- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Green Biocatalysis

About this book

Green Biocatalysis presents an exciting green technology that uses mild and safe processes with high regioselectivity and enantioselectivity. Bioprocesses are carried out under ambient temperature and atmospheric pressure in aqueous conditions that do not require any protection and deprotection steps to shorten the synthetic process, offering waste prevention and using renewable resources.

Drawing on the knowledge of over 70 internationally renowned experts in the field of biotechnology, Green Biocatalysis discusses a variety of case studies with emphases on process R&D and scale-up of enzymatic processes to catalyze different types of reactions. Random and directed evolution under process conditions to generate novel highly stable and active enzymes is described at length. This book features:

- A comprehensive review of green bioprocesses and application of enzymes in preparation of key compounds for pharmaceutical, fine chemical, agrochemical, cosmetic, flavor, and fragrance industries using diverse enzymatic reactions

- Discussion of the development of efficient and stable novel biocatalysts under process conditions by random and directed evolution and their applications for the development of environmentally friendly, efficient, economical, and sustainable green processes to get desired products in high yields and enantiopurity

- The most recent technological advances in enzymatic and microbial transformations and cuttingedge topics such as directed evolution by gene shuffling and enzyme engineering to improve biocatalysts

With over 3000 references and 800 figures, tables, equations, and drawings, Green Biocatalysis is an excellent resource for biochemists, organic chemists, medicinal chemists, chemical engineers, microbiologists, pharmaceutical chemists, and undergraduate and graduate students in the aforementioned disciplines.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Biocatalysis and Green Chemistry

1.1 INTRODUCTION TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND GREEN CHEMISTRY

Green chemistry efficiently utilizes (preferably renewable) raw materials, eliminates waste and avoids the use of toxic and/or hazardous reagents and solvents in the manufacture and application of chemical products.

- Waste prevention instead of remediation

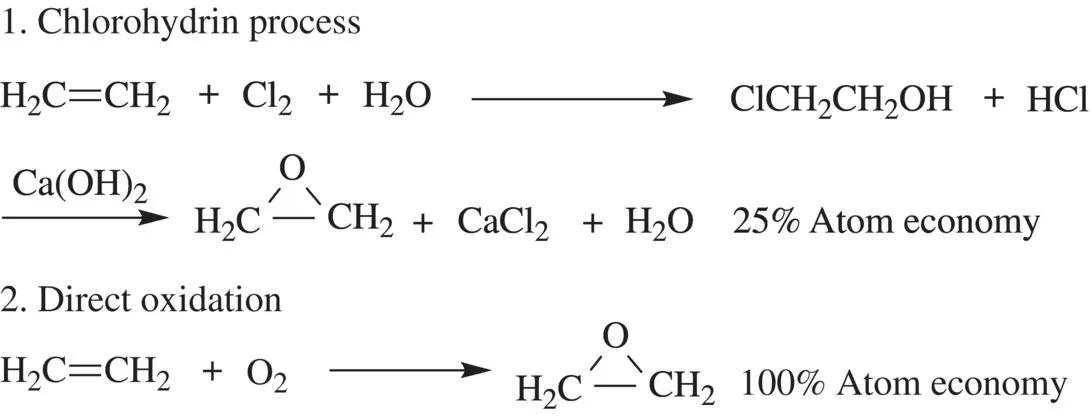

- Atom efficiency

- Less hazardous materials

- Safer products by design

- Innocuous solvents and auxiliaries

- Energy efficient by design

- Preferably renewable raw materials

- Shorter synthesis (avoid derivatization)

- Catalytic rather than stoichiometric reagents

- Design products for degradation

- Analytical methodologies for pollution prevention

- Inherently safer processes

1.2 GREEN CHEMISTRY METRICS

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- About the Editor

- Contributors

- CHAPTER 1: Biocatalysis and Green Chemistry

- CHAPTER 2: Enzymatic Synthesis of Chiral Amines using ω-Transaminases, Amine Oxidases, and the Berberine Bridge Enzyme

- CHAPTER 3: Decarboxylation and Racemization of Unnatural Compounds using Artificial Enzymes Derived from Arylmalonate Decarboxylase

- CHAPTER 4: Green Processes for the Synthesis of Chiral Intermediates for the Development of Drugs

- CHAPTER 5: Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of Alcohols, Amines, and Amino Acids

- CHAPTER 6: Recent Developments in Flavin-Based Catalysis

- CHAPTER 7: Development of Chemoenzymatic Processes

- CHAPTER 8: Epoxide Hydrolases and their Application in Organic Synthesis

- CHAPTER 9: Enantioselective Acylation of Alcohol and Amine Reactions in Organic Synthesis

- CHAPTER 10: Recent Advances in Enzyme-Catalyzed Aldol Addition Reactions

- CHAPTER 11: Enzymatic Asymmetric Reduction of Carbonyl Compounds

- CHAPTER 12: Nitrile-Converting Enzymes and their Synthetic Applications

- CHAPTER 13: Biocatalytic Epoxidation for Green Synthesis

- CHAPTER 14: Dynamic Kinetic Resolution via Hydrolase–Metal Combo Catalysis

- CHAPTER 15: Discovery and Engineering of Enzymes for Peptide Synthesis and Activation

- CHAPTER 16: Biocatalysis for Drug Discovery and Development

- CHAPTER 17: Application of Aromatic Hydrocarbon Dioxygenases

- CHAPTER 18: Ene-reductases and their Applications

- CHAPTER 19: Recent Developments in Aminopeptidases, Racemases, and Oxidases

- CHAPTER 20: Biocatalytic Cascades for API Synthesis

- CHAPTER 21: Yeast-Mediated Stereoselective Synthesis

- CHAPTER 22: Biocatalytic Introduction of Chiral Hydroxy Groups using Oxygenases and Hydratases

- CHAPTER 23: Asymmetric Synthesis with Recombinant Whole-Cell Catalysts

- CHAPTER 24: Lipases and Esterases as User-Friendly Biocatalysts in Natural Product Synthesis

- CHAPTER 25: Hydroxynitrile Lyases for Biocatalytic Synthesis of Chiral Cyanohydrins

- CHAPTER 26: Biocatalysis

- CHAPTER 27: Biotechnology for the Production of Chemicals, Intermediates, and Pharmaceutical Ingredients

- CHAPTER 28: Microbial Transformations of Pentacyclic Triterpenes

- CHAPTER 29: Transaminases and their Applications

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app