eBook - ePub

Regular Polytopes

H. S. M. Coxeter

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 368 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Regular Polytopes

H. S. M. Coxeter

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Polytopes are geometrical figures bounded by portions of lines, planes, or hyperplanes. In plane (two dimensional) geometry, they are known as polygons and comprise such figures as triangles, squares, pentagons, etc. In solid (three dimensional) geometry they are known as polyhedra and include such figures as tetrahedra (a type of pyramid), cubes, icosahedra, and many more; the possibilities, in fact, are infinite! H. S. M. Coxeter's book is the foremost book available on regular polyhedra, incorporating not only the ancient Greek work on the subject, but also the vast amount of information that has been accumulated on them since, especially in the last hundred years. The author, professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, has contributed much valuable work himself on polytopes and is a well-known authority on them.

Professor Coxeter begins with the fundamental concepts of plane and solid geometry and then moves on to multi-dimensionality. Among the many subjects covered are Euler's formula, rotation groups, star-polyhedra, truncation, forms, vectors, coordinates, kaleidoscopes, Petrie polygons, sections and projections, and star-polytopes. Each chapter ends with a historical summary showing when and how the information contained therein was discovered. Numerous figures and examples and the author's lucid explanations also help to make the text readily comprehensible.

Professor Coxeter begins with the fundamental concepts of plane and solid geometry and then moves on to multi-dimensionality. Among the many subjects covered are Euler's formula, rotation groups, star-polyhedra, truncation, forms, vectors, coordinates, kaleidoscopes, Petrie polygons, sections and projections, and star-polytopes. Each chapter ends with a historical summary showing when and how the information contained therein was discovered. Numerous figures and examples and the author's lucid explanations also help to make the text readily comprehensible.

Although the study of polytopes does have some practical applications to mineralogy, architecture, linear programming, and other areas, most people enjoy contemplating these figures simply because their symmetrical shapes have an aesthetic appeal. But whatever the reasons, anyone with an elementary knowledge of geometry and trigonometry will find this one of the best source books available on this fascinating study.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Regular Polytopes als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Regular Polytopes von H. S. M. Coxeter im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Matematica & Geometria. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

MatematicaThema

GeometriaCHAPTER I

POLYGONS AND POLYHEDRA

TWO-DIMENSIONAL polytopes are merely polygons ; these are treated in § 1·1. Three-dimensional polytopes are polyhedra ; these are defined in § 1·2 and developed throughout the first six chapters. § 1·3 contains a version of Euclid’s proof that there cannot be more than five regular solids, and a simple construction to show that each of the five actually exists. The rest of Chapter I is mainly topological : a regular polyhedron is regarded as a map, and later as a configuration. In § 1·5 we take an excursion into “ recreational ” mathematics, as a preparation for the notion of a tree of edges in von Staudt’s elegant proof of Euler’s Formula.

1·1. Regular polygons. Everyone is acquainted with some of the regular polygons : the equilateral triangle which Euclid constructs in his first proposition, the square which confronts us all over the civilized world, the pentagon which can be obtained by making a simple knot in a strip of paper and pressing it carefully flat,3 the hexagon of the snowflake, and so on. The pentagon and the enneagon have been used as bases for the plans of two American buildings : the Pentagon Building near Washington, and the Bahá’í Temple near Chicago. Dodecagonal coins have been made in England and Canada.

To be precise, we define a p-gon as a circuit of p line-segments A1 A2, A2 A3, . . . , Ap A1, joining consecutive pairs of p points A1, A2, . . . , Ap. The segments and points are called sides and vertices. Until we come to Chapter VI we shall insist that the sides do not cross one another. If the vertices are all coplanar we speak of a plane polygon, otherwise a skew polygon.

A plane polygon decomposes its plane into two regions, one of which, called the interior, is finite. We shall often find it convenient to regard the p-gon as consisting of its interior as well as its sides and vertices. We can then re-define it as a simply-connected region bounded by p distinct segments. (“ Simply-connected ” means that every simple closed curve drawn in the region can be shrunk to a point without leaving the region, i.e., that there are no holes.)

The most important case is when none of the bounding lines (or “ sides produced ”) penetrate the region. We then have a convex p-gon, which may be described (in terms of Cartesian coordinates) by a system of p linear inequalities

These inequalities must be consistent but not redundant, and must provide the range for a finite integral

(which measures the area).

A polygon is said to be equilateral if its sides are all equal, equiangular if its angles are all equal. If p > 3, a p-gon can be equilateral without being equiangular, or vice versa ; e.g., a rhomb is equilateral, and a rectangle is equiangular. A plane p-gon is said to be regular if it is both equilateral and equiangular. It is then denoted by {p} ; thus {3} is an equilateral triangle, {4} is a square, {5} is a regular pentagon, and so on.

A regular polygon is easily seen to have a centre, from which all the vertices are at the same distance 0R, while all the sides are at the same distance 1R. This means that there are two concentric circles, the circum-circle and in-circle, which pass through the vertices and touch the sides, respectively.

It is sometimes helpful to think of the sides of a p-gon as representing p vectors whose sum is zero. They may then be compared with p segments issuing from one point, the angle between two consecutive segments being equal to an exterior angle of the p-gon. It follows that the sum of the exterior angles of a plane polygon is a complete turn, or 2π. Hence each exterior angle of {p} is 2π/p, and the interior angle is the supplement,

1·11

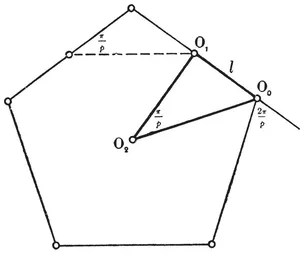

This may alternatively be seen from the right-angled triangle O2 O1 O0 of Fig. 1.1A, where O2 is the centre, O1 is the mid-point of a side, and O0 is one end of that side. The right angle occurs at O1, and the angle at O2 is evidently π/p. If 2l is the length of the side, we have

O0 O1 = l, O0 O2 = 0R, O1 O2 = 1R ;

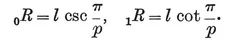

therefore

1·12

The area of {p}, being made up of 2p such triangles, is

1·13

(in terms of the half-side l). The perimeter is, of course,

1·14

FIG. 1.1A

As p increases without limit, the ratios S/0R and S/1R both tend to 2π, as we would expect. (This is how Archimedes estimated π, taking p=96.)

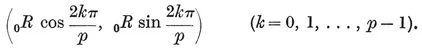

We may take the Cartesian coordinates of the vertices to be

Then, in the Argand diagram, the vertices of a {p} of circum-radius 0R=1 represent the complex numbers e2kπi/p, which are the roots of the cyclotomic equation

1·15

It is sometimes desirable to extend our ...