- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

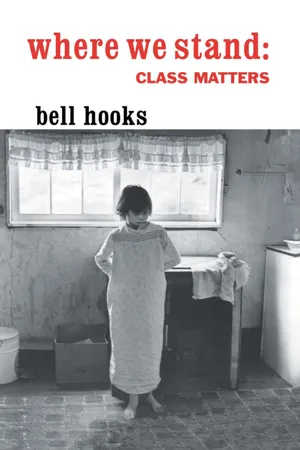

About this book

Drawing on both her roots in Kentucky and her adventures with Manhattan Coop boards, Where We Stand is a successful black woman's reflection--personal, straight forward, and rigorously honest--on how our dilemmas of class and race are intertwined, and how we can find ways to think beyond them.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Making the Personal

Political: Class in

the Family

Living with many bodies in a small space, one is raised with notions of property and privacy quite different from those of people who have always had room. In our house, rooms were shared. Our first house, a rental home, had three bedrooms. It was a concrete block house that had been built as a dwelling for working men who came briefly to this secluded site to search the ground for oil. There were few windows. Dark and cool like a cave, it was a house without memory or history. We did not leave our imprint there. The concrete was too solid to be moved by the details of a couple with three small children and more on the way, trying to create their first home. Situated at the top of a small hill, this house was surrounded by thickets of greenery with wild honeysuckle and blackberry bushes growing everywhere. Behind these thickets rows and rows of crops spread out like blankets. Their stillness and beauty stood out in contrast to the leveled nature surrounding the concrete house—mowed-down grass full of bits and pieces of cement.

Loneliness and fear surrounded this house. A fortress instead of a shelter, it was the perfect place for a new husband, a new father, to build his own patriarchal empire in the home—solid, complete, cold. Architecturally, this house stands out in my memory because of the coolness of the concrete floors. So cold they often made one pull naked feet back under cover, recoiling, like when flesh touches something hot and swiftly pulls away. In a liminal space between the living room and kitchen where a dining room might have been, bunk beds for children were placed. And the children had to learn how to be careful. Falling out of bed could crack one’s head wide open, could knock one out cold, leaving flesh as cold as concrete floors. I fell once. That’s my imprint: the memory that will not let me forget this house even though we did not live there long.

It lacked too much. There was no bathtub. Water had to be heated, carried, and poured into huge tin tubs. Bathing took place in the kitchen to make this ritual of boiling and pouring and washing take less time. There was no such thing as privacy. Water was scarce, precious, to be used sparingly, and never wasted. Or so the grown-ups told us. This was a better story than the hidden fact that water costs, that too many children running water meant more money to pay. As small children we never thought of cost, of water as a resource. Primitive ecology made us think of it always as magical. It was always precious—to be appreciated and treated with care. We longed to be naked in summer, splashing in plastic pools or playing with hoses, but we knew better. We knew that to leave faucets running was to waste. Water was not to be wasted.

It was a house of concrete blocks put together with stone and cement, a cool house in summer, a cold house in winter— already a harsh landscape. We tried to give this house memories, but it refused to contain them. Impenetrable, the concrete would not hold our stories. Ultimately, we left this house, more bleak and forlorn than before we lived there—a house that would soon be torn down to make way for new housing projects.

There was always a lack of money in our house. As small children we did not know this. Mama was a young fifties mom, her notions of motherhood shaped by magazines and television commercials. Children, she had learned, should not be privy to grown-up concerns, especially grown-up worries. Husband and wife did not discuss or argue in front of children. They waited until children were asleep and talked in their marital bed, voices low, hushed, full of hidden secrets.

I do not know if our mother ever thought of herself as poor or working class. She had come to marriage with our father as a teenage divorcée with two girl children. In those years they lived with their biological father. On weekends they visited with us. Daddy had probably married her because she was pregnant. He was a longtime bachelor, an only child, a mama’s boy who could have stayed home forever and used it as the secure site from which to roam and play and be a boy forever. Instead he was trapped by the lures and longings of a beautiful eager young woman more than ten years his junior. He had wanted her even if he had not been sure he wanted to be tied down—unable to roam.

