![]()

1

THE HONDURAN LIBERAL REFORMS

AND THE RISE OF WEST INDIAN MIGRATION

The initial stages of the West Indian migration experience in Honduras are best understood within the context of the liberal reform period in Honduran historiography. Banana companies and economically minded Honduran liberals used the reforms to create an extralegal environment in which fruit corporations benefited economically from the political and social agendas of the nation. Because West Indians were an imported labor force hired specifically by the fruit companies, they remained in a quasilegal position that left them outside the scope of the state. This was clearly a benefit to the corporations that were able to control West Indian labor on the North Coast, but it proved to be a mixed blessing for the West Indians, whose fate in Honduras was often decided by others. Scholars in the United States and Honduras such as Darío Euraque, Héctor Pérez Brignoli, Mario Argueta, and Mario Posas have examined the complexities of the liberal reforms and their impact on the political, economic, social, and labor dimensions of the modern Honduran state.

This chapter focuses on the reforms as they relate to the emergence of the West Indian migrant population in Honduras and their settlement in the banana enclaves of the North Coast. By adhering to established analyses of this period, I do not seek to reinterpret the existing literature on the liberal reforms in Honduran historiography, but rather to provide the context for a better understanding of the political, economic, and social climate West Indians entered on their arrival.

The liberal reforms represent a major shift in the history of migration in Honduras. The fallout from the political and economic legislation during the period constitutes perhaps the most comprehensive example of population shift in the history of the modern state of Honduras. Among those arriving on the North Coast of Honduras were North American businessmen seeking to benefit from liberal economic policies in agriculture, Honduran elites shifting from coffee-producing regions to the easily accessible banana lands and commercial opportunities of the North Coast frontier, 1 European and Middle Eastern immigrants capitalizing on the expanding mercantilist economy as a result of the expansion of agribusiness, West Indians seeking employment as laborers and skilled workers, and Hondurans and other Central Americans fleeing from the interior to the North Coast in search of more viable means of making a living. All of these groups were seeking to share in the liberal vision of a Honduras deeply integrated into the global economy and the modernization and industrial processes.

Honduran historiography dates the beginning of the liberal reform period from 1876 with the inauguration of the Liberal party candidate Marco Aurelio Soto (1876–1883) as president of the republic. Kenneth Finney suggests that 1876 was a watershed year for Honduras owing to such innovative legislation as the suppression of the tithe, the introduction of public education, and the codification of legal commercial mining and the passage of administrative laws aimed at the promotion of economic development within the country. 2 Marvin Barahona maintains that, in order to allow access to agricultural lands, the reforms also called for the separation of church and state and the nationalization of church lands in an effort to curb the latifundia systems that monopolized land and inhibited the development of natural resources for the benefit of the nation. Furthermore, the system hindered the development of large-scale agricultural enterprises believed by liberals to be the catalyst for economic growth. 3

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the reforms as they relate to the emergence of the West Indian community in Honduras is their facilitation of new ties between Honduras and the world economy by offering incentives to both Hondurans and foreigners to develop and expand the export agricultural industry. 4 The reforms served as the catalyst that ignited the banana boom in Honduras by regenerating the Honduran agricultural industry and redirecting the economic orientation of the nation from the interior to the North Coast. 5 Darío Euraque asserts that Honduran efforts to establish banana plantations on the North Coast between 1870 and the first decades of the twentieth century represented an obstacle for the legislature in Tegucigalpa to develop other possibilities for agriculture. 6 The reforms established the North Coast of the country as the economic center of the nation and encouraged an influx of both human and economic capital into the region.

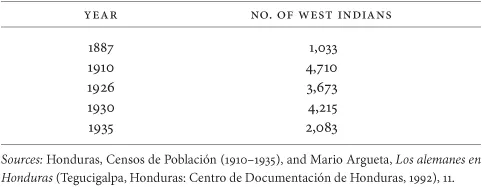

Hondurans from all parts of the country converged on the North Coast to take advantage of the numerous job opportunities and higher wages offered in the region. At the height of banana production, employment on the North Coast was ten to fifteen times higher than in the interior. 7 The prospect of lucrative wages that attracted Hondurans to the North Coast also attracted thousands of West Indians to the region. With its relative economic prosperity and long history of cultural and ethnic pluralism, the North Coast appeared to be an area where West Indians would thrive. Because the export banana industry was in its early stages in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some scholars have argued that West Indians were in prime position to monopolize the Honduran labor market due to their prior experience with banana production in their home islands and to the racial sensibilities of North American employers who relied on subordinate black labor. Hector Perez Brignoli highlights these sentiments in exposing views shared by many fruit company executives that blacks, particularly West Indians, were the only group predisposed to work in railroad and plantation construction in the extreme heat because of the affinity of African-descended peoples to warm climates. 8 Despite the racist notions of North Americans and some Hondurans, West Indians were never the majority population on the North Coast and constantly found themselves at odds with Hondurans over competition for employment. Table 1.1 lists the number of documented West Indians available through Honduran immigration and census records. However, these numbers may not represent all West Indians because many entered the country as temporary workers for the fruit companies, rather than as immigrants seeking resettlement in Honduras.

