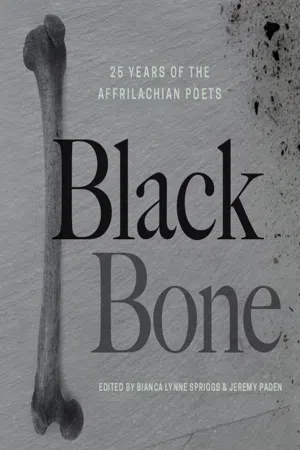

Black Bone

25 Years of the Affrilachian Poets

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Black Bone

25 Years of the Affrilachian Poets

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Black Bone by Bianca Lynne Spriggs, Jeremy Paden, Bianca Lynne Spriggs,Jeremy Paden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & North American Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Root

PAUL C. TAYLOR

Call Me Out My Name: Inventing Affrilachia

1.

I am grateful for, and humbled by, the opportunity to participate in this symposium on Affrilachia,1 for reasons both personal and professional. The personal reasons derive from facts like these: I was born and raised in Chattanooga, Tennessee; I spent two years teaching in Lexington, Kentucky, learning from the Affrilachian Poets that my roots in and routes through Appalachia might mean something worth reflecting on; and I come to you now from Centre County, Pennsylvania, in the upper reaches of the region. Like many of the other symposium participants, I am a living testament to the remarkable diversity, racial and otherwise, of Appalachia. Realizing this has been one of the important developments in my life, and I am glad to be in a position to say this publicly.

The professional reasons for my gratitude derive from facts like these: I am working on a book on Black Aesthetics, which means that I get paid to think about things like Affrilachian Poets, and about the conditions that call them into being, and about what they mean and do once they come into being. It is one thing, though, to think about black aesthetics, and another thing entirely to think about the concept at the heart of a particular venture in black aesthetics, while in the presence of the people who inaugurated and sustained the venture. My aim here is to do the second thing, albeit briefly: to think through the meaning of Affrilachia from the perspective of black aesthetics, and to do so in the home and in the presence of the Affrilachian Poets. Perhaps specifying the context in this way will clarify my feelings of gratitude and humility.

2.

We have Frank X Walker to thank for the word ‘Affrilachia’, and for his tireless work in support of the ideas and commitments that the word carries in its train. Walker’s journal, pluck!, declares the most central of these commitments quite clearly in its mission statement. The journal aims, it says, at “making the invisible visible,” which is to say, at showing that Appalachia is more than the lily-white, seamlessly rural home of Lil’ Abner and Jed Clampett.

This common picture of Appalachia is already too simple, even before we reach the question of blackness. It obscures, among other things, the complexities that attend the various modes of racialization into whiteness. (I don’t have space here to explore this thought any further, so I’ll just point to the remarkable television series “Justified,” currently running on FX, and move on.) But the standard image of Appalachia probably works hardest at obscuring the presence, plurality, and perspectives of black folks in the region. This is what pluck! aims most assiduously to contest.

Putting the concern that animates pluck! in terms of invisibility will put most people immediately in mind of Ralph Ellison, whose Invisible Man established the problematic of black invisibility in the forms that most of us know best. To be invisible in this sense is a matter not of physics or physiology, of bent light waves or of impaired optical faculties. It is a matter of psychology and morals: it is a matter of what philosophers call recognition, of being regarded as a person, as someone with a moral status and a point of view: someone whose presence makes a difference worth attending to.

The rhetoric of invisibility has served well in this capacity for a long time, appearing before Ellison in the work of Du Bois and others, and well afterwards in, for example, the work of Michele Wallace. (There may, in fact, be no better précis of the dialectic of recognition than Du Bois’s discussion of ‘seeing oneself through the eyes of others’ in his account of double-consciousness.) But focusing on the philosophical problematic behind the ocular metaphors points beyond the metaphor, and invites us to consider other sensory and experiential registers.

When Ellison’s narrator bumps into the uncomprehending—the vehemently uncomprehending—white man, he says that the man called him ‘an insulting name.’ It’s not hard to imagine what that name was, especially if one has read Fanon. (“Look, a Negro! Or, more simply: Dirty nigger!”) And once we imagine this, it is easy to see that the depersonalization and sub-personalization that constitute invisibility go hand in hand with denying the individuality that we signify with names and titles. (Not ‘Excuse me, sir,’ but ‘Dirty nigger!’)

This link between invisibility, recognition, and naming is what makes Sidney Poitier say, ‘Call me ‘Mr. Tibbs.’ It helped motivate the famous signs from the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, the ones that, as the great contemporary artist Glenn Ligon reminds us, read, ‘I AM A MAN.’ It drove my mother to insist, in the early seventies (back when they still talked this way), that white salesclerks call her ‘Mrs. Taylor’ rather than ‘honey’ or ‘dear.’ To insist in these ways on just these modes of address is to say that there is a name for what I am, for the kind of thing, the kind of creature, the kind of being, that I am. It is to say further that I will insist on this name, and demand that you resist your impulse to call me otherwise. I am not a boy, or a beast of burden, or a piece of property, or the object of your condescendingly feigned and double-edged familiarity. I have a name that accurately and appropriately identifies me, and insisting on it is my prerogative and duty in a properly arranged scheme of social relationships.

The invention of the term ‘Affrilachia’ must, it seems to me, be seen in this context. Invisibility, with its links to naming and recognition, is one of the central tropes in the black aesthetic tradition, as I understand it. It is just one of the central tropes, of course, alongside reflections on beauty and the black body (think of Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, or of there being no Black Miss Americas until—forgive the expression—high-yellow Vanessa Williams), on authenticity (think of Jean Toomer, or of Dave Chappelle making fun of Wayne Brady, and of Wayne Brady joining him), on the role of politics in art (think of Du Bois and Locke arguing about propaganda, and of Maulana Karenga wondering what in the world there was to argue about), and on the meaning of style (think of flashy white basketball players nicknamed ‘white chocolate,’ and of what people once called ‘blue eyed soul’ but now call ‘Robin Thicke’). Nevertheless, invisibility may be the most prominent trope, not least because Ellison’s novel quickly became and, as far as I know, remains...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Copyright

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Root

- Limb

- Tongue

- Bios

- Reprint Credits