![]()

1 Ancient, Classical and Modern Biotechnology

The process of mankind’s development and food production has proceeded pari passu through the millennia. As Sauer pointed out, ‘man evolved with his food plants, forming a biological complex’, regardless of whether the man was a hunter-gatherer, a food-domesticator or a modern large-scale food manufacturer (Sauer, 1963, p. 155).

The first changes took place seamlessly, without increasing the food supply and without significant changes in the environment. An exception was the use and control of fire by early man, which caused the transformation of forest into grassland, permitted large migrations by enabling people to extend their ranges into habitats that were impossible to live in before, extended the period of activity independent of daylight, provided protection from predators and insects, and caused the evolution of man’s digestive system due to adjustments to cooked food. Wrangham et al. (1999, p. 573) assumed that cooking ‘doubled the energy value from carbohydrate in underground storage organs and increased it by 60% in seed.’

Animal and plant domestication had a special role in the further development of food production. Domestication can be defined as ‘a complex evolutionary process in which human use of plant and animal species leads to morphological and physiological changes that distinguish domesticated taxa from their wild ancestors’ (Purugganan and Fuller, 2009, p. 843). Domestication provided the impetus for humans to create a food surplus and build the world’s first villages and cities near fields of domesticated plants. Consequently, ‘this led to craft specializations, art, social hierarchies, writing, urbanization and the origin of the state’ (Purugganan and Fuller, 2009, p. 843).

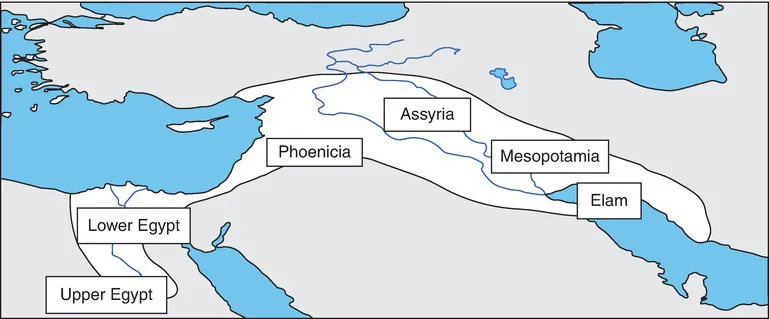

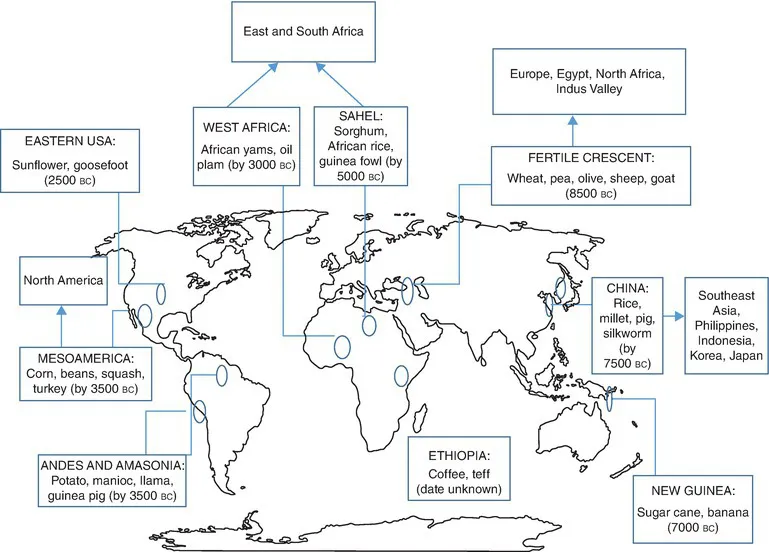

Many historians think domestication happened between 10,000 and 13,000 years ago. Numerous indications and evidence in the present suggest that the domestication of animals had to be preceded by the domestication of plants. Such examples can be found in the steppes of Iran and Afghanistan, or the Maasai ethnic group inhabiting southern Kenya and northern Tanzania who live in ways similar to man in the Neolithic period. There are numerous archaeological studies identifying the dynamics of domestication. The hunter-gatherer societies independently began food production in nine areas of the world: the Fertile Crescent (extending from the eastern Mediterranean upward through Anatolia and down into the valley of the Rivers Tigris and Euphrates) (Fig. 1.1), China, Mesopotamia, Andes/Amazonia, the American East, the Sahel, Tropical West Africa, Ethiopia and New Guinea (Fig. 1.2) (Diamond, 2002).