Mama, like her gorgeous sisters and the handsome man she married, loved fun and freedom. She liked to roam. But she also liked playing house. And the concrete box was for her the fulfillment of deep-seated longings. She had finally truly left her mother’s house. There would be no going back—no return, no tears, no regret. She was in her second marriage to stay. It was to be the site of her redemption—the second chance on love that would let her dreams be born again. Only mama loved the start of a new life in the concrete box, away from the eyes of a questioning world. Even if the solitude of so much surrounding wilderness threatened, she was secure in the knowledge that she would protect her home—her world—by any means necessary. She was stranded there, on top of a hill, at home with the children. Our daddy, a working man, left early and came home late. His roaming had not ceased. It had merely adjusted itself to the fact of wife and children. Mama, who did not drive, who had no neighbors to chat with, no money to spend, was the wild roaming one who would soon be domesticated—her spirit tamed and broken.

Being poor and working class was never a topic in the concrete box. We were too young to understand class, to share our mother’s dreams of moving up and away from the house and family of her origins. A girl without proper education, without the right background, could only change her status through marriage. As a wife she was entitled to respect. All her dreams were about changing her material status, about entering a world where she would have all the trappings of having made it—of having escaped “over home” the tyranny of her mother’s house and her mother’s ways. In the world’s eyes, the folks in that house with their old ways who lived without social security cards, who preferred radio to television, were poor.

Even as small children we knew our father was not pleased with his mother-in-law. He felt she dominated her husband and had taught her daughters that it was fine to do the same thing with the men in their lives. Before marrying he let mama know who would be wearing the pants in his house. It would always be his house.

The house mama was coming from was a rambling two-story wood frame shack with rooms added on according to the temperament of Baba, mama’s mother. Already old when we were born, she lived in the house with her husband, our beloved grandfather Daddy Gus. He was everything she was not. A God-fearing, quiet man who followed orders, who never raised his voice or his hand, he was our family saint. Baba was the beloved devil, the fallen angel. Her word was law—a sharp tongue, a quick temper, and the ruthless wit and will needed to make everything go her way.

Unlike the concrete box, the house mama grew up in at 1200 Broad Street was the embodiment of the enchantment of memory. Change was neither needed nor wanted. The old ways of living and being in the world that had lasted were the only ways worth holding onto and sacrificing for. At Baba’s house everything that could be made from scratch and not bought in a store was of greater value. It was a house where self-sufficiency was the order of the day. The earth was there for the growing of vegetables and flowers and for the breeding of fishing worms. Little illegal sheds in the back housed chickens for laying fresh eggs. Homegrown grapes grew for making wine, and fruit trees for jam. Butter was churned in this house. Soap was made, odd-shaped chunks made with lye. And cigarettes were rolled with tobacco that had been grown, picked, cured, and made ready for smoking and for twisting and braiding into wreaths by the family, to serve as protection against moths.

This was a house where nothing was ever thrown away and everything had a use. Crowded with objects and memories, there was no way for a child to know that it was the home of grownups without social security numbers and regular jobs. Everybody there was always busy. Idleness and self-sufficiency did not go together. All the rooms in this house were crowded with memories; every object had a story to be told by mouths that had lived in the world a long time, mouths that remembered.

Baba’s wrath could be incurred by small things, a child touching objects without permission, wanting anything before it was offered by a grown-up. In this house everything was ritual, even the manner of greeting. There was no modern casualness. All rites of remem-brance had to be conducted with awareness and respect. One’s elders spoke first. A child listened but said nothing. A child waited to be given permission to speak. And whenever a child was out of their place, punishment was required to teach the lesson.

Going to visit or stay at this house was an adventure. There was much to see and do but there was also much that could go wrong. This was the house where everyone lived against the grain. They created their own rules, their own forms of rough justice. It was an unconventional house. That was as true of the architectural plan as it was of the daily habits of its inhabitants. When I was a girl, four people lived in this house of many rooms—Baba and Daddy Gus, Aunt Margaret (mama’s unmarried and childless sister), and Bo (the boy child of a daughter who had died). Everybody had a room of their own—a room reflecting the distinctiveness of their character and their being.

Bo’s space was a new addition at the back of the house, small and private. Baba’s room was a huge space at the center of the house. It contained her intimate treasures. There was no exploring in this room; it was off limits to anyone save its owner. Then there was the tiny room of Daddy Gus with a small single bed. This was a room full of found treasures—a room with a mattress where one could lie there and look out the window, which went from ceiling to floor. This room was open to the public, and children were the eager public waiting to see what new objects our granddaddy had added to his store of lost and found objects. Upstairs Aunt Margaret lived in a room with sloping ceilings. Her bed was soft, a mound of feather mattresses stacked on top of one another. From girlhood to womanhood all her treasures lay recklessly tossed about. The bed was rarely made. She liked mess—having everything where it could be seen, a half-filled glass, a half-read letter, a book that had been turned to the same page for more than ten years.

