![]()

1

An introduction to the historical context

The pages that follow focus on the visual expression of rulership in Armenia during the years 884/85–1045 CE, a time commonly, if inaccurately, referred to as the Bagratuni period. It was during this time that the palace church of the Holy Cross at Aght‘amar and the city of Ani were built, to list only the most famous of the surviving monuments. While there is a sizeable literature on the royal art and architecture of this period, the paucity of surviving comparanda has too frequently resulted in the monuments being presented in sterile isolation, explained only internally through an analysis of their own components. There has been little attempt to interpret the message of these works through the study of their original contexts. There has also been no attempt to integrate them within the chronological scope of the period, or across the socio-political divisions that existed during those years.

What I propose is a reconstruction of the visual expression of rulership of this period through the analysis of objects and texts associated with the two most prominent Armenian families, focusing on art, ceremonial and royal deeds. There is a wealth of contemporary texts that have been edited and (mostly) translated into languages accessible to western readers. These texts have much to offer: they provide descriptions of cities, buildings and works of art that have long since disappeared. They are also rich with descriptions of ceremonial, a prominent and visual component of medieval Armenian rulership, and provide invaluable details about the diplomatic missions and gift-giving that provided some stability in a turbulent time. Through these new details, these texts grant us a new perspective on the society and the people who created the art and architecture examined in the following pages. The writings of the contemporary Armenian historians thus allow us to set those objects that remain more clearly in their original context, and to see their messages from perspectives that are closer to those who created and viewed them.

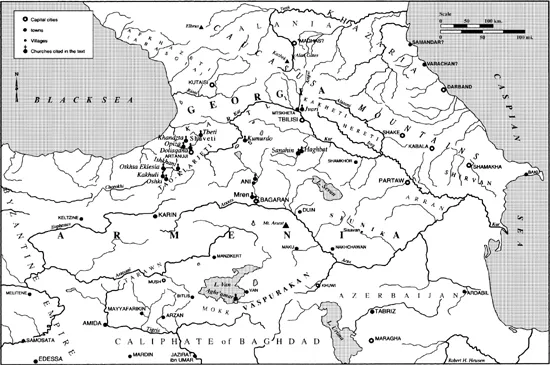

Medieval Armenia was made up of a collection of principalities ruled by nakharars, members of the hereditary Armenian nobility.1 The most important families were the Bagratuni, with lands in the north, and the Artsrunik‘ in the south (Figure 1.1).2 Regional loyalties dominated, and ideas of Armenian unity were largely conceptual – reflecting adherence to a common language or to a common Christian confession rather than to the pre-eminence of any single political entity. From the end of Arsacid rule in 428 until 884/85 there was no king of Armenia; instead it was the prince (ishkhan) and, in the ninth century, the presiding prince (ishkhan ishkhanats‘), who was recognized as the authority over all other Armenian princes.3 Armenia was not autonomous; during the period covered in these pages it was a vassal state of the Abbasid caliphate – the Arminya of Arabic records. The country was administered by a resident governor, or ostikan, appointed by the caliphate, whose principal residence was in Partaw, in modern-day Azerbaijan.4 The prince of Armenia was entrusted with the collection and forwarding of taxes to the ostikan, was prevented from minting his own coins, and was required to provide military service when necessary. Byzantium had no similar in situ political representative in Armenia, but nevertheless considered Armenia to be its vassal state. Accordingly, it responded in kind to each Islamic recognition of Armenian princes and nobility.

Even the term ‘Armenia’ is problematic; the country was only briefly unified under the rule of a single king who was acknowledged by all the nakharars. In 884/85 Prince Ashot Bagratuni was invested by the ostikan, and as Ashot I, became Armenia’s first medieval king. Ashot’s successors faced formidable challenges, including the increasing strength of the ostikan’s control of the country and the eastward expansion of the Byzantine empire into Armenian territory.5 Bagratuni rule was further undermined by civil wars that raged constantly amongst the Armenian noble houses and by nakharars intent on usurping Bagratuni power or on freeing themselves from Bagratuni suzerainty. In 908 Gagik Artsruni, grandson of Ashot I, established the independent southern Armenian kingdom of Vaspurakan. By the second half of the tenth century rivalries within the Bagratuni family further partitioned what is generally (if confusingly) referred to as the kingdom of Armenia. While the main branch of the Bagratuni family continued to rule this northern kingdom, members of the minor branches of the family were granted possession of lands that traditionally fell under the king of Armenia’s suzerainty, resulting in the establishment of several petty kingdoms, including Tarōn, Siunik‘, Kars and Tashir-Dzoraget.6

We know little of the history of the southern Armenian kingdom of Vaspurakan beyond the life of the founder of the Arstruni dynasty, Gagik Artsruni. From 919 until the death of Gagik Artsruni some time after 943, Vaspurakan was the most powerful kingdom in Armenia. Gagik was the target of continuous attack by the ostikan(s), and his military prowess seems only to have increased with age. In the late 930s he joined forces with the Bagratuni king Abas, rescuing Abas from certain death with his timely arrival, and subsequently defeating the Arab armies.7 In 940 we find Gagik summoned to the Arab-controlled town of Khlat (modern Khilat) on the northwest shore of Lake Van, where he swore an oath of vassalage to the Hamdanid emir Sayf al-Dawla, who presented Gagik with ‘great honours’.8 In the Arabic account of this meeting, Gagik is titled ‘king of Armenia and Iberia’. He is given the same title in an account of a second summons which occurred the same year, where his name is given pride of place over the other attendant Armenian nakharars and the Bagratuni king.9

Gagik’s authority was also recognized in Byzantium. The emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905–59), listing the forms of address given to the Armenian kings gives the title archōn tōn archontōn to both Abas Bagratuni and Gagik Artsruni, while addressing all other nakharars as archōn.10 The final historical reference to Gagik dates to the year 943, when a deposed ostikan sought refuge with Gagik on the island of Aght‘amar.11 It is not known when or how Gagik met his death. His son Derenik is only briefly mentioned by historians, and Vaspurakan fades from recorded history until its last king, Senek‘erim, cedes the kingdom to the emperor Basil II in 1021–22 in exchange for the city of Sebastia in Cappadocia.12

The Bagratuni kingdom of Armenia came into ascendancy after the reign of Gagik Artsruni, but was politically weakened by division. While the fragmentation of Armenia began in 908 with the ostikan’s recognition of a king of Vaspurakan, the greatest blow to unified Bagratuni rule was inflicted by Ashot III (r. 952/53–977), who began the practice of awarding royal titles to members of his extended family. While these petty kings proliferated, Armenia was also being inexorably absorbed by Byzantium. By the first quarter of the eleventh century, the rulers of Tarōn, Vaspurakan and most of Siunik‘ had ceded control to the Byzantine emperor, and the dispossessed rulers emigrated to Byzantine Cappadocia.13

In 1045 the Bagratuni king of Ani, Gagik II, was also forced by the Byzantine emperor to abdicate and move to lands in Cappadocia.14 Gagik of Kars, another member of the Bagratuni family, relinquished his northern Armenian kingdom to the emperor and moved to Tzamandos in Cappadocia in 1063.15 By 1064 the Seljuks had captured most of the Armenian territories from Byzantium, including Ani and Vaspurakan.16 The defeat of the emperor at Manzikert in 1071 effectively ended Byzantine rule in Armenia, and at the same time ended any remaining vestige of independence in the historic lands of Armenia. The new Armenian kingdom of Cilicia, officially established in 1198 but in existence since the late tenth century, carried on the tradition of Armenian independence, to be followed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries by the revival of Greater Armenia.17

Two contemporary historians offer much information on the early years of this period. John (Yovhannēs) Draskhanakerttsi‘ was the catholicos of the Armenian Church from 897/98 to 924/25. Known as John Catholicos, he wrote The History of Armenia to illustrate the fatal consequences of civil war to the feuding nakharars. He came to know his subject well. He began writing his book under the patronage of the Bagratuni kings, but was forced by civil war and the ostikan’s persecution to flee south. He finished his work on the island of Aght‘amar, under the protection of Gagik Artsruni.18 A second important text for this period is The History of the House of the Artsrunik‘, written by Thomas [T‘ovma] Artsruni, a kinsman of Gagik Artsruni and a contemporary of John Catholicos. The work was commissioned by Gagik to glorify the ancestry and accomplishments of his family. Thomas records events through 904, when the narrative is taken up by an anonymous continuator who ...