![]()

1

Inertia, Suspension and Mobility in the Global City

Stephanie Hemelryk Donald and Christoph Lindner

Introduction

Inertia is a state of profound inaction. It describes a total lack of movement or willpower, a stillness that connotes death. This book deals, then, with a contradiction. It addresses visual practices relating to inertia in the global city. It does so in relation to a broad selection of urban settings and cultural contexts in Asia, Europe, North America and the Middle East. Cities discussed include Amsterdam, Berlin, Beirut, Lisbon, New York, Paris and Vienna. Chinese cities are in evidence too, as the sine qua non of the story of contemporary urban expansionism. This geographical spread is relevant for three reasons. First, it enables the book to address major cultural, economic and political centres which can be taken as representative of key developments in the rise and future of the global city. These include many subcategories of urban expansion: megacities of the global south, post-colonial hubs, cities of exclusion, exploding cities of Asia, world heritage cities and global financial capitals. Second, the range of cities enables the book to track artistic practices and urban conditions across diverse geographical and cultural contexts to see what is specific to individual cities and what ‘travels’ between cities and regions. Third, the emphasis on the city is also a focus on the people who inhabit them, those who, as Luis Buñuel would have it in his classic depiction of the emergent global city, Los Olvidados (1950), ‘live below the metropolis’. In short, we are trying to achieve a balance between urban theory and philosophical enquiry, and between visual analysis and cultural politics.

Inertia and Suspension

We have claimed that the central, organizing concern of this book is inertia, and yet we have to admit that the city is a mobile, urgent and active environment. Most people live in cities because they must, but also because they cannot imagine living anywhere else, and because that is where modern lives and cultures are increasingly shaped and pursued. The development of cities has been supported by the movements of peoples between countries, nations, continents and across time. They travel in search of resources, livelihoods and each other. The phenomenon of global cities is possible because of the human capacity to network across languages and cultures, to move physically or imaginatively, to make connections and to trade. Why then, would we write about inertia when it is so clear, and so forcibly demonstrated, that the city is always a lively place of movement and flow? Certainly, we could respond that there are some cases where liveliness is diminished, where the politics of the city veer away from trade and mutual energy and towards war and suspicion. The city becomes violent, bleak and repressive. Perhaps in these cases inertia is the response to pain. But we argue across this book that inertia is also the necessary corollary of mobility and energy in cities that are not suffering in such obvious ways.

We approach this topic by paying attention (in the full sense of the word) to the work of visual artists and filmmakers who incorporate stillness, suspension and indistinctness in their work, and we place these analyses in the context of social-political realities and aesthetic frameworks that render these practices legible as works acknowledging inertia as an ontological state that is integral, if in ways that are not always apparent, to everyday life.

