- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The founder of the hugely popular PsyBlog demonstrates how to bend habits to your will

Habits are more powerful than your will – if you know how to make them work for you

Two strings are hanging from a ceiling, one at the centre of the room, one near the wall. You’re asked to tie the strings together, but you can’t reach both at the same time. You look around the room and see a table and a pair of pliers. How would you solve the problem?

When confronted with challenges, most people let habits rule them (in this case, ignoring the pliers, the creative tool at your disposal). That is not surprising when you realise that at least a third of our waking hours are lived on auto-pilot – ruminating over past events, clicking through websites trawling for updates and the like. Such unconscious thoughts and actions are powerful. But the habits of the mind do not have to control us – we can steer them.

Drawing on hundreds of fascinating studies, psychologist Jeremy Dean – the mind behind the hugely popular and insightful website PsyBlog – shares how the new brain science of habit can be harnessed to your benefit, whether you’re hoping to eat moreveg, take an evening run, clear out your email backlog, or be more creative when faced with challenges at work and at home.

Habits are more powerful than your will – if you know how to make them work for you

Two strings are hanging from a ceiling, one at the centre of the room, one near the wall. You’re asked to tie the strings together, but you can’t reach both at the same time. You look around the room and see a table and a pair of pliers. How would you solve the problem?

When confronted with challenges, most people let habits rule them (in this case, ignoring the pliers, the creative tool at your disposal). That is not surprising when you realise that at least a third of our waking hours are lived on auto-pilot – ruminating over past events, clicking through websites trawling for updates and the like. Such unconscious thoughts and actions are powerful. But the habits of the mind do not have to control us – we can steer them.

Drawing on hundreds of fascinating studies, psychologist Jeremy Dean – the mind behind the hugely popular and insightful website PsyBlog – shares how the new brain science of habit can be harnessed to your benefit, whether you’re hoping to eat moreveg, take an evening run, clear out your email backlog, or be more creative when faced with challenges at work and at home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making Habits, Breaking Habits by Jeremy Dean in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Consumer Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

Consumer BehaviourPART I

ANATOMY OF A HABIT

1

BIRTH OF A HABIT

This book started with an apparently simple question that seemed to have a simple answer: How long does it take to form a new habit? Say you want to go to the gym regularly, eat more veg, learn a new language, make new friends, practise a musical instrument, or achieve anything that requires regular application of effort over time. How long should it take before it becomes a part of your routine rather than something you have to force yourself to do?

I looked for an answer the same way most people do nowadays: I asked Google. The search suggested the answer was clear-cut. Most top results made reference to a magic figure of 21 days. These websites maintained that ‘research’ (and the scare-quotes are fully justified) had found that if you repeated a behaviour every day for 21 days, then you would have established a brand-new habit. There wasn’t much discussion of what type of behaviour it was, or the circumstances you had to repeat it in, just this figure of 21 days. Exercise, smoking, writing a diary, or turning cartwheels; you name it, 21 days is the answer. In addition, many authors recommend that it’s crucial to maintain a chain of 21 days without breaking it. But where does this number come from? Since I’m a psychologist with research training, I’m used to seeing references that would support a bold statement like this. There were none.

My search turned to the library. There, I discovered a variety of stories going around about the source of the number. Easily my favourite concerns a plastic surgeon, Maxwell Maltz MD. Dr Maltz published a book in 1960 called Psycho-Cybernetics in which he noted that amputees took, on average, 21 days to adjust to the loss of a limb, and he argued that people take 21 days to adjust to any major life change.1 He also wrote that he saw the same pattern in those whose faces he had operated on. He found that it took about 21 days for their self-esteem either to rise to meet their newly created beauty or stay at its old level.

The figure of 21 days has exercised an enormous power over self-help authors ever since. Bookshops are filled with titles like Millionaire Habits in 21 Days, 21 Days to a Thrifty Lifestyle, 21 Days to Eating Better, and finally, the most optimistic of all: 21-Day Challenge: Change Almost Anything in 21 Days (at least it acknowledges that it might be a challenge!). Occasionally, the 21-day period is deemed a little too optimistic and we are given an extra week to transform ourselves. These more generous titles include The 28-Day Vitality Plan and Diet Rehab: 28 Days to Finally Stop Craving the Foods that Make You Fat.

Whether 21 or 28 days, it’s clear that what we eat, how we spend money, or indeed anything else we do, has little in common with losing a leg or having plastic surgery. To take Dr Maltz’s observations of his patients and generalize them to almost all human behaviour is optimistic at best. It’s even more optimistic when you consider the variety amongst habits. Driving to work, avoiding the cracks in the pavement, thinking about sport, walking the dog, eating a salad, booking a flight to China; they could all be habits, and yet they involve such different areas of our lives. But, to be fair, Maltz didn’t invent the 21-day time frame; there are all sorts of stories explaining its origins, most of them standing on science-free ground.

