![]()

During the Eclipse

Carter Stone and W. P.

C. S.: Why after all did you begin to write on art instead of sticking to painting?

W. P.: It seemed more important to me to try to clarify a little the present confusion in matters of art than to paint a few more or a few less pictures.

C. S.: But as a painter wouldn’t you, even unconsciously, take the side of that particular direction in painting to which your own work belongs? For example, wouldn’t you naturally take the standards of the School of Paris for the standard of painting itself?

W. P.: I don’t see how I could, since nothing has ever existed that could be called the “School of Paris.” C. S.: What do you mean?

W. P.: The “School of Paris” was only a slogan invented by picture dealers jealous of the dressmakers. They, too, wanted to establish a luxury article marked “imported from Paris.”

C. S.: But all the same contemporary art did know its apogee in Paris.

W. P.: As a matter of fact it did. Only one must not mix things up. It is precisely because there people were not interested in a Parisian art, because there, better than elsewhere, it was understood that modern art is in essence international, that Paris could become the cultural capital, the artistic center of the world. There were, of course, other good reasons besides why a great number of artists from all over found their most favorable climate there. However, others and some of the most influential—Kandinsky, second only to Picasso, and Klee and Moore for example, were not formed in Paris. The last century is different; then there did exist a distinctly French school.

C. S.: It is true, of course, that any artist essentially limited by national qualities or defects belongs to the past. Which doesn’t prevent there being, as long as there are tourists, people who will paint the little Indian with the big cactus. At home too, there is a kind of crustacean walking backward toward an “American art,” but certainly tomorrow no one will think of art in terms of European or American.

W. P.: The same chauvinistic tendencies always flourish more in time of war and more than ever now that the lack of understanding of the function of art adds to the general intellectual confusion.

C. S.: Certain critics pretended to explain that function by sociological analysis. I know they did not succeed, because instead of developing the Marxist concept, they applied it rather mechanically. That is, they overlooked the reciprocal interactivity between the intellectual interpretation and the material transformation of the world, they hypnotized themselves with an economic a priori as arbitrary as the old spiritualist a priori. After all it is due to the imagination of some individuals that economic conditions have ever changed and go on changing. Why not admit that the dance of the primitive hunter which exalts his courage is as important for the material result of the hunt as his knowledge of arrow-making?

W. P.: The very idea that art does not evolve in a metaphysical vacuum but has something to do with the society in which it is produced seemed absolutely luminous after the ineptness of the idealistic aesthetic theories. Thanks to this discovery critics with historical pretensions believed themselves clever in replacing the Monkey Theory: art as an imitation of nature, by the Mirror Theory: art as a reflection of society. What a discovery that the masterpiece of Seurat, A Sunday afternoon at la Grande Jatte, has something to do with the Sunday walks of the Parisian bourgeois of the end of the nineteenth century! Thus being able to discern a few figures dressed as bourgeois in the pictures of Seurat and others, there were penetrating critics who jumped to the conclusion that these pictures reflect bourgeois leisure.

C. S.: But art is nevertheless always conditioned by society?

W. P.: Naturally. Every activity of an individual is always, directly or indirectly, conditioned by surroundings. Economically art is always conditioned by society, whether society favors, ignores or even oppresses it. But that does not mean that an individual cannot put himself out of an accepted standard society, that he cannot work in large measure on concepts radically different from those around him. As a matter of fact it is in that way that the few heroic individuals, precursors and discoverers in whatever field, have always worked. And instead of losing themselves in subtleties as to what can and what cannot be defined as “reflection” or “social reaction,” our critics should have seen the tremendous significance in the principal characteristic of all modern art, that is that it has been created outside of contemporary society. It is obvious, at least for anyone without dogmatic spectacles, that from Shelley to van Gogh all creative artists have worked if not against at least outside of bourgeois society. The bourgeois of the end of the nineteenth century did not recognize his Sunday promenade in the Grande Jatte*; he did not recognize himself for the good reason that the statuesque people of Seurat had as little to do with him as the people of Poussin with Greece, or the Negroes painted by Picasso with those of Africa; which of course the critics of his time understood when they found Seurat’s people more like Egyptian statuary than like their Parisian contemporaries.

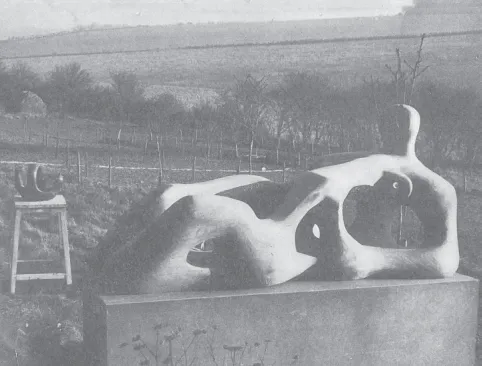

Henry Moore. Reclining Figure. 1939. Repoduced by permission of The Henry Moore Foundation.

C. S.: It wouldn’t seem then, that because Cézanne had an immoderate taste for apples, nor because his subconscious was overcome by changes in the import duties on agricultural products, nor because the enlightened bourgeois was being converted to vegetarianism, that fruit predominates in his paintings. And it isn’t, perhaps, any more intelligent to infer from occasional representations of bourgeois leisure by impressionists and neo-impressionists to ideological parallels of these painters with bourgeois society, than to infer a special taste for music and for pipe-smoking from the fact that the cubists painted so many pipes and guitars.* But the question remains why such a painter at such a time prefers certain objects rather than others for his plastic meditations.