Justifiable demand for jobs on the part of Hondurans was often the root cause of anti–West Indian sentiment. While the economic agenda of the liberal reforms accounted for an influx of foreign capital and business ventures into Honduras, the reformers did not realize that their efforts toward modernization would translate into racial and ethnic tension with a foreign labor force. They did not foresee the vast importation of foreign labor into the country. West Indians and their descendants were never the intended beneficiaries of liberal policies. There was no reason for reformers to believe that fruit companies would not favor local Honduran labor. Such was the case in most instances. However, West Indians in the early days of the foreign-dominated industry did receive considerable advantages in terms of higher-quality and often higher-paying jobs, and a better overall quality of life that most Hondurans were not afforded. Mario Posas has documented extensively that most Hondurans were not granted such advancements in the banana zones without protest through strikes and other forms of collective resistance, a reality West Indians never experienced.

TABLE 1.1 Estimated number of Documented West Indians on the north Coast, 1887–1935

Many scholars of the West Indian diaspora in Latin America have mistakenly viewed the competition between West Indians and the local citizenry as only an economic or labor issue. Such an analysis does a disservice to the study of the Honduran situation in that labor and economic uncertainty quickly manifested into political pressures. The West Indian presence on the North Coast in many instances challenged the agenda of reformers. Although Marco Aurelio Soto is often credited with establishing the economic agenda of the Honduran liberal reforms, his strategy also had political implications. Soto, along with his cousin Ramón Rosa, instituted a political approach based largely on the latter’s efforts to unify the territory of Honduras politically and culturally. Rosa, in an effort to sustain the territorial integrity of Honduras and promote political stability, sought to unify the nation on political and constitutional models from North American and European democracies. 9 The establishment of public education, the debate over the national image of Honduras, and the liberal strategies of social development can all be traced back to the positivist-influenced thinking of Ramón Rosa. The economic approach of Marco Aurelio Soto, while credited for providing the policies that led to the influx of foreign capital into Honduras, surpassed the efforts of Rosa in terms of lasting impact. Some scholars have argued that both approaches did very little to change the fundamental structure of Honduran society. The economic and political visions of the country were changed, but the social and cultural structure based on a hierarchy established by the Creole elite from colonial times remained intact. 10

Reform did not promote the surge in modernization that reformers hoped. Honduras remained a weak state, and the revenues collected from the developing agricultural industry were rarely enough to strengthen the economic and political structure of the national government. 11 In no place was this more evident than on the North Coast. The enormous profits garnered by the fruit companies most often made their way back to New Orleans, Boston, New York, and other U.S. cities where the fruit companies were headquartered. Elizet Payne suggests that the inability of Liberals to create a strong centralized state in the region inadvertently indebted the nation to North American investors. 12 The government created new departments on the North Coast in an effort to politically consolidate the region under the umbrella of the state, but it did not have the infrastructure in place to enforce the laws. Countless examples throughout this study demonstrate disconnect between Tegucigalpa and the North Coast. Government representatives in the North Coast departments often held short tenures, and most mail and telegraph correspondence was irregular. This would pose serious challenges in immigration issues concerning West Indians, as most department officials were not competent interpreters of laws and procedures and handled issues such as deportation haphazardly. Because of an inadequate state presence in the region, the fruit companies were able to utilize this environment to their benefit and circumvent labor and immigration laws regarding hiring West Indians, a theme that is discussed further in subsequent chapters.

Prior to the institution of the liberal reforms, the Honduran economy was at subsistence level. Forestry and mining aided in sustaining the local economy and by 1855 accounted for two-thirds of the country’s exports. 13 However, these industries were mostly unregulated and failed to spark an export-oriented economy that would achieve larger financial gains for the nation. 14 In addition, industries such as forestry and the contraband trade were historically dominated by the British and other Europeans in contested regions such as La Mosquitia and the colony of British Honduras during the colonial period. Taylor Mack has demonstrated the role of Hondurans as smugglers in this enterprise and the far-reaching impact of the trade from Trujillo and La Mosquitia through established networks to Comayagua and Tegucigalpa. 15 The mining industry of Honduras in the regions around the capital city of Tegucigalpa had an enormous foreign presence in terms of investment capital.

The North American—specifically, the United States—presence in Honduras increased tremendously following the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty between Britain and the United States in 1850. 16 Kenneth Bourne maintains that the British entered into the treaty with the United States in the hope of securing free and equal use of a future interoceanic canal in the region. The British also hoped to present a formal barrier to the territorial expansion of the United States. 17 Unfortunately for the British, the treaty did neither. Honduras did not become the site of the canal, and disputes over British expansion in the region, stemming from debates over the Monroe Doctrine, eventually led to the loss of British territories in La Mosquitia and the Bay Islands.

The increased U.S. presence in Honduran political affairs set the stage for future intrusion into the Honduran economy. The political situation in the emerging nation fueled much of this. Honduras was unable to achieve economic success and promote large-scale development in line with the liberal reforms due to continued political instability within the country. In 1897, Albert Morlan, an independent American traveler to Honduras from Indianapolis, Indiana, wrote that many of the local fruit developers, in an effort to monopolize control over the local banana industry and maintain their contracts with New York– and New Orleans–based importers, often employed the local militia in order to intimidate the competition. 18 Such actions promoted a bellicose environment in which local business competition led to wide-scale armed conflict in certain regions. Writing in 1914, Frederick Upham Adams maintained that within a fifteen-year period, there had been six revolutions in Honduras. 19 In such a political climate, with constant in-fighting over control of the resource-rich mining and agricultural areas, unregulated exploitation of wealth by Honduran elites and their U.S. cohorts was common. Ironically, during the same period, Euraque notes that some thirty-seven lan...