Thanks to recent research, though, we now have some idea of how long common habits really take to form. In a study carried out at University College London, 96 participants were asked to choose an everyday behaviour that they wanted to turn into a habit.2 They all chose something they didn’t already do that could be repeated every day. Many were health-related: people chose things like ‘eating a piece of fruit with lunch’ and ‘running for 15 minutes after dinner’. On each of the 84 days of the study, they logged into a website and reported whether or not they’d carried out the behaviour, as well as how automatic the behaviour had felt. As we’ll soon see, acting without thinking, or ‘automaticity’, is a central component of a habit.

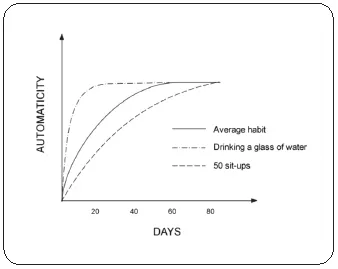

So, here’s the big question: how long did it take to form a habit? The simple answer is that, on average, across the participants who provided enough data, it took 66 days until a habit was formed. And, contrary to what’s commonly believed, missing a day or two didn’t much affect habit formation. The complicated answer is more interesting, though (otherwise this would be a short book). As you might imagine, there was considerable variation in how long habits took to form depending on what people tried to do. People who resolved to drink a glass of water after breakfast were up to maximum automaticity after about 20 days, while those trying to eat a piece of fruit with lunch took at least twice as long to turn it into a habit. The exercise habit proved most tricky with ‘50 sit-ups after morning coffee’, still not a habit after 84 days for one participant. ‘Walking for 10 minutes after breakfast’, though, was turned into a habit after 50 days for another participant.

The graph shows that this study found a curved relationship between repeating a habit and automaticity. This means that the earlier repetitions produced the greatest gains towards establishing a habit. As time went on these gains were smaller. It’s like trying to run up a hill that starts out steep and gradually levels off. At the start you’re making great progress upwards, but the closer you get to the peak, the smaller the gains in altitude with each step. For a minority of participants, though, the new habits did not come naturally. Indeed, overall the researchers were surprised by how slowly habits seemed to form. Although the study only covered 84 days, by extrapolating the curves it turned out that some of the habits could have taken around 254 days to form – the better part of a year!

On average, habit formation took 66 days. Drinking a glass of water reached maximum automaticity after 20 days; for 50 sit-ups, it took longer than the 84 days of the study.

What this research suggests is that taking 21 days to form a habit is probably right, as long as all you want to do is drink a glass of water after breakfast. Anything harder is likely to take longer to become a quite strong habit, and, in the case of some activities, much longer. Dr Maltz and his cheerleaders weren’t even close, and all those books promising habit change in only a few weeks are grossly optimistic. Of course, this study opens up a whole new set of questions. The participants were only trying to adopt new habits; what about our existing habits? How much better might they have done using tried-and-tested psychological techniques? And this study doesn’t really tell us what a habit feels like, how we experience it, or where it tends to happen.

What do we actually do all day long? Some busy days slip by in a flash and we remember little. Whether at work or idling around at home, it would be fascinating to know exactly how our time is spent and which parts of it are habitual. Unfortunately, there’s a very good reason why we tend to be awful at recalling habitual behaviour, which is to do with its automaticity. So psychologists use diary studies, which give a much more accurate picture of what people are up to than we can get from memory. In one study led by habit researcher Wendy Wood, 70 undergraduates at Texas A&M University were given a watch alarm.3 Every hour while they were awake, it reminded them to write down what they were doing, thinking, and feeling, right at that very moment. The idea was not just to build up a list of activities, but to see the context in which they occurred. Across two separate studies, the researchers found that somewhere between one-third and half the time people were engaged in behaviours which were rated as habitual. This suggests that as much as half the time we’re awake, we’re performing a habit of one kind or another. Even this high figure may well be underestimated, since it’s based only on young people whose habits haven’t had much of a chance to become ingrained.4

So, what were participants in Wood’s research up to? Since they were students, the largest category was studying. This included attending lessons, reading, and going to the library, which made up 32% of the diary entries. Amongst these activities, about one-third were classified as habitual. The next category was entertainment, which participants were engaged in for 14% of the time. This included things like watching TV, using the Internet, and listening to music. This time, the percentage of habitual activities went up to 54%. Next on the list were social interactions, which made up 10% of the entries and 47% of which were classified as habitual behaviours. The category in which the behaviours were least habitual was cleaning, down at only 21%, while the category which was most habitual was going to sleep and waking up at 81% (at least they weren’t hiding their lazy, slovenly ways!).

More important than precisely what they were doing (especially for those of us who aren’t students), are the characteristics of habits. What does it feel like? What’s going on in our minds? What emerged from this study, as it has from others, are three main characteristics of a habit. The first is that we’re only vaguely aware of performing them, like when you drive to work and don’t notice the traffic lights. You know that some part of your mind was attending to them, along with other road-users and the speed limit, but often you can’t specifically remember doing so. In Wood’s study, participants reported exactly this vagueness about their habitual behaviour. While they were relaxing, watching TV, or brushing their teeth, they reported thinking about what they were doing only 40% of the time. It’s one of the major benefits of a habit: it allows us to zone out and think about something else, like planning a weekend trip. Habits allow the conscious part of our minds to go a-wandering while our unconscious gets on with those tedious repetitious behaviours. Habits help protect us from ‘decision fatigue’: the fact that the mere act of making decisions depletes our mental energy. Whatever can be done automatically frees up our processing power for other thoughts.

