![]()

1 Management of Crops to Prevent Pest Outbreaks

Claudia Daniel,* Guendalina Barloggio, Sibylle Stoeckli, Henryk Luka and Urs Niggli

Research Institute of Organic Agriculture, Forschungsinstitut für biologischen Landbau (FiBL), Frick, Switzerland

Introduction

Organic farmers face the same potentially severe pest problems as their colleagues in integrated pest management (IPM) and conventional farming systems. However, approaches to manage the pest insects are different because the aim of organic farming is a holistic system perspective rather than simple reductionist control approaches. Organic cropping systems are designed to prevent damaging levels of pests, thus minimizing the need for direct and curative pest control (Peacock and Norton, 1990). Within this chapter, we will briefly explain the standards for organic farming, which also set the framework for pest control. We present a conceptual model for pest control in organic farming and describe the influence of functional agrobiodiversity and conservation biological control on pest management. We focus on the use of preventive strategies and cultural control methods. The system approach is illustrated with examples in organic Brassica vegetable and oilseed rape production, because these economically important crops (Ahuja et al., 2010) are attacked by a broad range of different pest insects (Smukler et al., 2008; Ahuja et al., 2010) and show different levels of tolerance. Economic thresholds for pests on oilseed rape are usually higher than on vegetables. Therefore, less control is used in oilseed rape which might lead to the build-up of large pest populations, threatening nearby vegetable fields. With the increasing area of oilseed rape production, pest problems in these crops are likely to increase.

Standards for Organic and IPM Production: Similarities and Differences

Organic farming

Organic farming is regulated by international and national organic production standards, such as the IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements) Norms (IFOAM, 2012), Codex Alimentarius (FAO and WHO, 2007), or European Union (EU) regulation (EC, 2007). Organic standards all have the same principal norms for plant production as described in the Codex Alimentarius:

Organic agriculture is a holistic production management system which promotes and enhances agroecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity. It emphasizes the use of management practices in preference to the use of off-farm inputs, taking into account that regional conditions require locally adapted systems. This is accomplished by using, where possible, cultural, biological, biotechnical, physical and mechanical methods, as opposed to using synthetic materials, to fulfil any specific function within the system.

(FAO and WHO, 2007)

Thus, the maintenance of plant health primarily relies on preventative measures, such as: (i) the choice of appropriate species and varieties resistant to pests and diseases; (ii) appropriate crop rotations, cultivation techniques, mechanical and physical methods; and (iii) the protection of natural enemies of pests. In the case of an established threat to a crop, plant protection products may only be used if they have been authorized for use in organic production. Within the EU, products authorized for organic farming are listed in Annex II of the implementation rule 889/2008 (EC, 2008). Substances used for plant protection should be of plant, animal, microbial or mineral origin. Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and products produced from or by GMOs, as well as mineral nitrogen fertilizers are not allowed. Chemically synthesized products are only allowed if they are not available in sufficient quantities in their natural form (e.g. pheromones) and if conditions for their use do not result in contact of the product with the edible parts of the crop (e.g. application in dispensers).

IPM

IPM standards were developed and defined by the International Organisation for Biological and Integrated Control (IOBC) (Boller et al., 2004). With the Sustainable Use Directive (EC, 2009), IPM has become the main part of the European crop protection policy. Central goals of IPM are the prevention and suppression of harmful organisms, as well as the preference of non-chemical methods with few side effects on non-targets (Kogan, 1998). In addition, monitoring of pest insects, economic action thresholds and anti-resistance strategies are centrepieces of IPM strategies. Nevertheless, pest management in IPM is still dominated by the use of synthetic pesticides. In particular the strong focus on economic thresholds leads to a reductionist view of the systems (El-Wakeil, 2010). Environmental considerations and the presence or absence of beneficial insects are mostly not included in the economic thresholds (El-Wakeil, 2010). According to Ehler (2006), this perpetuates a ‘quick-fix mentality’, where symptoms are treated instead of causes. IPM principles are only reluctantly implemented by the farmers due to higher costs, and higher risk of failures of non-chemical control methods, as well as lack of experience with these methods (Gruys, 1982). Incentives for farmers to use alternative methods are missing, because the advantage of using sustainable and preventive measures ‘is at the social and environmental level and on the long-term, rather than at the private economic level and on the short-term’ (Gruys, 1982). In addition, the low price for synthetic pesticides does not reflect the true ecological costs. Thus, for the individual farmer it is often more economical to use a curative pesticide instead of preventive measures. The use of pesticides is more regulated in organic farming systems: only naturally derived substances are allowed. As availability and efficacy of these substances is limited and most of them are considerably more expensive than synthetic pesticides, organic farmers have a stronger incentive to consequently apply preventive measures.