Over home at Baba’s house I learned old things were always better than anything new. Found objects were everywhere. Some were useful, others purely decorative. Every object had a story. Nothing enchanted me more than to hear the history of each everyday object—how it arrived at this particular place. A quiltmaker, Baba was at her best sharing the story of cloth, a quilt made from the cotton dresses of my mother and her sisters, a quilt made from Daddy Gus’s suits. A dress first seen in an old photo then the real thing pulled magically out of a trunk somewhere. The object was looked and talked about in two ways—from two perspectives.

Baba did not read or write. Telling a story, listening to a story being told is where knowledge was for her. Conversation is not a place of meaningless chitchat. It is the place where everything must be learned—the site of all epistemology. Over home, everyone is always talking, explaining, illustrating and telling stories with care and excitement. Over home, children can listen to grown-up stories as long as they do not speak. We learn early that there is no place for us in grown-up conversations.

More than any grown-up, Baba taught me about aesthetics, how to really look at things, how to find the inherent beauty. This was a rule in that house; everything, every object, has an element of beauty. Looking deep one sees the beauty and hears the story. Daddy Gus told me that all objects speak. When we really look we can hear the object speak. They believe home is a place where one is enclosed in endless stories. Like arms, they hold and embrace memory. We are only alive in memory. To remember together is the highest form of communion.

Communion with life begins with the earth, and these people, my kin, are people of the earth. They grow things to live. In the front yard herbs and flowers. Delphiniums, tulips, marigolds—all these words I cannot keep inside my head. A swirl of color seized my senses as I walked the stretch of the garden with Baba, as she pushed me in the swing—a swing made with huge braided rope and a board hanging from the tallest tree. There was a story there, about the climbing of the tree, the hanging of the rope, of the possibility of falling.

In the backyard vegetables grew. Scarecrows hung to chase away birds who could clear a field of every crop. My task was to learn how to walk the rows without stepping on growing things. Life was everywhere, under my feet and over my head. The lure of life was everywhere in everything. The first time I dug a fishing worm and watched it move in my hand, feeling the sensual grittiness of mingled dirt and wet, I knew that there is life below and above—always life—that it lures and intoxicates. The chickens laying eggs were such a mystery. We laughed at the way they sat. We laughed at the sounds they made. And we relished being chosen to gather eggs. One must have tender hands to hold eggs, tender words to soothe chickens as they roost.

Everyone in our world talked about race and nobody talked about class. Even though we knew that mama spent her teenage years wanting to run away from this backwoods house and old ways, to have new things, store-bought things, no one talked about class. No one talked about the fact that no one had “real” jobs at 1200 Broad Street, that no one made real money. No one called their lifestyle “alternative” or Utopian. Even though it was the 1960s, no one called them hippies. It was just this world where the old ways remained supreme. It was the world of the premodern, the world of poor agrarian southern black landowners living under a regime of racial apartheid. In Baba’s world she made the rules, uncaring about what the outside world thought about race or class, or being poor. The first rule of the backwoods is that everybody must think for themselves and listen to what’s inside them and follow. That’s the reason we have God, Baba used to say. God is above the law.

Living in a world above the absolutes of law and man-made convention was what any black person in their right mind needed to do if they wanted to keep a hold on life. Letting white folks or anybody else control your mind and your body, too, was a surefire way to fail in this life. That’s what Baba used to say—may as well kill yourself and be done with it. As a girl I wanted more than anything to live in this world of the old ways. Instead I had to live with mama and the world of the new. Inside me I felt brokenhearted and torn apart. I was an old soul, and the world of the new could never claim me.