A habit doesn’t just fly under the radar cognitively; it also does so emotionally. And this is the second characteristic that emerged: the act of performing a habit is curiously emotionless. The reason is that habits, through their repetition, lose their emotional flavour. Like anything in life, as we become habituated our emotional response lessens. The emotion researcher Nico Frijda classifies this as one of the laws of emotion, and it applies to both pleasure and pain.5 Activities we once considered painful, like getting up early to go to work, become less so with repetition. On the other hand, activities which excite or give us pleasure initially, like sex, beer, or listening to Beethoven’s Seventh, soon become mundane. Of course, we fight against the leaking away of pleasure, sometimes with success, by seeking variety. This is why some people feel they have to keep pushing the boundaries of experience just to get the same high.

None of this means we don’t feel emotion while performing a habit, it’s just that the feelings we experience usually have less to do with the habit and more to do with where our minds have wandered off to. Wood’s research found this exact pattern in participants’ reports of their emotional experience. Compared with non-habitual behaviours, when people were performing habits their emotions tended not to change. In addition, the emotions that people did experience were less likely to be related to what they were doing than when their activities were non-habitual. The fact that habitual behaviour doesn’t stir up strong emotions is one of its advantages. Participants in this study felt more in control and less stressed while performing habits than they did enacting non-habitual behaviours. The moment participants switched to non-habitual behaviours, their stress level increased.

The third important characteristic of a habit is so obvious that often we don’t notice it. Perhaps this is partly a result of the automatic nature of habits. Take some typical daily routines: You get up in the morning, go to the bathroom, and have a shower . . . Later you’re in the car when you turn on your favourite radio station . . . Then, at the coffee shop, you order a blueberry muffin . . . The connection is context. We tend to do the same things in the same circumstances. Indeed, it’s partly this correspondence between the situation and behaviour that causes habits to form in the first place.

The idea that we create associations between our environment and certain behaviours was memorably demonstrated by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. In Pavlov’s most famous research, carried out on dogs, he created an association between being fed and the sound of a bell ringing. Then, after a while, he tried ringing the bell without feeding the dog. He noticed that the dog began to salivate anyway. The toilet, car, and coffee shop are like Pavlov’s bell, unconsciously reminding us of long-standing patterns of behaviour, which we then enact again, in exactly the same way as before. This is backed up by research on humans that shows that people tend to perform the same actions in the same contexts. In the diary study described above, most of the behaviours, like socializing, washing, and reading, were carried out in the same place.

It becomes clear just how much context is important for habit whenever you move house or get a new job. Once in a new home, it’s suddenly difficult to do the simplest of jobs. Making a sandwich becomes an ordeal as you have to think consciously about where the knives and plates are. It’s not just simple tasks that become more difficult; it’s all your usual routines. From getting up in the morning to going to bed at night, so many tasks feel like they’re being done for the first time. You may even find yourself trying to carry out your old habits in your new home, to no avail: because everything has moved, suddenly those ingrained ways of behaving fail you. The same goes for new jobs. Where once you glided around the workplace on autopilot from one task to the next, in the new job you feel like a fish out of water.

Psychologists have seen how important context is during research on how people cope with changes to their environment. In one study, students’ habits were tracked as they transferred to a new university.6 They were asked how often they watched TV, read the paper, and exercised both before the move and afterwards. They were also asked about the context in which these habitual behaviours were performed. How did they perceive the context, where were they physically, and who was with them at the time? The answers to these questions built a picture of whether the context had really changed with the move from one location to another. For example, it’s possible that although a physical location changes, the overall context doesn’t. Like hotel rooms, one hall of residence can look much like another; so it might not feel that things have changed much.

What the participants reported as they moved from one university to another was that context was important in habit change. They found that if they wanted to cut down their TV and increase their exercise, it was easier to do so after the move. This is because new surroundings don’t have all the familiar cues to our old habits. Without these cues, our autopilot doesn’t run so smoothly and our conscious mind keeps asking us what to do. That’s why moving house is like going on holiday: without your established routines, you have to keep consciously thinking about what you’re going to do now. The same thing happened to these students. Instead of automatically watching TV or reading the newspaper, they were more likely to think, ‘What did I plan to do today?’ and ‘What do I actually want to do now?’ As a consequence, a world of possibility opens up.

The rather bland word ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Epigraph page

- Contents

- PART 1: ANATOMY OF A HABIT

- 1. Birth of a habit

- 2. Habit versus intention: an unfair fight

- 3. Your secret autopilot

- 4. Don’t think, just do

- PART 2: EVERYDAY HABITS

- 5. The daily grind

- 6. Stuck in a depressing loop

- 7. When bad habits kill

- 8. Online all the time

- PART 3: HABIT CHANGE

- 9. Making habits

- 10. Breaking habits

- 11. Healthy habits

- 12. Creative habits

- 13. Happy habits

- … now read on at PsyBlog

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Index