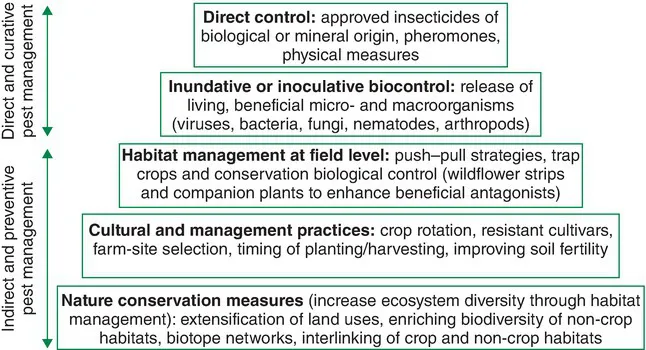

Conceptual Model for Pest Management in Organic Farming

A conceptual model for pest management in organic farming (Fig. 1.1) was proposed by Wyss et al. (2005), refined by Zehnder et al. (2007) and complemented by Luka (2012, cited in Forster et al., 2013). The fundamental first step of this holistic approach is the benefits of nature conservation measures: ecosystem diversity is increased through habitat management, extensification of land uses, establishment of non-crop habitats and biotope networks. The second step of the pyramidal model are cultural practices applied by the farmers in order to avoid pest damage (Peacock and Norton, 1990). These practices include crop rotation, increasing crop diversity, timely planting and harvesting, transplanting, weed management, choice of resistant varieties and avoiding areas with high pest presence on the farm level. These practices go hand in hand with the third step which is habitat management at the field level (i.e. companion plants, tailored wildflower strips, push–pull strategies) which aims at interlinking crop and non-crop habitats. These first three steps create a broad and solid basis for healthy plant development. Direct control methods based on biocontrol organisms or bioinsecticides are the fourth and fifth steps of the model. However, these methods can have side effects on beneficial arthropods and thus adversely affect ecosystem services needed for pest prevention. Thus, direct control measures should only be applied in case of threatening pest outbreaks and selective methods should be preferred. The use of non-selective biopesticides should be limited to a minimum. Within this chapter we will focus on the use of preventive strategies (the first three steps in the multi-level model). The last two steps (biocontrol and organically approved insecticides) are only briefly mentioned here and discussed in detail in Chapters 2 and 3 of this volume, respectively.

Nature Conservation Measures: the Basis for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

According to the Convention on Biological Diversity of Rio de Janeiro in 1992, biodiversity encompasses the variety of life on earth ranging from genes, through species, to entire ecosystems (United Nations, 1992). Ecosystem diversity covers the diversity of habitats or patches within a landscape and includes the diversity of farming systems, ratio of arable land to other land uses as well as interactions between agricultural land and nearby natural biotopes. Ecosystem diversity and diversified cropping systems have a range of benefits, both short term (e.g. by increase in crop yield and quality due to improved pest control) and long term (e.g. by re-establishing agroecosystem sustainability), on the agronomic level (e.g. biotic and abiotic stress resistance, production of cultivated ecosystems), as well as on the societal and ecological level (e.g. by landscape aesthetics, water and soil quality and flora and fauna conservation, including endangered species, existence of typical habitats with particular species) (Clergue et al., 2009; Malézieux et al., 2009).

Integrating biodiversity conservation into production systems

Agricultural ecosystems comprise productive areas (managed fields), as well as semi-natural and natural habitats (Moonen and Bàrberi, 2008). The productive areas can have a negative impact on biodiversity: monocultures treated with broad-spectrum pesticides to prevent pest outbreaks (Landis et al., 2000) decrease the natural enemies’ diversity, reduce species richness, abundance and effectiveness (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Winqvist et al., 2012). This can start a negative loop where the decrease in the natural enemy populations is followed by an increase in pest populations which necessitate an increase in pesticide applications, which once again negatively impact natural enemy populations (Sandhu et al., 2008; Geiger et al., 2010; Krauss et al., 2011). This negative loop, where practical protection of the rapeseed yield also ensures the highest possible pest population of Meligethes aeneus (Fabricius) for the next year, has been described by Hokkanen (2000). Contrary to productive areas, semi-natural and natural habitats are expected to have a positive impact on biodiversity which also benefit the productive areas, for example through biological control or pollination (Sandhu et al., 2008). The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (World Resources Institute, 2005) distinguishes the following ecosystem functions: (i) supporting services; (ii) provisioning services (e.g. food, pollination); (iii) regulating services (e.g. pest and disease control); and (vi) cultural services. The value of ecosystem services to agriculture is enormous and often underappreciated (Tscharntke et al., 2012; Power, 2014). The consequent use of functional agrobiodiversity might not only break the negative loop but even induce a positive loop (Krauss et al., 2011) where reduction of pesticides leads to an increase in antagonists which in turn leads to further reductions of pesticides.

However, there is still a debate how to integrate biodiversity conservation into production systems and how to best achie...