Eight plants are considered to be the domesticated ‘founder crops’: three cereals (einkorn wheat Triticum monococcum, emmer wheat Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum, and barley Hordeum vulgare), four pulses (lentil Lens culinaris, pea Pisum sativum, chickpea Cicer arietinum, and bitter vetch Vicia ervilia), and a single oil and fibre crop (flax Linum usitatissimum) (Weiss and Zohary, 2011). The origins of our modern wheat developed by cultivating its wild ancestors Triticum boeoticum and Triticum monococcum in the Karacadag mountain region (southeastern Turkey). Emmer wheat was also domesticated in the same region in Turkey, while the earliest barley (wild relative Hordeum spontaneum) is recorded in Syria. Syria was also an early home for lentils developed out of Lens c. orientalis and chickpeas. The first appearance of the domestic pea is in the Near East, while the earliest flax seeds came from Jericho. Not counting the domestic dog, it is believed that animal domestication started with sheep (Ovis aries), the first ‘meat’ animals adapted from different wild subspecies of Ovis gmelini (wild mouflon) in the Fertile Crescent; then most probably came goats (Capra hircus), from Capra aegargus (bezoar ibex wild goat) in Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and China (Luikart et al., 2001). Wild cattle (Bos primigenius) most likely had three main loci of domestication: the Taurus Mountains (Bos taurus), Indus Valley (Pakistan) (Bos indicus), and Algeria (Bos africanus) (Decker et al., 2014).

Agriculture was launched in the Fertile Crescent, the home of the most valuable crops and livestock, such as wheat, barley, peas, sheep, goats, cows and pigs. As can be seen in Fig. 1.2, the Fertile Crescent has the earliest dates of animal and plant local domestication (8500 BC), followed by China, New Guinea and the Sahel.

The earliest date of domestication recorded in the American East is 6000 years after the Fertile Crescent (2500 BC). From these centres, food production spread around the globe at different speeds, firstly at locations with similar climate and habitats, but ‘with the general axis oriented east–west for Eurasia and north–south for the Americas and Africa’ (Diamond, 2002, p. 703). The above does not mean that one can clearly delineate the period between hunter-gathering and farming, because there was and actually still is some overlap between them. Along with the hunter-gathering indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast living in a rich environment, the Apache also practised some farming. As Suttles (2009, p. 56) has suggested ‘․ ․ ․the Northwest Coast peoples seem to have attained the highest known levels of cultural complexity achieved on a food-gathering basis and among the highest known levels of population density. The Northwest Coast refutes many seemingly easy generalizations about people without horticulture or herds’. Knowledge about the existence of social inequality amongst the population that survived without animal and plant domestication could be considered as one of the most important advances in anthropological research in the last few decades (Sassaman, 2004).

If we exclude complex hunter-gatherer social formations that already practised sedentary or semi-sedentary lifestyles, nomadic hunter-gatherers started their sedentary lifestyle by applying farming practices to their permanent agricultural areas instead of migrating to follow the seasonal shifts in wild food:

The sedentary lifestyle permitted shorter birth intervals. Nomadic hunter-gatherers had previously spaced out birth intervals at four years or more, because a mother shifting camp can carry only one infant or slow toddler. . .Food production also led to an explosion of technology, because sedentary living permitted the accumulation of heavy technology (such as forges and printing presses) that nomadic hunter-gatherers could not carry, and because the storable food surpluses resulting from agriculture could be used to feed full-time craftspeople and inventors.

(Diamond, 2002, p. 703)

The advent of agriculture and, with it, of food surpluses, increased the density of population; caused epidemics of infectious diseases; led to social stratification, political centralization and the formation of standing armies; and led to nutritional changes and adaptation to a diet quite different from that of the hunter-gatherer: ‘a diet rich in simple carbohydrates, saturated fats and calories and salt, and lower in fibre, complex carbohydrates, calcium and unsaturated fats’ (Diamond, 2002, p. 704).

Unconscious selection of plants for desirable traits (around 9000 BC) resulted in the elimination of dormancy and seed dispersal, and actually led to dependable germination and the predictable continuity of plants in the field. Conscious plant cultivation for desirable traits started, also BC. Conscious cultivation led to the diversification of crops and their local adaptation, higher seed yield combined with a higher degree of self-pollination, and many other traits related to consumer acceptance, such as culinary preferences and quality processing. Domestication continued after the birth of Christ and is still going on; the only changing factor is the technology for obtaining the desired properties. As Darwin observed in 1868: ‘No doubt man selects varying individuals, sows their seeds, and again selects their varying offspring․ ․ ․Man therefore may be said to have been trying an experiment on a gigantic scale; and it is an experiment which nature during the long lapse of time has incessantly tried’ (Darwin, 2010, p. 2).

