- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of Greece, 1300 to 30 BC

About this book

A History of Greece: 1300?30 BC, offers a comprehensive introduction to the foundational political history of Greece, from the late Mycenaean Age through to the death of Cleopatra VII, the last Hellenistic monarch of Egypt.

- Introduces textual and archaeological evidence used by historians to reconstruct historical events during Greece's Bronze, Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods

- Reveals the political and social structure of the Greek world in the late Mycenaean period (thirteenth century BC) through analysis of the Linear B tablets, the oldest surviving records in Greek

- Features numerous references to original source materials, including various fragmentary papyri, inscriptions, coins, and other literary sources

- Provides extensive coverage of the Hellenistic period, and covers areas excluded from most Greek history texts, including the Greek West

- Features judicious use of illustrations throughout, and considers instructors' teaching needs by structuring the later sections to facilitate teaching a parallel course in Roman History

- Balances scholarship with a reader-friendly approach to create an accessible introduction to the political history of one of most remarkable ancient civilizations and sophisticated periods of world history

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of Greece, 1300 to 30 BC by Victor Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Geography of Greece

Introduction

All history takes place within a geographical setting. It is not merely a matter of needing to know where places are in order to follow an historical narrative, but also one of understanding why over time certain recognizable patterns emerge and why the people who settle in a given region tend to develop in one way instead of in another. After general sections on the topography, climate, and use of the land overall, this chapter will present a tour of the Greek world to show how the specific geography of the major regions helped shape their historical development. The aim is to explain some of the “givens” in Greek history: why the Thessalians had the best horses and consequently the first cavalry in Greece; why the Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor had more to do with mainland Greece than with the regions to the east; why most sea traffic from west to east passed over the Isthmus instead of around the Peloponnese, such that Sparta lay off the beaten track while Corinth on the Isthmus grew prosperous; and so on. The chapter serves both as an introduction to the narrative that follows, with references ahead to the relevant chapters, and also as a resource for consultation when appropriate.

General Topography

Greece lies at the base of the Balkan Peninsula in southern Europe. It juts out into the Mediterranean Sea between the Adriatic on its west and the Aegean on its east. Greece is a mountainous land, and the mountain ranges as a general rule run from northwest to southeast. They become progressively lower farther to the south and eventually dip below sea level. Their highest peaks, however, often still rise above sea level to form islands. Thus, the same geological formation which makes up Magnesia drops below sea level south of Cape Sepias before it again rises above the sea in the form of the island of Euboea. South of Carystus it drops again, but its highest peaks farther south appear as the islands of Andros and Tenos.

During unsettled times, the mountain ranges can direct the flow of migrations (see chap. 3) through the land: such migrations have tended to follow the ranges' northwest–southeast orientation southwards until reaching either a west–east pass (at which point the migrating peoples could turn left and proceed farther in an easterly direction) or an inlet of the sea (which the migrating peoples could then cross on makeshift boats). In settled times, the mountains can help divide the country into sections for human habitation, sections which can be identical with communities' territories: this is especially true for cities in mountain valleys (e.g., Tegea and Mantinea in Arcadia) or on small coastal plains (e.g., Troezen or Epidaurus in the Argolis). The mountainous nature of the country also means that fertile plains are few; but where such plains do exist, they tend to be intensely cultivated. The mountains also mark the coastline which, owing to the ruggedness and unevenness of the land, has thousands of inlets and gulfs. The largest of these is the Gulf of Corinth which, together with the Saronic Gulf, almost divides Greece in two; the land to the south of these two gulfs, the Peloponnese, is connected only by a narrow isthmus to the rest of Greece (see Figure 1.1). That isthmus – always known simply as “the Isthmus” – had importance both for land and sea traffic. All land travel between the Peloponnese and the rest of Greece had to pass across it. At the same time, it proved easier and quicker in antiquity for those transporting goods from west to east by sea to unload the goods at the Isthmus, to haul them across, and then to reload them on the other side (see also Box 1.1). The Isthmus, then, functioned as an important connecting point for sea travel as well.

Figure 1.1 Satellite image of the Isthmus. Source: Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, NASA-Johnson Space Center. “The Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth.” <http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/scripts/sseop/QuickView.pl?directory=ESC&ID=ISS023-E-5385>01/10/2013 10:52:32

Given the mountainous nature of the land, which tended to impede travel overland, much travel was in fact by sea; and the sea usually helped unite rather than divide Greece. This was especially true for the Aegean Sea. Islands dot the sea such that when sailing from mainland Greece to Asia Minor one never loses sight of land – from any one island the next is always visible. In effect, the islands function as stations on a road across the water.