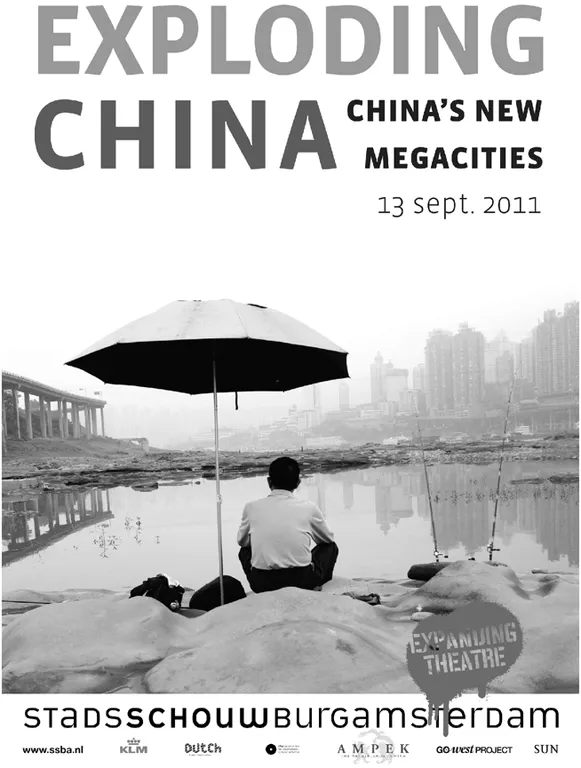

When an idea is held in common by more than one scholar, living on different sides of the world and working in and through different cultural lenses, the pathways along which they have travelled to a meeting point – that moment of alert thought from which to begin the discussion – are bound to be different. So, we open the deliberations of this book by reconvening these pathways to and from our convergent idea of inertia, and trace its connection to the city, which is our mutual object of research. Given our common interest in visual forms of communication and expression, it is unsurprising that these pathways commence with images that we have encountered, in our walks around the city, in the books on our office shelves and in the many other exhibitions and events into which we are drawn by the pathways of other thinkers, artists and filmmakers. However, it was co-location at the University of Amsterdam (Christoph Lindner as host and Stephanie Hemelryk Donald as visitor) that brought the idea to fruition. On the first day of Hemelryk’s arrival, Amsterdam’s Stadsschouwburg (City Theatre) presented a multimedia discussion of the new ‘exploding’ Chinese megacity (Figure 1.1). This was ironic for someone who had just flown in from the Asian region to spend time in a relatively small but historically saturated European city, specifically intending to think about how mobility and immobility manifest European cities and European structures of fear.

1.1 Exploding China poster (adapted from the cover of How the City Moved to Mr. Sun by Michiel Hulshof and Daan Roggeveen). The presentation at the Stadsschouwburg was energetic and informed. It featured journalists, Chinese and European scholars, comedians, musicians and, inevitably, an architect. The emphasis was, as the title indicates, on accelerated change, ruthless progress, massive destruction and construction, environmental degradation and over-development, evidenced by cities or city quarters that are built for quick investment profit but remain unoccupied. The term ‘ghost cities’ hung suspended in the air next to the driving paradigm of megacities that had, after all, drawn in the rapt metropolitan and multilingual audience. An almost entirely Dutch audience was comfortable in English, and Chinese worked for many too. The concept of inertia was not mentioned – or not so far as we recall – but in retrospect, the evening’s exuberant warning to Europe of its seeming galloping irrelevance in the face of China’s rise suggested not only a local paralysis, but also carried undertones of China’s points of inertia at the heart of its new megacities, and in the overspill into ghost cities that have never quite fulfilled their promise. The inertia that dared not speak its name is manifold in the Chinese condition. There are the displaced rural populations forcibly migrated from previous cultural environments, with no hope of returning to old homes that are now submerged by dam water, or covered in asphalt. There are the populations who live, like Buñuel’s urban underclass in Mexico City, suspended in the interstices of hyper-modernity, both in the megacities and in the thousands of small urban explosions that are rendering the peasant villager both urban and displaced. Suspended too between the present and the past, whilst the future is crafted elsewhere by educated elites, these are the inert drivers of China’s industrial expansion. They embody the paradox of hyper-modernity and explosive urbanization, their energies harnessed for the needs of the developmental state, but their own horizons necessarily diminished by the limitations of their education, opportunities and the capacity of development to satisfy an entire population’s ambitions simultaneously. The paradoxical nature of Chinese development is further evident in the re-evaluation of so-called ‘ghost cities’ two years after the Exploding Cities event. Whilst development speculation does lead to empty buildings and investment flight in some areas, in others the ghost city is more accurately understood as a suburb in waiting – as buyers fit out their new homes and wait for other new residents to finish their own (dusty and disruptive) fit-outs before moving in (see Te-Ping, 2013).

Our first evening, back in 2011, taken up by China’s combustible present, we left the theatre and re-entered the streets of Amsterdam, also a city in flux, but one much more obviously concerned with its links to a tangible, articulated and located past. As Lindner and Miriam Meissner indicate in their chapter on ‘decelerating Amsterdam’ in this book, the contemporary city announces its planned shifts in spatio-temporal meaning through visual prompts to place memory for passers-by, especially on building sites where the shift from past to present to future becomes concrete. The interesting contrast is that, where Amsterdam privileges images of the urban past on its hoardings, Chinese developers foreground idealized visions of the new: ‘new city new life’ was Beijing’s Olympic slogan and newness in this slogan has no room for memory work (see Pak Lei Chong, 2012). Walking in Amsterdam and thinking of the power of the visual mnemonic to locate the city in time brought us back not only to the subject of Europe, but to the particular fears which have been shaped, pulverized and concealed in the cities of Europe over the twentieth century.

The profound inertia caused by wartime destruction lies very close to the surface of most major European capitals and trading posts. It is also the prevailing source of inertia in cities still plagued by conflict. As Claire Launchbury explores in her analysis of contemporary Lebanese film, the disappearance of loved ones in war casts the population into a form of suspension, carrying on into a shaky peace without having mourned or known the full extent of their loss. Part of life is not lived, part of the city’s emotional structure is not rebuilt. Meanwhile the reconstruction of postwar and interwar cities into more adaptable, connected and networked hubs for economic development is both a continuation of the reconstruction of confidence and optimism underway since the early 1950s, and a form of denial. Urban transformation creates hope, but it also accommodates new pockets of inertia, for instance in south Beirut, in the outposts built for the working class but instead occupied by migrants in European cities and in the urban pockets of disadvantage and neglect in the United States, occupied by the people that Loïc Wacquant describes as ‘urban outcasts’ (2008). Yet there are ways in which the energy of youth might seize such inertia and performatively transform it into a declaration of survival, just as, more tragically, there are other forms of youthful action that play into the hands of death.

