- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Handbook of Equine Parasite Control

About this book

Handbook of Equine Parasite Control, Second Edition offers a thorough revision to this practical manual of parasitology in the horse. Incorporating new information and diagnostic knowledge throughout, it adds five new sections, new information on computer simulation methods, and new maps to show the spread of anthelmintic resistance. The book also features 30 new high-quality figures and expanded information on parasite occurrence and epidemiology, new diagnostics, treatment strategies, clinical significance of infections, anthelmintic resistance, and environmental persistence.

This second edition of Handbook of Equine Parasite Control brings together all the details needed to appropriately manage parasites in equine patients and support discussions between horse owners and their veterinarians. It offers comprehensive coverage of internal parasites and factors affecting their transmission; principles of equine parasite control; and diagnosis and assessment of parasitologic information. Additionally, the book provides numerous new case histories, covering egg count results from yearlings, peritonitis and parasites, confinement and deworming, quarantine advice, abdominal distress in a foal, and more.

- A clear and concise user-friendly guide to equine parasite control for veterinary practitioners and students

- Fully updated with new knowledge and diagnostic methods throughout

- Features brand new case studies

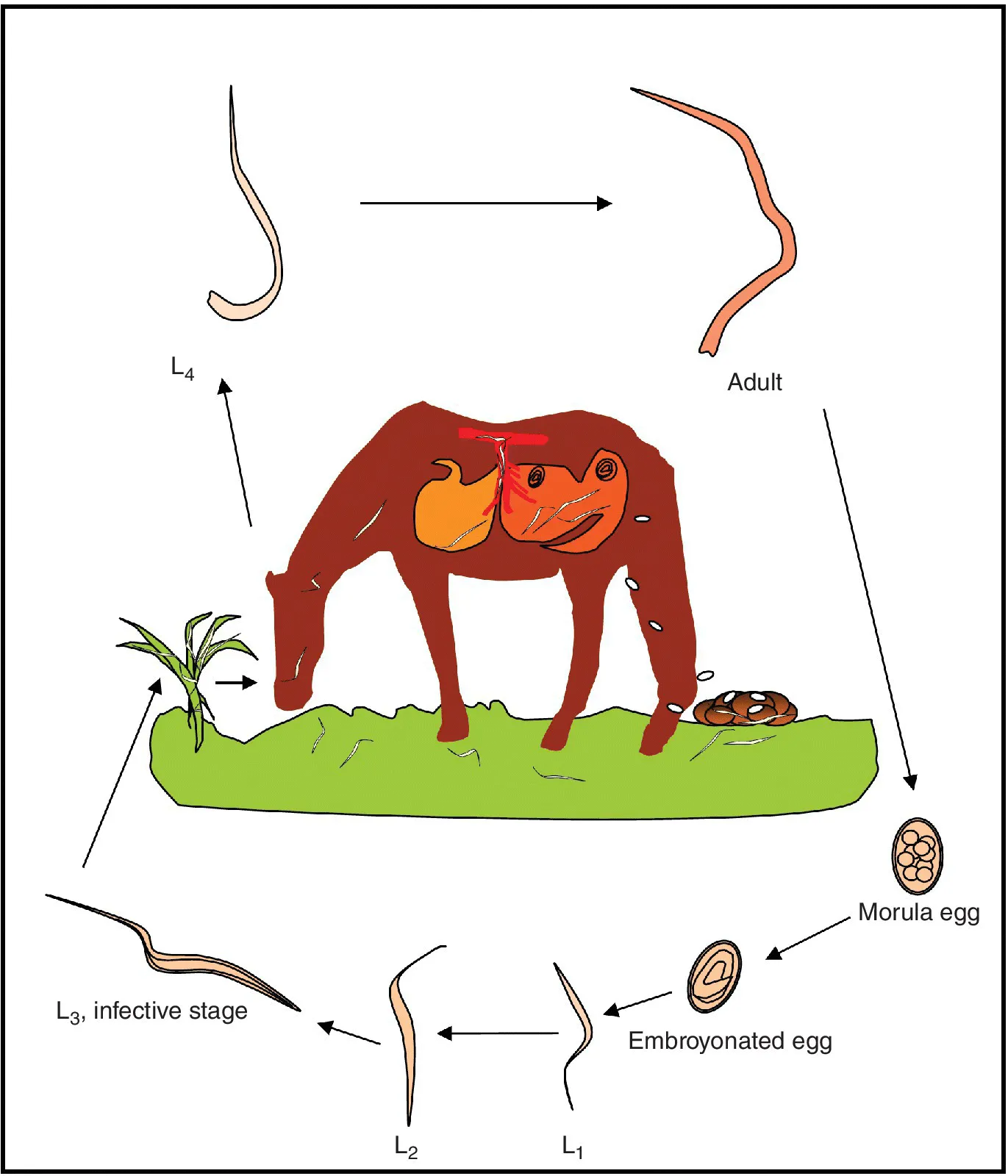

- Presents 30 new high-quality figures, including new life-cycle charts

- Provides maps to show the spread of anthelmintic resistance

Handbook of Equine Parasite Control is an essential guide for equine practitioners, veterinary students, and veterinary technicians dealing with parasites in the horse.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Section I

Internal Parasites and Factors Affecting Their Transmission

1

Biology and Life Cycles of Equine Parasites

Nematodes

Superfamily Strongyloidea

Strongylinae (large strongyles)

Strongylus vulgaris

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- Preface to the First Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgements

- Section I: Internal Parasites and Factors Affecting Their Transmission

- Section II: Principles of Equine Parasite Control

- Section III: Diagnosis and Assessment of Parasitologic Information

- Section IV: Case Histories

- Glossary

- Index

- End User License Agreement