eBook - ePub

Drunk Tank Pink

Adam Alter

This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drunk Tank Pink

Adam Alter

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

'Drunk Tank Pink' is a particular shade of pink. In 1979 psychologists discovered that it has an extraordinary effect: if you stare at it for two minutes, you dramatically weaken in strength.In this brilliant study of the strange recesses of our minds, Adam Alter reveals the world is full of such hidden forces that shape our every thought, feeling and behaviour – without us ever realizing.

- Some letters in product names make us more likely to buy them (nearly all successful brands contain a 'k' sound)

- We're more likely to be critical if we write in red rather than green biro

- Your first report at school can determine your future career

Understanding these cues is key to smarter decision-making, more effective marketing, and better outcomes for our selves and our societies. Prepare for the most astounding and fast-paced psychology book since Blink and Predictably Irrational.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Drunk Tank Pink an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Drunk Tank Pink by Adam Alter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Advertising. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE WORLD WITHIN US

1.

NAMES

The Birth of Nominative Determinism

When Carl Jung, one of the most famous psychiatrists of the twentieth century, once wondered why he was so fixated on the concept of rebirth, the answer arrived in a flash of insight: his name meant “young”, and from birth he had been preoccupied by the concepts of youth, ageing, and rebirth. Other renowned psychiatrists of the early twentieth century embarked on very different research programmes, but as Jung explained, “Herr Freud (whose name means Joy in German) champions the pleasure principle, Herr Adler (Eagle) the will to power, Herr Jung (Young) the idea of rebirth”. As far as Jung was concerned, the names we’re given at birth blaze a trail that our destinies tread for years to come.

Many years later, in 1994, a contributor to the Feedback column in the New Scientist magazine labelled the phenomenon nominative determinism, literally meaning “name-driven outcome”. The writer noted that two urology experts, Drs A. J. Splatt and D. Weedon, had written a paper on the problem of painful urination in the British Journal of Urology. Similar so-called aptronyms abound. The current Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales is Justice Igor Judge; his colleague Lord Justice Laws is a judge in the Court of Appeal. In the realm of athletic pursuits, Anna Smashnova was a professional Israeli tennis player, Layne Beachley is a seven-times world-champion surfer, Derek Kickett was an Australian Rules footballer, Stephen Rowbotham was an Olympic rower for Britain, and Usain Bolt is the fastest man in the world over the hundred-metre and two-hundred-metre distances. Some names herald less auspicious destinies: Christopher Coke is a notorious Jamaican drug dealer, and the rapper Black Rob was sentenced to seven years in prison for larceny. It’s tempting to dismiss these anecdotes as scattered coincidences, but researchers have shown that our names take root deep within our mental worlds, drawing us magnetically towards the concepts they embody.

Indeed, names convey so much information that it’s easy to forget that they don’t have natural meanings as, say, numbers do. The number 10 will always have the same meaning regardless of whether you call it ten, diez, dix, or dieci, which is why scientists seeking extraterrestrial contact devise mathematical languages to communicate with alien life forms. A single pulse of noise will always signal one, or unity, whereas two pulses will always signal two. That universal property doesn’t apply to names, which are language-bound. Jung’s witty observation that Freud’s name compelled him to “champion the pleasure principle” registers only if you know that Freud means “joy” in German. Names are powerful, then, only when they’re associated with other, more meaningful concepts. Parents from certain cultures embrace this idea when naming their children. The Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan grew into his name handsomely, and his wife, Patience, was named after a trait that first ladies sorely need as their husbands ascend the political ladder. According to one Nigerian proverb, “When a person is given a name, his gods accept it”, which explains why exhausted parents sometimes name their children Dumaka (literally, “help me with hands”) or Obiageli (“one who has come to eat”). The Mossi tribespeople of Burkina Faso have taken nominative determinism one step further, giving their children strikingly morbid names in a desperate bid to placate fate. Parents who have already lost more than one child (the Mossi infant mortality rate is tragically high) have been known to name their subsequent children Kida (“he is going to die”), Kunedi (“dead thing”), or Jinaku (“born to die”).

