- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

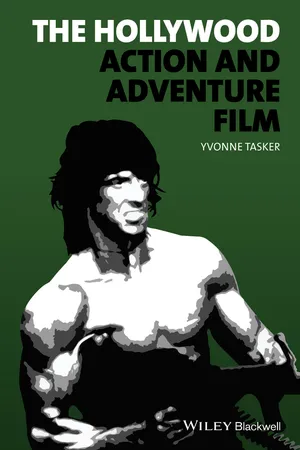

The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film

About this book

The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film presents a comprehensive overview and analysis of the history, myriad themes, and critical approaches to the action and adventure genre in American cinema.

- Draws on a wide range of examples, spanning the silent spectacles of early cinema to the iconic superheroes of 21st-century action films

- Features case studies revealing the genre's diverse roots – from westerns and war films, to crime and espionage movies

- Explores a rich variety of aesthetic and thematic concerns that have come to define the genre, touching on themes such as the outsider hero, violence and redemption, and adventure as escape from the mundane

- Integrates discussion of gender, race, ethnicity, and nationality alongside genre history

- Provides a timely and richly revealing portrait of a powerful cinematic genre that has increasingly come to dominate the American cinematic landscape

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film by Yvonne Tasker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

ACTION AND ADVENTURE AS GENRE

This book explores action and adventure as a mode of filmmaking and as a significant genre of American cinema. What we call “action” today has generic roots in a number of surprisingly diverse aspects of Hollywood cinema, from early chase films that crafted suspense to travel films that offered to audiences exotic and fantastic spectacles of other lands. Making sense of action involves taking account of these diverse origins; conversely, thinking about action as a genre allows us to see those origins in a different way.

Action is now a generic descriptor in its own right, one closely linked to adventure cinema; it is widely used to promote and distribute films in theatres and for home use. Yet, however familiar it may now be, this designation is relatively recent. Those earlier Hollywood genres that strongly emphasize action elements – including war movies, Westerns and thrillers – have their own distinct generic histories and conventions. It is not my intention here to suggest we think about all these movies as action, but rather to draw attention to action and adventure as long established features of Hollywood production as well as that of other national cinemas. In the process we will understand the longevity of action movies and how action emerges as a distinct genre during the “New Hollywood” of the 1970s, with its orientation around high concept, pre-sold blockbusters.

Associated with narratives of quest and discovery, and spectacular scenes of combat, violence and pursuit, action and adventure films have been produced throughout Hollywood’s history. They are not restricted to any particular historical or geographic setting (which provided the basis for early iconographic models of genre). Indeed, the basic elements of physical conflict, chase and challenge can be inflected in any number of different directions. Action can be comic, graphically violent, fantastic, apocalyptic, military, conspiratorial and even romantic.

Action and adventure cinemas thus pose something of a challenge to genre theory as it has developed within film studies. Despite the recognizability of particular action or adventure cycles – Warner Bros. historical adventures of the 1930s, say, or the bi-racial cop movies of the 1980s – the genre has no clear and consistent iconography or setting. There are some broadly consistent and identifiable themes underpinning action: these include the quest for freedom from oppression, say, or the hero’s ability to use his/her body in overcoming enemies and obstacles. And physical conflicts or challenge, whether battling human or alien opponents or even hostile natural environments, are fundamental to the genre in all its manifestations. Yet the very diversity of action and adventure requires thinking about genre in a different way than the familiar analyses of more clearly defined genres such as the Western, which has been fruitfully explored in terms of its rendition of themes to do with the symbolic opposition of wilderness and civilization, nature and culture (Kitzes, 1969).

Adopting a genre-based approach to action doesn’t mean reducing this diversity to a set formula: as if Star Wars (1977) were the same as Die Hard (1988), or Strange Days (1995) the same as Speed (1994). Action and adventure as cinematic forms are manifest in a multiplicity of different genres and sub-genres that develop and change over time. As such, action and adventure provides a useful way into ongoing debates regarding the instability of genre and the extent to which individual films can be regarded as participating simultaneously in a number of genres. So, to take these examples, we might agree that Die Hard is quite different from Star Wars, but note that both Star Wars and Strange Days make use of science-fiction conventions. Yet these two films do so in very different ways – notably in the presentation of violence – and in combination with other generic elements.