The phenomenon of suspended animation is a biological process that allows some organisms to protract life through difficult times by effecting a transformation from life to seeming death. When the environment improves they transform once more and re-emerge. The concept has been mooted as a medical intervention for human trauma sufferers. It is, if you like, a kind of induced ‘temporary’ immortality. But it is an immortality that imitates death in order to regain life. As Shakespeare’s Juliet discovers in the tomb, if the death is too nearly replicated, it may prove fatal. In two of the chapters in this collection, by Bill Marshall and Shirley Jordan, there are discussions of the suspended animation of (mainly) young people living in global sprawl. This entails both a sociological observation of their opportunity and employment deficits, but also a description of young people’s literal, physical and visceral response to their situation. They jump into the air, sometimes ‘running’ from building to building and sometimes leaping on the spot in extended exuberant movements. These feats of physical defiance occur on walls, on the roofs of buildings and in the interstices of the city’s architecture. Their movements incorporate moments of impossible suspension above the city that lay claim to the immortality of youth. The blockages that social, economic, political and, indeed, architectural structures present to the youth of the global city are thus challenged and suspended in a breath of possibility and beauty. The cover image for this volume is taken from the Denis Darzacq series, La Chute, and was chosen for its resonance with the contradictions between indeterminacy and blockage, playfulness and control, intimacy and anonymity, inertia and mobility that it evokes. A young man has run up and leapt back, to hang suspended – a figure of visceral stillness contrasted against a bright blue municipal wall. On closer inspection one sees that the wall is not painted, but clad in minute blue mosaic tiles, once chosen to brighten up a city environment but now a register of decay. Some tiles are missing, others are chipped, the lower tiles are stained with dirt and the top is marked with water seepage. Within Darzacq’s composition, the wall takes up most of the frame. The scale renders the lone jumper relatively small, but infinitely courageous. He is suspended as though he were answering a challenge to appropriate the wall’s surface as a background to a work of art. If it had been painted rather than tiled, graffiti artists would have already taken this wall for their canvas. Instead, the performative body leaps against it, and then hangs before it, to display the unstoppable presence and cultural value of mobile youth. The performance is a superb embodiment of the nexus of trauma, optimism, inertia and energy that the global city provokes.

The 2011 derivative phenomenon of ‘planking’, suspending oneself by lying still in ever more ridiculous or dangerous places, was a far less political intervention. It was more literally tensile but inert. To ‘plank’ is to hold a position of utter stillness, face down and with arms by one’s sides. It is a riff on an abdominal toning exercise made common through the widespread use of gyms and personal trainers in the more wealthy parts of the urban sphere. Done properly, it is exhausting, as it requires intense muscle control to hold the pose. Planking did not appear to have a social or class-based motivation behind it, but was rather a short-lived fad that spread across the viral architecture of the internet. ‘Planking’ was taught through YouTube rather than on the estates and exurban districts of Paris, London and New York. It was delinked from actual cities by its origins online, yet also served to connect cities in a network of perverse inaction and meaninglessness. The final dramatization of this inaction, by the death of a young man who could not hold the pose and toppled, reputedly because of the use of alcohol, ended its brief regime in the world of memes.

It was on a trip to the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in September 1989 that we first encountered a series of works that have profoundly shaped our understanding of the energy of youth, the inert charisma of the dead and the power of the trained artist’s eye to render that inertia perversely dynamic in shaping an encounter with contemporary urban existence. The previous year, Gerhard Richter had produced his sequence of paintings, October 18, 1977 (1988), to record and remediate the deaths, in Stammheim Prison, of leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Red Army Faction. The title of the series refers to the date on which Gudrun Ensslin, Andreas Baader and Jan-Carl Raspe were found dead in their cells, but the series focuses also on Ulrike Meinhof, who had died in the same prison the previous May. The paintings are monochromatic, blurred and mostly refer to a single subject. The subject is always one of three leaders in the Red Army Faction (Ensslin, Meinhof, Baader) but there are also scenes (Arrest, Cell and Funeral) and a still life (Record Player).