Other parents do everything they can to protect their children from the tide of nominative determinism. In his native Russian tongue, Vyacheslav Voronin’s name means “slave”. As far as associations go, that’s a significant cross to bear, so Voronin and his wife, Marina Frolova, decided to save their newborn son a similar indignity. Slight and sandy-haired, the boy was born in the summer of 2002 during a spate of terrible Russian floods. True to their promise, Vyacheslav and Marina chose a generic name designed to be devoid of meaning: BOHdVF260602. Although the name seems meaningless, BOHdVF260602 stands for “Biological Object Human descendant of the Voronins and Frolovas, born on June 26, 2002”. For the sake of practicality, young BOHdVF260602 responds to the name Boch (roughly pronounced “Bawtch”). Vyacheslav claims that Boch’s name “will make his life easier, so he won’t interact with those idiots who think one’s name defines his appearance. Every person who gets a traditional name is automatically linked to his historic background. This way, my son will be devoid of his father’s legacy.”

People name their children using all sorts of rules and approaches. Sometimes they borrow names from historical or literary heroes, sometimes they perpetuate ancestral naming traditions, and sometimes they just like how a name sounds or the fact that it reminds them of something appealing. In all cases, though, the otherwise meaningless name acquires meaning because it’s associated with other concepts that are themselves meaningful. The power of association explains why Adolf, a common boy’s name once associated with Swedish and Luxembourger kings, plummeted in popularity during and after World War Two. Meanwhile, the name Donald fell from favour when Donald Duck appeared in the 1930s, and parents stopped naming their sons Ebenezer in the 1840s when Charles Dickens’s newly published book, A Christmas Carol, featured the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge. What makes Boch’s name so unusual is that his parents went to great lengths to avoid choosing a name with even minimal associations. Though Vyacheslav was determined to spare Boch the teasing that he endured as a boy, it’s hard to imagine Boch emerging from childhood without being teased about his name at least occasionally. The odds are stacked higher still, as the Russian birth registry has refused to record Boch’s full name. According to Tatyana Baturina, a representative of the registry, “You can call your child a ‘stool’ or a ‘table’. A child has a right to such a name. But one has to use common sense. Why should one suffer from the parents’ choice? He will go to kindergarten, and then to school, and he will be mocked, all because of his name.” It’s not immediately clear that naming a boy “Stool” demonstrates more common sense than naming the boy “BOHdVF-260602” and he’d be unlikely to escape torment with either name.

Scattered anecdotes aside, do names really affect major life outcomes? Would Usain Bolt run more slowly with the name Usain Plod? Would urologists Splatt and Weedon have pursued different medical specialities with less “urological” names? These thought experiments are impossible to conduct in reality, so researchers have devised other clever techniques to answer the same question.

Names Influence Life Outcomes

Every name is associated with demographic baggage: information about the bearer’s age, gender, ethnicity, and other basic personal features. Take the name Dorothy, for example. Imagine that you’re about to open your front door to a stranger named Dorothy. What kind of person would you expect Dorothy to be? First, Dorothy is more likely to be an elderly lady than a young woman. Dorothy was the second most popular girl’s name in the 1920s, and fourteen out of every hundred baby girls born during that decade were named Dorothy. That multitude of Dorothys is now approaching the age of ninety. In contrast, the name is almost non-existent among girls born during the twenty-first century. The reverse is true of the name Ava, which was almost non-existent before the twenty-first century but dominates the most recent US Census. Apart from age, names convey ethnic, national, and socio-economic information. Base rates suggest that Dorothy and Ava are almost certainly white, Fernanda is likely to be Hispanic, and Aaliyah is probably black. Luciennes and Adairs tend to be wealthy white children, and Angels and Mistys tend to be poorer white children. Likewise, Björn Svensson, Hiroto Suzuki, and Yosef Peretz are almost certainly males of Swedish, Japanese, and Israeli descent respectively. More narrowly, Waterlily and Tigerpaw sound like the offspring of ageing hippies, while Buddy Bear and Petal Blossom Rainbow sound like names that celebrities might choose for their children. (They are; those are the names of two of celebrity chef Jamie Oliver’s four children.)