Star Wars exemplifies a resurgent adventure strand of the 1970s cinema, its Jedi knights and light sabers, as well as set-piece scenes such as characters swinging on ropes between platforms, recalling the swordfights of swashbuckling films. Star Wars also deploys western iconography via (admittedly alien) desert landscapes and in particular through Han Solo (Harrison Ford)’s costume and mannerisms. All this takes place in juxtaposition with the sort of science fiction evoked by the imagery of space travel as routine and spectacular space battles. Star Wars places its futuristic scenario in relation to genres defined by their pastness: “a long time ago…” Strange Days, by contrast, is set in the near future (now the past) of 1999. It employs intense mobile camerawork to evoke chase and pursuit in its action sequences. The futuristic technology portrayed is to do with vision and the recording of experiences; the film uses salacious imagery alongside its conspiratorial thriller and film noir elements. While both movies can be situated as part of action and adventure traditions, understanding the diversity of filmmaking styles is important to analyzing the genre.

Given action’s diverse history and its complex relationship to other genres, such as the Western or science-fiction, this book considers action both as an overarching term and in relation to a series of sub-genres. This chapter gives an overview of some of the main ways in which genre has been theorized in film studies and asks about how these different approaches might help in thinking about action and adventure. Since “action” per se has not been central to genre theory, this involves acknowledging the specific context used by critics (e.g., Bazin on the Western) while summarizing the relevance of these debates for an understanding of action as genre.

Theories of Genre: Author, Icon and Industry

The development of genre criticism represented a crucial stage in the emergence of film studies as a discipline and was particularly important in its attempt to engage with popular and especially Hollywood cinema during the 1950s and 1960s. Given the typically low critical status accorded to action and adventure movies (a few notable exceptions aside) this is also a particularly important context for the subsequent emergence of scholarship around the genre. Seminal essays published in the 1940s and 1950s by French critic André Bazin and American writer Robert Warshow developed interest in genre via evocative accounts of the cultural work and relevance of the Western and the gangster film, both action-oriented genres.

These early essays are intriguing since they foreground the cultural significance of these genres, largely in terms of the assumed connections between genre filmmaking and myth. Thus, Bazin regards the Western as exemplifying American film in articulating values to do with “establishing justice and respect for the law” (1995: 145). For Warshow, the gangster film is significant not for any relation to social reality but as an aesthetic experience that speaks against what he regards as the compulsory optimism of American life: “the gangster speaks for us, expressing that part of the American psyche which rejects the qualities and the demands of modern life, which rejects ‘Americanism’ itself” (1964: 86). Approaching Hollywood films for what they can tell us about social values and systems of meaning – that is, myth and ideology – has proved central to writings on action. Indeed until relatively recently, an interest in the ideology of action has tended to be at the cost of more sustained discussion of the formal elements that make the genre so distinctive and, arguably, popular.

For Bazin the distinctive achievement of the Western lies not in action elements, though he acknowledges their importance, but in its articulation of myth. Thus he writes:

It is easy to say that because the cinema is movement the western is cinema par excellence. It is true that galloping horses and fights are its usual ingredients. But in that case the western would simply be one variety of adventure story.(1995: 141)

Here, Bazin asserts unequivocally that the Western’s significance lies not in its dynamic visual elements or in its adventure-driven narratives. Chapter 3 addresses in more detail the different ways in which critics have explored both the ideological work and, latterly, aesthetic aspects of action and adventure cinema. Here, we can note a persistent feature of criticism surrounding action genres; an ambivalence about cultural value. While across decades critics have understood the exhilarating properties of action, disagreements proceed from what significance (and what value) should be accorded to such cinematic sensuality. For Brian Taves, for example, adventure cinema is “something beyond action,” elevated “beyond the physical challenge” by “its moral and intellectual flavour.” (1993: 12). By implication action is crude, a framework that requires gifted filmmakers and performers to transcend its conventions. Indeed for those writers, such as Wheeler Winston Dixon, who regret “the paucity of imagination and/or risk in Hollywood cinema,” (1998: 182) action is among the forms of mega-budget, effects-heavy filmmaking that has come to symbolize what they regard as a loss of meaning and complexity.