Each painting renders a photograph from the public record – taken by the press or by the prison authorities, and often one which was published in the newspaper, Der Stern – into paint.The effect of remediation is similar to Richter’s later technique of painting over photographs: the subject is accorded an interpretative distance and restored to a dignity that the photograph had betrayed through its original intrusion and subsequent publication. In Hanged (Ensslin hanged in her cell), the subject is remade as a spectre at her own demise. Her body is barely recognizable as such – a thin grey shape suspended in the corner of a room. Suspension is an effective metaphor for the whole event. It reminds us of her physical mode of death, of the doubt her supporters cast over its status as suicide or murder and of the suspension of memory through which the rebuilding of Germany’s cities was funded through profits from companies deeply complicit in the National Socialist war machine 30 years earlier. However confused and misguided the approaches and aims of the BM/RAF, they were undoubtedly spawned in resistance to this complicity. The tragedy and failure of this resistance is the sorrow and the pity at the heart of the image, but it is not immediately available. Beyond the first move of remediation, the further the image is blurred by Richter’s elliptical painting style, the more this distance attracts the eye of the spectator to look into the blur of modern death.

This counterintuitive move can be seen to epitomize the constant blurring of remediated urban experience, which requires a representational approach that can acknowledge the blurred inscrutability of human life, whilst seeking the core of emotionality and affect that makes it human. Seeking the truth of the hanging body in a prison in Stammheim is looking for meaning in a concrete jungle. It is always already too late. Nothing that happens in October 18, 1977 can be separated from the immanence of the urban response to postwar reconstruction, to the idea of the crowds waiting outside and featured in Funeral; or from the print media that reproduces the deaths and distributes them across German cities. It is precisely this insistence that apparent boundaries between institutional, private and public spaces must not create barriers to political meaning that informs those who document youth culture in cities around the world. This relation between death, decay and ethical sociality is debated in Hemelryk Donald’s chapter in this volume on images of death in contemporary film (Chapter 8). The point has similarly been made in regards to the disappearance at the heart of regeneration in Ackbar Abbas’ account of modernity and architecture in Hong Kong (1997), where what is most meaningful is that which has disappeared in the amnesiac construction of new meaning.

In The Hours (2002), a film that draws heavily on the photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank’s understated but uncanny aesthetic in the New York sequences, the key character Robert (Ed Harris), suffering from advanced AIDS, pulls aside the shutters of a darkened apartment and sits astride his window to say farewell to his oldest friend, before tumbling over the edge. The horror of his fall is the common horror of disappearance in and into the city. But that horror also resides in the realization on the part of his old friend (Meryl Streep) that his inertia before dying was greater and more profoundly lonely than the act of dying on the sidewalk several stories below. As he died he became newly visible as a person. Whilst he was the living dead, he was a statistic of infection. His shuttered apartment is reminiscent of the European plague, where those already sick lay dying in houses with a white cross painted on the door.

The city emerges through the interaction between the artist’s eye and the surfaces on which the urban population inscribes its passing, fractious existence. Likewise, the people of the city are made visible through the framing afforded by a collusion of artistic practice and urban traces of presence and absence. In October 18, 1977, the city is minimally present in the portraits, but forcefully so in the contextual scenes. In Arrest, brutalist 1960s buildings loom over the car park where Baader and Raspe were ambushed and detained after a gunfight. In Funeral, the crowd of thousands of mourners, supporters and spectators irrupt into the portraits of the three protagonists of the series, if such a word is permissible in such a context. The women are pictured alive and dead, Meinhof as a younger woman at the point of radicalization and Ensslin on her way to an identity parade in Essen Prison in 1972. These ‘live’ images portray the women looking directly at us. The defiance of their looking emphasizes the youth of the subjects, so that the subsequent portraits of the dead are shocking, moving and perversely resistant to their own passing. Regarding the paintings, whether standing in the gallery in 1989 or flicking through the pages of the later book, the death of the young is ineluctably sad. Richter has rendered these late twentieth-century bogeymen – who were heroic to some, terrorists and murderers to others and misguided to the artist himself – as no more nor less than people who have died in prison, and who were once very young.

In the triptych Tote (Dead) there are three renditions of Ulrike Meinhof’s head and upper torso, laid on the ground after retrieval from her cell, where she was found hanging on 9 May 1972. The presentation is of a head-and-shoulders portrait in profile, but turned on its side, a 90-degree inversion indicating death. Her eyes are closed and a rope burn is clearly visible around her neck. In the first painting (62cm × 67cm) her face is centred, a little to the right. Her cheeks and nose...