One reason why personal names are so important, then, is that they allow people to categorize us almost automatically. In their book Freakonomics, Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner describe a strong relationship between a mother’s education and the names she chooses for her children. White boys named Ricky and Bobby are less likely to have mothers who finished college than are white boys named Sander and Guillaume. Since education improves spelling, it comes as no surprise that white boys named Micheal and Tylor tend to have less well-educated mothers than do white boys named Michael and Tyler. Similar patterns emerge when you compare a child’s name with family household income. White girls named Alexandra and Rachel tend to be wealthier than white girls named Amber and Kayla.

Of course, it’s important to note that the relationships between income, education, and naming preferences are not causal—just because poorer children tend to have consistently different names from wealthier children doesn’t mean that girls named Alexandra are financially better off because they’ve been named advantageously. A more likely alternative is that people from different socio-economic and educational backgrounds inhabit different cultural environments, which in turn shape their preferences for particular names. (Chapter 6 considers the relationship between culture and preferences more deeply.) For example, US residents who live in the southern states tend to be poorer than residents in the northern states, and, relative to Northerners, Southerners also tend to prefer the name Bobby. The marked cultural differences between Northerners and Southerners probably explain both their distinct naming preferences and the income gap that separates the two groups. The dark side of these relationships is that over time, people meet many more poor Bobbys than wealthy Bobbys, and many more wealthy Sanders than poor Sanders, so they start to form strong associations between the name and important life outcomes. Consequently, a seasoned recruiter who considers two job application folders—one submitted by Sander Smith and the other by Bobby Smith—will presume that Sander’s parents are wealthier and better educated than Bobby’s parents even before he opens the folders.

So, what would happen if you could turn back the clock and rename a child who was given a typically black name with a typically white name instead? Would the child’s life be any different? Short of building a time machine, there’s no way to test this conjecture in its purest form, but two economists have done the next best thing. They wondered whether two job applicants who were identical, except for the blackness or whiteness of their names, might inspire different responses from firms that advertised positions online. The researchers responded to five thousand job ads in Boston and Chicago and varied two features of the attached CV’s: their quality (some were strong and others were weak), and the blackness or whiteness of the names (some were typically white names and others were typically black names). It’s no surprise that the stronger CVs yielded more responses, but names also had a marked effect. Emilys, Annes, Brads, and Gregs fared better than Aishas, Kenyas, Darnells, and Jamals, even when their applications were identical on every important indicator of applicant strength. In fact, fictional applicants with white names received responses on 10 percent of their applications, whereas applicants with black names received responses on only 6.5 percent of their applications—a 50 percent difference. Put another way, on average white applicants only need to send out ten applications to get a single response, but black applicants need to send out fifteen for the same outcome. Also disturbing was the finding that a stronger application helped white applicants but did very little to improve the prospects of black applicants. Whereas employers rewarded stronger white applicants with 27 percent more responses than weaker white applicants, stronger black applicants received only 8 percent more responses than weaker black applicants (and 27 percent fewer even than weak white applicants). It’s impossible to get a job without clearing the first hurdle, so these results bode ill for the state of racial bias in a society that some pundits describe as “post-racial”.

If the damaging stereotypes that produced these disturbing results vanished, would names lose their power to shape important life outcomes? The Voronins must have believed so when they named their son BOHdVF260602, a name chosen because it was free of the usual demographic baggage. As it turns out, the Voronins were addressing only part of the issue. Our own names influence us even in the absence of other people. According to Belgian psychologist Jozef Nuttin’s classic account, people feel a sense of ownership over their names. People tend to like what belongs to them, so Nuttin found that people preferred the letters that populated their names more than the letters that were absent from their names. In one study, Nuttin asked two thousand people who spoke one of twelve different languages to choose the six letters they liked most from their language’s written alphabet—the letters they found most attractive without investing much thought in the process. Across the twelve languages, people circled their own name letters 50 percent more often than they circled name-absent letters. So, had Jozef Nuttin completed the study himself, he would have been 50 percent more likely to circle the letter Z than would have a fictitious Josef Nuttin, for whom Z would not have held a special personal meaning.

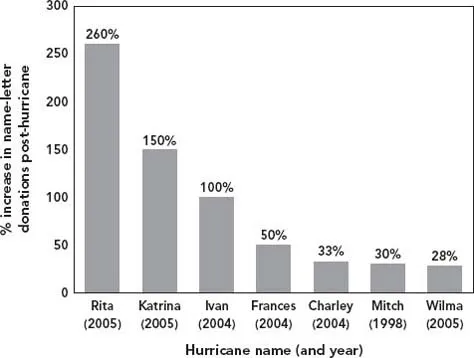

The magnetic attraction we feel towards our name letters contributes to a range of surprising outcomes. People donate to charities for all sorts of reasons: because they have a personal link to the cause, because it tugs at their heartstrings, and sometimes because they honestly believe the cause deserves their support. These rationales are easy to defend, but psychologists have shown that people tend to donate more often and more generously to causes that share their initials. The researchers examined Red Cross donation records following seven catastrophic Atlantic Ocean hurricanes that hit the United States between 1998 and 2005. There’s no natural shorthand for referring to tropical storms, so the National Hurricane Center has labelled each tropical storm since the 1950s with a proper name. As you might expect based on the name-letter effect, people are drawn to hurricanes that share their initials. For example, people with K names donated 4 percent to all disasters before Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, but 10 percent of all Katrina donations came from K-named people, a 150 percent increase. You might be wondering whether people named Katrina, Kate, Katherine, Katie, or any other “Kat” names were responsible for the change. They weren’t; the effect was just as strong when those people who shared more than just the first letter with Katrina were removed from the analysis. The same results were true for a range of hurricanes.

The positive association we have with our names explains most name-letter effects, but sometimes our initials also inspire thoughts and behaviours that arise through force of habit. One of the major differences between people with A surnames and people with Z surnames is where those names fall on default alphabetical lists. For better or worse, teachers often call on students with A surnames before they call on students with B surnames, and so on through the alphabet till the Zahns, Zolas, and Zuckermans are called on last. Some teachers are sensitive to this issue, so they occasionally start at the bottom of the alphabet—but more often than not, they begin with A and end with Z. In a series of clever studies, two psychologists tested the idea that people whose family names were at the end of the alphabet might respond more quickly to scarce opportunities than their beginning-of-the-alphabet counterparts. Since people with N–Z names habitually wait behind people with A–M names, the researchers guessed that N-to-Zers might be chronically quicker to respond to limited opportunities because they so often have to wait their turn. That’s exactly what they found when they offered a limited number of free basketball tickets to a group of graduate students. The further down the alphabet the students’ family names, the quicker they were to respond. In another study, the researchers found that PhD students with later-letter names were quicker to post their job-search materials online than were students with earlier-letter names. In fact, the students who posted their materials during the first three weeks had an average family-name letter of M (the twelfth letter), whereas students who posted their materials after the first three weeks had elapsed had an average family-name letter of G (the seventh letter). This last-name effect, as the researchers call it, illustrates just one more way that names subtly influence our lives.

For each of the seven hurricanes examined, the proportion of Red Cross donations from people whose names shared the hurricane’s initial increased immediately after the hurricane. For example, M-named people made up 30 percent more of the donor population during the two-month period after Mitch devastated Honduras and Nicaragua in 1998 than during the six-month period before the hurricane struck.

Names, then, have the capacity to shape our outcomes because they’re tied to important concepts that have real meaning...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue

- Part One: THE WORLD WITHIN US

- Part Two: THE WORLD BETWEEN US

- Part Three: THE WORLD AROUND US

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Index