*It is forgotten today how recent the great renown of Seurat is. He did not sell his masterpieces; La Grande Jatte remained until 1925 in the possession of Lucie Cousturier, his pupil, who still in 1926 speaks of Seurat as of a “great unknown painter.” Seurat, by Lucie Cousturier, page 7 (Ed. Crès, Paris 1926).

W. P.: I think the question is not well put under that form. One should rather ask how such a painter uses such an object as a painter. The why of a very personal choice escapes us, as it perhaps escapes the painter himself. It is evident that there is a connection between horsebreeding in Tuscany and the equestrian battles painted by Uccello, just as there is between the leisure of Parisians and certain works of Seurat; that does not mean to say that the art of Uccello was essentially conditioned by horses, any more than that of Seurat by the bourgeoisie, but only that certain of their works, among other things, presupposed the existence of horses and of the bourgeoisie. Manet, the least audacious of the great painters of the second half of the last century, was the only one to participate to a certain degree in the life of the “society” of his time and to paint a contemporary historical subject. However, his Execution of the Emperor Maximilian is manifestly inspired by reminiscences of Goya, and not by any specific interest in the event. And one would come to rash conclusions about the bourgeois manners of the day if one were to assume they were reflected in the Déjeuner sur l’herbe, forgetting that this picture repeats one of Raphael’s compositions. Renoir’s paintings “reflect” much more Watteau and Fragonard than contemporary content, just as there is more relation between the nudes of Cézanne and of El Greco than there is between a nude of Cézanne and one by Renoir. Instead of making false connections between the plastic interest of a painter in a subject and his “social reaction,” it is necessary to understand that, by their very indifference toward the subject as such, modern artists express their disdain for present society. Of course, for a thoroughgoing analysis of the art of a period it is indispensable to find its connections with the ensemble of problems, economic as well as intellectual. Only it is better not to make such connections than to make false ones.

*It may be said in passing that none of the founders of cubism smokes a pipe or plays the guitar.

C. S.: It is easy to see that modern art has survived not because of, but in spite of capitalism, and this does away with the stupid reproach that the innovating artist works only for millionaires. It is no more intelligent to reproach painters with working for the rich because under the present system their works become sometimes the object of commercial speculation, than to reproach Marx with having written for book collectors because the first edition of his manifesto sells today for more than a thousand dollars.

W. P.: There was perhaps too much excitement over the fact that before the war there were, in the whole world, a half-dozen good painters who managed to earn almost a tenth of what a movie star gets. One forgets too easily that except for these men, other painters of equal worth lived and still live miserably; that it is not even enough, for a painter, to have gained a worldwide reputation in order to live modestly from his work.

C. S.: While the bourgeoisie, at its height, paid its own artists well. At the same time that Monet, van Gogh, Gauguin and so many others who have made the history of art were more or less starving, Meissonnier, Kaulbach and other forgotten coiffeurs were paid enough to live like princes. It has been very well said apropos of the Vanderbilt collection that with a fraction of the amount which that collector spent for nameless daubs, there could have been made one of the most beautiful collections of nineteenth-century painting. It is not as bad now because commercialization has made enough progress to make profits even on modern art, and capitalists have discovered the trick of avoiding the income tax and at the same time playing Medici by founding museums. Nothing is lost, since at a given moment the museums can be transformed into agencies of imperialist propaganda.

W. P.: Not to be able to do anything, yet at least to change this state of things does not mean that we are dupes.

C. S.: And art for the masses?

W. P.: There can be no art for the masses as long as art remains practically inaccessible to the masses. In the actual state of affairs the masses have as little means of knowing works of art as they have of many other good things. Brancusi told me one day how delighted he was at the reaction of some workers seeing his sculptures. Instead of quibbling as to whether people would understand or would not understand, it would be better to ask how many people have a chance to see the work of the greatest sculptor of our time. Here as elsewhere it is much less a problem of production than of distribution; it doesn’t involve producing a pseudo-proletarian art but finding practical means of making authentic works available.

C. S.: But it certainly won’t be through the routine of the galleries or the mentality of the picture dealers.

W. P.: The picture dealers, neither worse nor better than other businessmen, can’t do much; for an art outside daily life, they were the indispensable intermediaries.

C. S.: Why “were”? Do you think they aren’t any more?

W. P.: As a matter of fact, I believe that if not their days, at least their years are numbered.

C. S.: But who will replace them?

W. P.: The picture editors, bookstores, libraries and lecture rooms. Tomorrow pictures will be edited like books, or, if you prefer, good cheap reproductions and television will do for the propagation of painting what records and radio did for music. In the same way for sculpture new material and processes of reproduction will permit an edition in quantities, a mass production anticipated by casting. In that way it will not be in the lowering of the standard of artistic production by enterprises of the department-store type, but in finding adequate means for the mechanical multiplication of works of value, that art will reach the masses.

C. S.: But doesn’t it seem likely that like books, the bestsellers will be mostly vulgar and mediocre things?

W. P.: Probably, but the artist will not need to make bestsellers in order to live from his work. The problem is in finding the material possibilities of producing and the means of communicating for those who have something to say; one will never be able to stop people prostituting themselves.

C. S.: The public likes the immoral artist and moralizing art, just as it is bad lives that make the good biographies. . . .

W. P.: The artist should learn his responsibilities; he must learn to respect himself and to make himself respected. The days of intellectual bohemianism are over. Those who think themselves the court jesters of the century finish as buffoons. The examples are under our noses. On the other hand, since we don’t ask for quixotic martyrs, the line of dema...