I was far away from home before I realized that my smart, work-hard-as-a-janitor-at-the-post-office daddy (who had been in the “colored infantry,” fought in wars, and traveled the world) had nothing but stone-cold, hard contempt for these non-reading black folks who lived above the law. A patriotic patriarch, he lived within the law and was proud of it. To mama he openly expressed his contempt of the world she had come from, intensifying her class shame and her longing to move as far away from the old ways as she could without severing all ties. She was always on guard to break the connection if any of her children were getting the idea that they could live on the edge as her parents did, flouting every convention. Lacking the inner strength to live within the old ways, mama needed convention to feel secure. And it was clear to everybody except the inhabitants of the house on Broad Street that the old ways would soon be forgotten. To survive she had to make her peace with the world of the modern and the new. Turning her back on the old ways, she opened her heart and soul to the cheaply made world of the store-bought.

Determined to move on up, mama moved us from the country into the city, out of the concrete box into Mr. Porter’s house. Now that was a house with history and memory. He had lived to be an old, old man in this house and had died there, his house kept just the way it was when he first moved in, with only the bathroom added on. To mama this house was paradise. A formal dining room, a guest room, a service porch, a big kitchen, a master bedroom downstairs, and two big rooms for the children upstairs. Uninsulated, attic-like rooms had short, sloped ceilings and windows that went from wall to floor. They were cold in winter, impossible to heat. None of that mattered to mama. She was moving into a freshly painted big white house with a lovely front porch.

Built in the early 1900s, Mr. Porter’s house was full of possibilities—a house one could dream in. It was never clear what our father thought about this house or the move. No matter where we lived, it would always be his house. His wife and children would always live there because he allowed them to do so. This much was clear. He worked on the house because it was a man’s job to do home improvement. We watched in awe as he walled in the side porch, expanding and making a little room that would be my brother’s room as well as a storage place.

Like all old houses of this period, there were few closets. There were crawl spaces where stuff could be stored. Closets were not needed in a world where folks possessed the clothes on their backs and a few more items. Now that everyone bought more, bureaus and armoires were needed so that clothing could be stored properly. We had chests of drawers for everyone.

We lived with Mr. Porter’s ghosts and his memories in this two-story house with its one added-on bedroom. By then we were a family of six girls, one boy, mama and papa. Away from the lonely house on the hill we had to learn to live with neighbors with watching eyes and whispering tongues. Mama was determined that there should be nothing said against her or her children. We had moved on up into a neighborhood of retired teachers and elderly women and men. We had to learn to behave accordingly.

Still no one talked about class. Mama expressed her appreciation for nice things, her pleasure in her new home, but she did not voice her delight at leaving the old ways behind. Backwoods folks who lived recklessly above the law were not respectable citizens. Seen as crazy and strange, theirs was an outlaw culture—a culture without the tidy rules of middle-class mannerisms, a culture on the edge. Mama refused to live her life on the edge.

In Mr. Porter’s house we all became more aware of money. Problems with money, having enough to do what was needed and what was desired, were still never talked about in relation to class. More than anything, like most of the black folks in our neighborhood, we saw money problems as having to do with race, with the fact that white folks kept the good jobs— the well-paying jobs—for themselves. Even though our dad made a decent salary at his job, racial apartheid meant that he could never make the salary a white man made doing the same job. As a black man in the apartheid south he was lucky to have a job with a regular paycheck.

Being the man and making the money gave daddy the right to rule, to decide everything, to overthrow mama’s authority at any moment. More than anything else that he hated about married life our dad hated having to share his money. He doled small amounts of money out for household expenses and wanted everything to be accounted for. Determined that there should be no excess for luxury or waste, he made sure that he gave just barely enough to cover expenses. When it came to the material needs of growing children, he took almost everything to be a luxury—from schoolbooks to school clothes. Constantly, we heard the mantra that he had not needed any of these extras (money for band, for gym clothes) growing up. Mostly, he behaved as though these were not his problems.

Mama heard all our material longings. She listened to the pain of our lack. And it was she who tried to give us the desires of our hearts, all t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- contents

- preface

- introduction Class Matters

- 1 Making the Personal Political: Class in the Family

- 2 Coming to Class Consciousness

- 3 Class and the Politics of Living Simply

- 4 Money Hungry

- 5 The Politics of Greed

- 6 Being Rich

- 7 The Me-Me Class: The Young and the Ruthless

- 8 Class and Race: The New Black Elite

- 9 Feminism and Class Power

- 10 White Poverty: The Politics of Invisibility

- 11 Solidarity with the Poor

- 12 Class Claims: Real Estate Racism

- 13 Crossing Class Boundaries

- 14 Living without Class Hierarchy

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Where We Stand by bell hooks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.