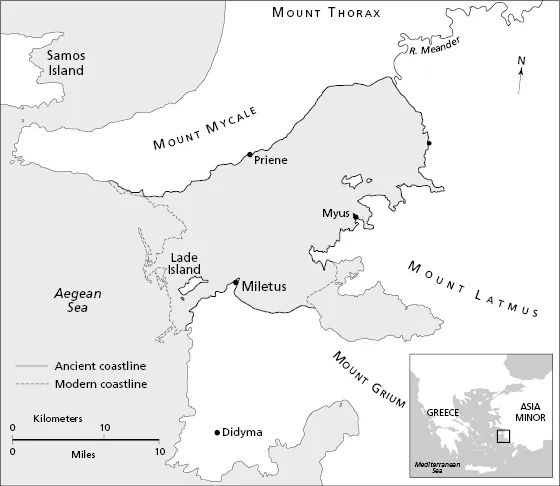

As one moves farther east across the Aegean, one eventually reaches the mainland of Asia Minor. In this region Greeks settled in the eleventh to tenth centuries bc. (see chap. 3). They came from the West, moving across the water island by island. For this reason their settlements in Asia Minor tended to look westwards to the sea rather than farther inland. When the Persians in the early fifth century again took possession of those Greek cities which had risen up in the Ionian Revolt (see chap. 9), the Persians sent their fleet along the coast from city to city because the cities were far more easily accessible by sea than by land. Miletus, in the classical period the most important Greek settlement on the mainland in Asia Minor, provides a spectacular example of this orientation towards the sea. Although the city is technically on the mainland, mountains to the south make it almost inaccessible by land (see Figure 1.2). The simplest way to travel from Miletus into the interior of Asia Minor was actually to embark on a ship, to sail across an inlet of the sea, and then to disembark in the plain of the Meander River. From here one could easily journey overland into the interior.

Figure 1.2 Position of Miletus on Gulf of Meander River in ancient times

Box 1.1 Mt. Athos and Other Coastlines Exposed to the Aegean

The prevailing weather patterns in the Aegean – in particular harsh storms from the east especially during the winter – combine with the geology of mainland Greece to create an unusual feature of its eastern coastline. The storms erode the land until they reach the hard bedrock of the mountains. The resulting coastline consists of steep, rugged cliffs with few harbors or safe anchorages. Wherever a mountain is directly exposed to the storms – Mt. Athos (see Figure 1.3), Magnesia, the island of Euboea, Cape Malea – such a coastline arises. But any body of water behind the exposed mountain – for example, the strait between Euboea and the mainland – remains calm with a gentle coastline replete with harbors on both sides. Thus, ships sailing northward from Attica kept to the west of Euboea. In the south, Cape Malea (see Figure 1.4) proved so prone to storms and so dangerous for mariners that circumnavigation of the Peloponnese rarely took place (major naval expeditions were the one exception). Hence, traffic west from the Aegean passed over the Isthmus and through the Gulf of Corinth.

Figure 1.3 The exposed eastern side of Mt. Athos. Source: Gabriel, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mount_Athos_by_cod_gabriel_20.webp (accessed 10th January 2013). CC BY 2.0

Figure 1.4 Satellite image of Cape Malea. Source: Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, NASA-Johnson Space Center. “The Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth.” <http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/scripts/sseop/QuickView.pl?directory=ESC&ID=ISS015-E-9024>01/10/2013 12:17:06

Greeks reached the northern coast of the Aegean by sea as well – though a little later this time, as late as the eighth century; and while expansion into the interior here did take place (especially on account of the silver and gold mines of Pangaeum), the same more or less held true here as for the settlements in Asia Minor – they looked towards mainland Greece with which they were connected by the Aegean Sea. In every respect the Aegean united Greeks; and the region around the Aegean always formed the core territory of Greek civilization.

Another basic fact about Greece requires a brief comment at the end of this section. Greece lies close to where the Eurasian and African tectonic plates meet, and there is much seismic activity. Earthquakes and tsunamis are common and occasionally devastating. Portions of the land, moreover, are of volcanic origin – the island of Thera, with its active volcano which during the Bronze Age (around the middle of the second millennium bc) erupted cataclysmically, is only the best known.

Climate

Greece is a hot, thirsty land. Most rivers are dry through the summer as evaporation proceeds more quickly than springs or rainfall can replenish the water. The rainy season begins in the late autumn, around November. With the rains, torrents rush down ravines and the dry beds of rivers are filled again.

The mountain ranges divide Greece up into countless “compartments,” each with its own microclimate determined by whether the mountains shield it from rain or trap rain in it; by whether it is exposed or closed to breezes off the Aegean; and by whether it is protected from or open to storms. Despite the overall aridity of much of the land, pockets (such as the plain near the head of the Argolic Gulf) are moisture-laden or even swampy (for example, the land at the head of the Messenian Gulf). In such regions even water-intensive crops, such as flax in Messenia, can be planted; orange and lemon groves today cover the plain of Argos near the sea. The general paucity of water, however, means that the staple grain in Greece tends to be the less nutritious barley that grows in lower-quality soil and requires less water; only in a few regions, like the plain of Eleusis, can the more nutritious wheat be planted.

Towards the south the temperature, even during the winter, remains fairly warm. In the north, however, the winters can be bitterly cold. The severity of the winter can also vary a great deal according to altitude, with the lower regions having considerably warmer weather. Although one can make some generalizations, where climate is concerned, every region in Greece is unique.

The Use of the Land

The climate and the topography work together to affect how humans use the land. First, crops are planted during the winter – only then is there sufficient water –, and the harvest takes place in the early spring. This agricultural cycle, incidentally, dictated the military season in antiquity: over the winter men stayed home and farmed; only after they had gathered in the harvest could they go out to war. Summer, then, was the time for warfare. The storms which brought the rain also made the winter unsafe for sailing so naval campaigns were confined to the summer as well.

Second, because mountains make a large percentage of the land unusable for humans, the remaining land was intensely worked to best effect. First-rate land tended to be reserved for staple grains, whi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Blackwell History of the Ancient World

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Figures

- Tables

- Boxes

- Abbreviations and Reference Conventions

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1: The Geography of Greece

- Part I: Bronze and “Dark Age”: circa 1300–800 bc

- Part II: The Archaic Period: circa 800–479 bc

- Part III: The Classical Period: 479–323 bc

- Part IV: The Hellenistic Period: 323–30 bc

- Tables of Rulers

- Glossary

- Index