eBook - ePub

Feedback Control Theory

John C. Doyle, Bruce A. Francis, Allen R. Tannenbaum

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 224 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Feedback Control Theory

John C. Doyle, Bruce A. Francis, Allen R. Tannenbaum

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

An excellent introduction to feedback control system design, this book offers a theoretical approach that captures the essential issues and can be applied to a wide range of practical problems. Its explorations of recent developments in the field emphasize the relationship of new procedures to classical control theory, with a focus on single input and output systems that keeps concepts accessible to students with limited backgrounds. The text is geared toward a single-semester senior course or a graduate-level class for students of electrical engineering.

The opening chapters constitute a basic treatment of feedback design. Topics include a detailed formulation of the control design program, the fundamental issue of performance/stability robustness tradeoff, and the graphical design technique of loopshaping. Subsequent chapters extend the discussion of the loopshaping technique and connect it with notions of optimality. Concluding chapters examine controller design via optimization, offering a mathematical approach that is useful for multivariable systems.

The opening chapters constitute a basic treatment of feedback design. Topics include a detailed formulation of the control design program, the fundamental issue of performance/stability robustness tradeoff, and the graphical design technique of loopshaping. Subsequent chapters extend the discussion of the loopshaping technique and connect it with notions of optimality. Concluding chapters examine controller design via optimization, offering a mathematical approach that is useful for multivariable systems.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Feedback Control Theory als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Feedback Control Theory von John C. Doyle, Bruce A. Francis, Allen R. Tannenbaum im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Technologie et ingénierie & Ingénierie de l'électricité et des télécommunications. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Without control systems there could be no manufacturing, no vehicles, no computers, no regulated environment—in short, no technology. Control systems are what make machines, in the broadest sense of the term, function as intended. Control systems are most often based on the principle of feedback, whereby the signal to be controlled is compared to a desired reference signal and the discrepancy used to compute corrective control action. The goal of this book is to present a theory of feedback control system design that captures the essential issues, can be applied to a wide range of practical problems, and is as simple as possible.

1.1 Issues in Control System Design

The process of designing a control system generally involves many steps. A typical scenario is as follows:

1.Study the system to be controlled and decide what types of sensors and actuators will be used and where they will be placed.

2.Model the resulting system to be controlled.

3.Simplify the model if necessary so that it is tractable.

4.Analyze the resulting model; determine its properties.

5.Decide on performance specifications.

6.Decide on the type of controller to be used.

7.Design a controller to meet the specs, if possible; if not, modify the specs or generalize the type of controller sought.

8.Simulate the resulting controlled system, either on a computer or in a pilot plant.

9.Repeat from step 1 if necessary.

10.Choose hardware and software and implement the controller.

11.Tune the controller on-line if necessary.

It must be kept in mind that a control engineer's role is not merely one of designing control systems for fixed plants, of simply “wrapping a little feedback” around an already fixed physical system. It also involves assisting in the choice and configuration of hardware by taking a systemwide view of performance. For this reason it is important that a theory of feedback not only lead to good designs when these are possible, but also indicate directly and unambiguously when the performance objectives cannot be met.

It is also important to realize at the outset that practical problems have uncertain, non- minimum-phase plants (non-minimum-phase means the existence of right half-plane zeros, so the inverse is unstable); that there are inevitably unmodeled dynamics that produce substantial uncertainty, usually at high frequency; and that sensor noise and input signal level constraints limit the achievable benefits of feedback. A theory that excludes some of these practical issues can still be useful in limited application domains. For example, many process control problems are so dominated by plant uncertainty and right half-plane zeros that sensor noise and input signal level constraints can be neglected. Some spacecraft problems, on the other hand, are so dominated by tradeoffs between sensor noise, disturbance rejection, and input signal level (e.g., fuel consumption) that plant uncertainty and non-minimum-phase effects are negligible. Nevertheless, any general theory should be able to treat all these issues explicitly and give quantitative and qualitative results about their impact on system performance.

In the present section we look at two issues involved in the design process: deciding on performance specifications and modeling. We begin with an example to illustrate these two issues.

Example A very interesting engineering system is the Keck astronomical telescope, currently under construction on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. When completed it will be the world’s largest. The basic objective of the telescope is to collect and focus starlight using a large concave mirror. The shape of the mirror determines the quality of the observed image. The larger the mirror, the more light that can be collected, and hence the dimmer the star that can be observed. The diameter of the mirror on the Keck telescope will be 10 m. To make such a large, high-precision mirror out of a single piece of glass would be very difficult and costly. Instead, the mirror on the Keck telescope will be a mosaic of 36 hexagonal small mirrors. These 36 segments must then be aligned so that the composite mirror has the desired shape.

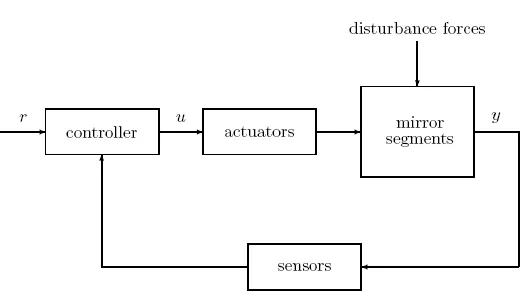

The control system to do this is illustrated in Figure 1.1. As shown, the mirror segments are subject to two types of forces: disturbance forces (described below) and forces from actuators. Behind each segment are three piston-type actuators, applying forces at three points on the segment to effect its orientation. In controlling the mirror’s shape, it suffices to control the misalignment between adjacent mirror segments. In the gap between every two adjacent segments are (capacitor-type) sensors measuring local displacements between the two segments. These local displacements are stacked into the vector labeled y; this is what is to be controlled. For the mirror to have the ideal shape, these displacements should have certain ideal values that can be pre-computed; these are the components of the vector r. The controller must be designed so that in the closed-loop system y is held close to r despite the disturbance forces. Notice that the signals are vector valued. Such a system is multivariable.

Our uncertainty about the plant arises from disturbance sources:

•As the telescope turns to track a star, the direction of the force of gravity on the mirror changes.

•During the night, when astronomical observations are made, the ambient temperature changes.

Figure 1.1: Block diagram of Keck telescope control system.

•The telescope is susceptible to wind gusts.

and from uncertain plant dynamics:

•The dynamic behavior of the components—mirror segments, actuators, sensors—cannot be modeled with infinite precision.

Now we continue with a discussion of the issues in general.

Control Objectives

Generally speaking, the objective in a control system is to make some output, say y, behave in a desired way by manipulating some input, say u. The simplest objective might be to keep y small (or close to some equilibrium point)—a regulator problem—or to keep y − r small for r, a reference or command signal, in some set—a servomechanism or servo problem. Examples:

•On a commercial airplane the vertical acceleration should be less than a certain value for passenger comfort.

•In an audio amplifier the power of noise signals at the output must be sufficiently small for high fidelity.

•In papermaking the moisture content must be kept between prescribed values.

There might be the side constraint of keeping u itself small as well, because it might be con...