1.1 Historical Evolution of Biotechnology

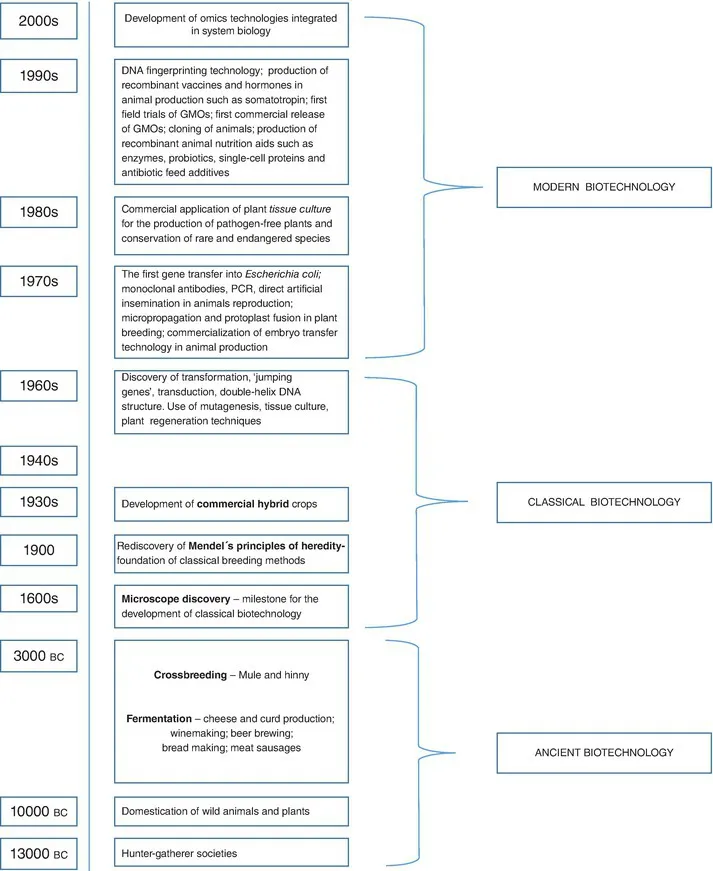

Among other things, domestication stimulated the magnification of food storage, a practice already followed in the pre-agricultural Near Eastern Early (14,500–12,800 cal BP) and Late Natufian periods (12,800–11,500 cal BP). Food storage coincided with the growth of microorganisms that caused the birth of the first biotech food applications – food fermentation. Fermentation can be defined as ‘the transformation of simple raw materials into a range of value-added products by utilizing the phenomenon of growth of microorganisms and/or their activities on various substrates’ (Prajapati and Nair, 2008, p. 2).

Fermentation is considered to be the world’s oldest food preservation method apart from the drying of food in the hot sun, with roots dating back deep into the past of the Middle East (Nummer, 2002). The first fermented products were created from stored milk surplus. The earliest evidence dates back as far as 7000 BC in the Fertile Crescent, and refers to cheese making. Archaeological records confirm the dates and origins of other fermented products as follows: winemaking process – Western Iran (6000 BC); wheat bread making – Egypt (3,500 BC); preparation of meat sausages – Babylonia (1,500 BC); sour rye breads – Europe (800 BC); preservation of vegetables – China (300 BC). Thanks to their understanding of how to use yeasts separated from wine to prepare bread, the Romans opened 250 bakeries around 100 BC. The oldest known (before 3000 BC) man-made animal ‘hybrid’ product of mating between two different species is the mule, a crossbreed between a male donkey and a female horse. A slightly less common ‘hybrid’, the hinny, was also bred in ancient times by the mating of a female donkey with a male horse. Highly valued in trade, the perdum-mule, a riding animal used mostly by kings, is found in Central Anatolia in the ancient town of Kaniš, and dates back to the 19th and 18th centuries BC (Michel, 2002).

Each of these ‘discoveries’ is accompanied by a legend. For example, it is believed that an Arabic trader accidentally discovered a way of making cheese. Preparing for a long journey through the desert, he put milk in a bag made of sheep stomach. Because of the rennet in the bag and the sun in the desert, the milk separated into curd and whey. Angels were said to have helped an ancient nomadic Turk prepare the first yoghurt, while the recipe for making kefir, which originates from the Caucasus Mountains, was kept secret for a long time because Mohammad strictly forbade transmitting it to people of faiths other than Islam. In the Old Testament, the mule replaced the donkey as the ‘royal beast’ and was ridden by King David and King Solomon at their coronations.

Leaving aside the legends and often accidental discoveries, it can be noticed that man travelled a long, gradual path from the hunter-gatherer to the modern producer dependent on technological innovation (Fig. 1.3).

The essential understanding of fermentation, which could not be performed without microorganisms, happened in the 17th century (around 1678), when Antony Van Leeuwenhoek developed his method of creating powerful lenses and applied them to the study of the microscopic world. The discovery of the microscope ‘was the milestone for the development of classical biotechnology’ (Pele and Cimpeanu, 2012, p. 6), and was a prerequisite for Louis Pasteur, in the middle of the 19th century, to do his great research into microbial fermentation, which revolutionized medicine, industry and agriculture.

The era of classical biotechnological evolution lasted until the 1970s. Although in 1665 the English scientist Robert Hooke had discovered cells while looking at a tiny slice of cork and van Leuwenhoek had discovered single-celled organisms in 1673 using a handmade microscope, further progress in cell investigation occurred alm...