By contrast, Warshow writes that “the gangster film is simply one example of the movies’ constant tendency to create fixed dramatic patterns that can be repeated indefinitely with a reasonable expectation of profit,” while being clear that this “rigidity is not necessarily opposed to the requirements of art.” (1964: 85). Indeed thinking about genre, with its emphasis on formulae and repetition, has encouraged film scholars to give more attention to the commercial and institutional aspects of film production. Whether the focus is industry or aesthetics, critics tend to agree that genre is distinguished by patterns of repetition and difference. Thus genre critics are interested in the visual, narrative and thematic patterns that recur over time as well as taking account of the ways in which film texts vary those patterns.

Iconographic models of genre emphasized the continuity provided by recurrent scenes and signs. Colin McArthur’s well-known work on the gangster film foregrounds (1972) processes whereby repetition generates familiarity, but just as importantly allows objects and actions to accrue meaning through that very repetition. So, for instance, genre critics have noted the resonance and meaning of signs such as landscape, horses and guns in the Western. For action the key sign is the movement of the body through space; the body is central to action whether it is superhuman or simply enhanced. Heroic bodies both withstand and inflict violence. They are juxtaposed with an iconography of violence stemming from the weapon as accessory. Both the action body and action spectacle is characterized by movement: from the lengthy depictions of pursuit and combat to the explosions that feature so prominently in action spectacle. Explosions are a generic expectation of action turning on the movement of billowing flames and of the objects thrown up or buildings imploded by the blast. The familiar action image of the hero’s body propelled by a blast effectively couples both forms of movement, his/her survival underlining their strength and suitability for violence.

Of course as noted earlier, action and adventure are broad descriptors when set against even a genre as expansive as the Western. Eric Lichtenfeld rightly draws attention to the fascination with weaponry that characterizes gunplay-heavy contemporary Hollywood action, for instance, suggesting that an “enthusiasm for action film modernity” in John Wayne’s McQ (1974) is typified by a “zeal for weaponry.” (2004: 31) Modern Hollywood action and adventure is as likely to suggest a fascination at work with the body as a weapon – in part a consequ...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- LIST OF PLATES

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHAPTER 1: ACTION AND ADVENTURE AS GENRE

- CHAPTER 2: ACTION AND ADVENTURE: HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL OVERVIEW

- CHAPTER 3: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON ACTION AND ADVENTURE

- CHAPTER 4: SILENT SPECTACLE AND CLASSICAL ADVENTURE: THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (1924) AND THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (1938)

- CHAPTER 5: WAR, VIOLENCE AND THE AMERICAN ACTION HERO: SANDS OF IWO JIMA (1949) AND HELL IS FOR HEROES (1962)

- CHAPTER 6: VIOLENCE AND URBAN ACTION: DIRTY HARRY (1971)

- CHAPTER 7: NOSTALGIC ADVENTURE AND RECYCLED CULTURE: RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (1981) AND PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN (2003)

- CHAPTER 8: ACTION BLOCKBUSTERS IN THE 1980S: RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II (1985) AND DIE HARD (1988)

- CHAPTER 9: GLOBAL AND POSTMODERN ACTION: CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (2000) AND KILL BILL (2003)

- CHAPTER 10: ESPIONAGE ACTION: THE BOURNE IDENTITY (2002) AND SALT (2010)

- CHAPTER 11: SUPERHERO ACTION CINEMA: X-MEN (2000) AND THE AVENGERS (2012)

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT