![]()

Part One

Data Sources

![]()

1

Protein Structural Databases in Drug Discovery

Esther Kellenberger and Didier Rognan

1.1 The Protein Data Bank: The Unique Public Archive of Protein Structures

1.1.1 History and Background: A Wealthy Resource for Structure-Based Computer-Aided Drug Design

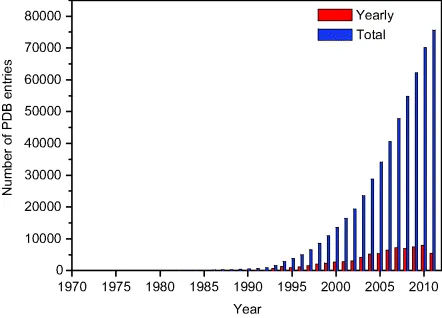

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) was founded in the early 1970s to provide a repository of three-dimensional (3D) structures of biological macromolecules. Since then, scientists from around the world submit coordinates and information to mirror sites in the Unites States, Europe, and Asia. In 2003, the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB, USA), the Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe) – the Macromolecular Structure Database at the European Bioinformatics Institute (MSD-EBI) before 2009, and the Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj) at the Osaka University formally merged into a single standardized archive, named the worldwide PDB (wwPDB, http://www.wwpdb.org/) [1]. At its creation in 1971 at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, the PDB registered seven structures. With more than 75 000 entries in 2011, the number of structures being deposited each year in PDB has been constantly increasing (Figure 1.1).

The growth rate was especially boosted in the 2000s by structural genomics initiatives [2,3]. Research centers from around the globe made joint efforts to overexpress, crystallize, and solve the protein structures at a high throughput for a reduced cost. Particular attention was paid to the quality and the utility of the structures, thereby resulting in supplementation of the PDB with new folds (i.e., three-dimensional organization of secondary structures) and new functional families [4,5].

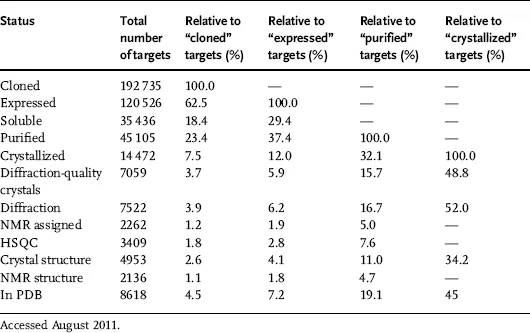

The TargetTrack archive (http://sbkb.org) registers the status of macromolecules currently under investigation by all contributing centers (Table 1.1) and illustrates the difficulty in getting high-resolution crystal structures, since only 5% targets undergo the multistep process from cloning to deposition in the PDB.

Table 1.1 TargetTrack status statistics

If only 450 complexes between an FDA-approved drug and a relevant target are available according to the DrugBank [6], the PDB provides structural information for a wealth of potential druggable proteins, with more than 40 000 different sequences that cover about 18 000 clusters of similar sequences (more than 30% identity).

1.1.2 Content, Format, and Quality of Data: Pitfalls and Challenges When Using PDB Files

1.1.2.1 The Content

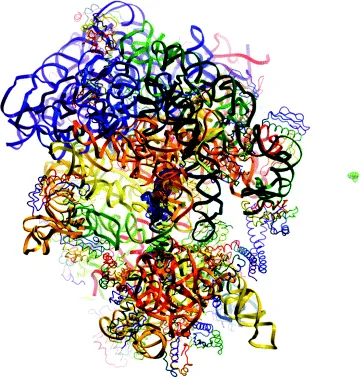

The PDB stores 3D structures of biological macromolecules, mainly proteins (about 92% of the database), nucleic acids, or complexes between proteins and nucleic acids. The PDB depositions are restricted to coordinates that are obtained using experimental data. More than 87% of PDB entries are determined by X-ray diffraction. About 12% of the structures have been computed from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements. Few hundreds of structures were built from electron microscopy data. The purely theoretical models, such as ab initio or homology models, are no more accepted since 2006. For most entries, the PDB provides access to the original biophysical data, structure factors and restraints files for X-ray and NMR structures, respectively. During the past two decades, advances in experimental devices and computational methods have considerably improved the quality of acquired data and have allowed characterization of large and complex biological specimens [7,8]. As an example, the largest set of coordinates in the PDB describes a bacterial ribosomal termination complex (Figure 1.2) [9]. Its structure determined by electron microscopy includes 45 chains of proteins and nucleic acids for a total molecular weight exceeding 2 million Da.

To stress the quality issue, one can note the recent increase in the number of crystal structures solved at very high resolution: 90% of the 438 structures with a resolution better than 1 Å was deposited after year 2000. More generally, the enhancement in the structure accuracy translates into a more precise representation of the biopolymer details (e.g., alternative conformations of an amino acid side chain) and into the enlarged description of the molecular environment of the biopolymer, that is, of the nonbiopolymer molecules, also named ligands. Ligands can be any component of the crystallization solution (ions, buffers, detergents, crystallization agents, etc.), but it can also be biologically relevant molecules (cofactors and prosthetic groups, inhibitors, allosteric modulators, and drugs). Approximately 11 000 different free ligands are spread across 70% of the PDB files.

1.1.2.2 The Format

The conception of a standardized representation of structural data was a requisite of the database creation. The PDB format was thus born in the 1970s and was designed as a human-readable format. Initially based on the 80 columns of a punch card, it has not much evolved over time and still consists in a flat file divided into two sections organized into labeled fields (see the latest PDB file format definition at http://www.wwpdb.org/docs.html). The first section, or header, is dedicated to the technical description and the annotation (e.g., authors, citation, biopolymer name, and sequence). The second one contains the coordinates of biopolymer atoms (ATOM records), the coordinates of ligand atoms (HETATM records), and the bonds within atoms (CONECT records). The PDB format is roughly similar to the connection table of MOL and SD files [10], but with an incomplete description of the molecular structure. In practice, no information is provided in the CONECT records for atomic bonds within biopolymer residues. Bond orders in ligands (simple, double, triple, and aromatic) are not specified and the connectivity data may be missing or wrong. In the HETATM records, each atom is defined by an arbitrary name and an atomic element (as in the periodic table). Because the hydrogen atoms are usually not represented in crystal structures, there are often atomic valence ambiguities in the structure of ligands.

To overcome limits in data handling and storage capacity for very large biological molecules, two new formats were introduced in 1997 (the macromolecular crystallographic information file or mmCIF) and 2005 [the PDB markup language (PDBML), an XML format derivative] [11,12]. They better suit the description of ligands, but are however not widely used by the scientific community. There are actually few programs able to read mmCIF and PDBML formats, whereas almost all programs can display molecules from PDB input coordinates.

1.1.2.3 The Quality and Uniformity of Data

Errors and inconsistencies are still frequent in PDB data (see examples in Table 1.2). Some of them are due to evolution in time of collection, curation, and processing of the data [13]. Others are directly introduced by the depositors because of the limits in experimental methods or because of an incomplete knowledge of the chemistry and/or biology of the studied sample. In 2007, the wwPDB released a complete remediated archive [14]. In practice, sequence database references and taxonomies were updated and primary citations were verified. Significant efforts have also been devoted to chemical description and nomenclature of the biopolymers and ligands. The PDB file format was upgraded (v3.0) to integrate uniformity and remediation data and a reference dictionary called the Chemical Component Dictionary has been established to provide an accurate description of all the molecular entities found in the database. To date, however, only a few modeling programs (e.g., MOE1 and SYBYL2) make use of the dictionary to complement the ligand information encoded in PDB files.

Table 1.2 Common errors in PDB files and effect of the wwPDB remediation

| Invalid source organism | Annotation | Fixed |

| Invalid reference to protein sequence databases | Annotation | Fixed |

| Inconsistencies in protein sequencesa | Annotation | Fixed |

| Violation of nomenclature in proteinb | Structure | Fixed |

| Incomplete CONECT record for ligand residues | Structure | Partly solved |

| Wrong chemistry in ligand residues | Structure | Partly solved |

| Violation of nomenclature in ligandc | Structure | Unfixed |

| Wrong coordinatesd | Structure | Unfixed |

The remediation by the wwPDB yielded in March 2009 to the version 3.2 of the PDB archive, with a focus on detailed chemistry of biopolymers and bound ligands. Remediation is still ongoing and the last remediated archive was released in July 2011. There are nevertheless still structural errors in the database. Some are easily detectable, for example, erroneous bond lengths and bond angles, steric clashes, or missing atoms. These errors are very frequent (e.g., the number of atomic clashes in the PDB was estimated to be 13 million in 2010), but in principle can be fixed by recomputing coordinates from structure factors or NMR restraints using a proper force field [15]. Other structural errors are not obvious. For example, a wrong protein topology is identified only if new coordinates supersede the obsolete structure or if the structure is retracted [16]. Hopefully, these errors are rare. More common and yet undisclosed structural ambiguities concern the ionization and the tautomerization of biopolymers and ligands (e.g., three different protonation states are...