![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The province of Champagne

There is no denying that Champagne is one of the more prosaic parts of France. It lacks the natural beauty and wildness of the Alps or Auvergne, the cultural and ethnic distinctiveness of Brittany, the allure of Provence and the Côte d’Azur, or the brilliance and importance of Paris. Visitors are unlikely to spend much time in the region, unless it is to sample the wares of the great Champagne houses in Reims or Epernay, or to wander the narrow cobbled streets of the old town of Troyes, known as ‘le Bouchon de Champagne’ for its distinctive shape rather than any association with the sparkling wine.

Historically, as well, there seems little special about the province, at least since the decline of the great commercial fairs of the Middle Ages and the absorption of the territory of the Counts of Champagne into the royal domain in the thirteenth century. (The possessions of the counts never took in all of what would become province – the archbishop of Reims, the bishop of Châlons, and the bishop of Langres remained territorial rulers outside of the counts’ jurisdiction.) Lacking its own provincial assembly or états, or a provincial parlement, the region never had a distinctive voice or identity as did Burgundy, Normandy or Languedoc, to name but a few. As A.N. Galpern wrote in his study of the region’s religious culture in the sixteenth century, ‘Champagne was at once too far from Paris and not far enough – too far to be galvanized by the capital and share in its animation, too close to enjoy life on its own.’1 As a result, despite its historical importance and proximity to Paris, it is one of the least studied areas of France.2

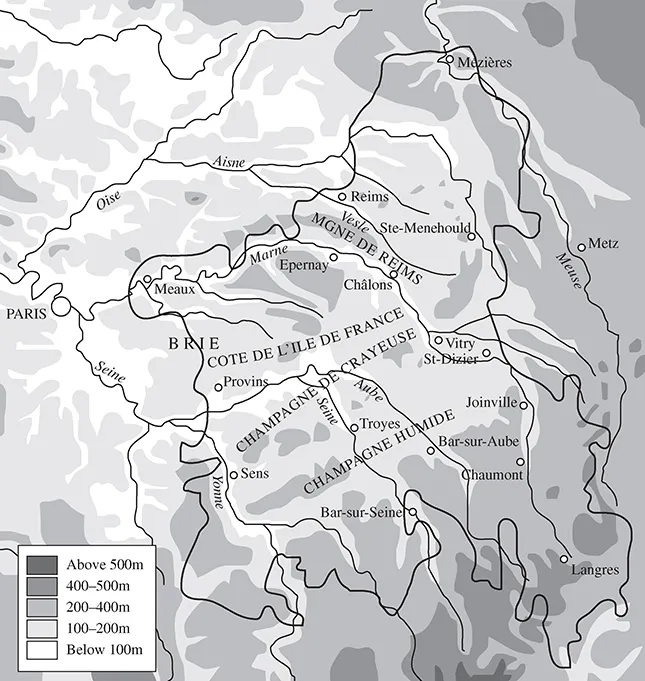

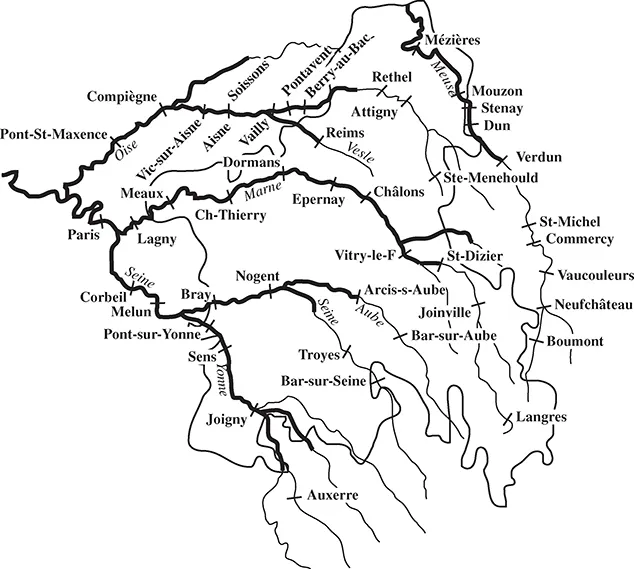

Yet Champagne’s apparent ordinariness should not mislead us. If there is little to draw a visitor to the region, Champagne is situated at an important crossroads. Bounded to the northeast by the Ardennes and the heavily forested upland of the Argonne, to the east by the Côte de Meuse, to the southwest by the Morvan and to the south by the hills of Burgundy, anyone travelling from the east or south to Paris or elsewhere in France is almost bound to travel through Champagne. Indeed, as Galpern notes, ‘Champagne’s vocation, ever since men have settled the area, has been to link more important places to one another.’3 As Map 1.4 shows, the major routes from western Germany, Lorraine, Burgundy and Switzerland to Paris and the French heartland all led through the province. In Roman times, the major route from Italy to the Channel led through Champagne. Reims was a bustling Gallo-Roman centre while Paris was a struggling collection of huts on an island in the Seine. During the Middle Ages, it was this position which allowed the Counts of Champagne to establish the famous fairs which were the commercial and financial clearinghouses for merchants from Italy and the Low Countries. By the sixteenth century, the fairs of Champagne had been eclipsed by Paris and Lyon, but Champagne’s essential nature as a crossroads endured. Geographically, Champagne forms part of the eastern section of the Parisian Basin, the region lying between the Ardennes, Vosges, Massif Central and the Massif Armoricain of Britanny. Topographically, Champagne consists of three concentric arcs, with their open sides facing west, towards Paris, and each sloping gently from east to west. The middle of these three arcs contains Champagne’s most obvious geographic feature: the open plains (champs) which give the province its name. This is Champagne crayeuse, or ‘chalky Champagne’, where the chalky soils can be blinding on a sunny day. Rainfall is quickly absorbed by this light and porous soil where it finds its way into the rivers and streams which flow through the area; as a result the settlement pattern here is one of agricultural villages clustered along the banks of the region’s rivers and streams. This region is also known as Champagne pouilleuse or ‘barren Champagne’, because of its reputed monotony and poverty. This reputation, however, seems to date from the seventeenth century, when the district suffered from the demographic crises of that era, and before the advent of the sparkling wine revivified it. Thus Michelet described it as ‘a sad sea of stubble amid an immense sea of plaster’.4 There has been little ‘pouilleuse’ about the region before or since. The light, well-drained soils were easy to work, and Champagne crayeuse was as important a granary as better known regions such as the Beauce and Valois.5 The land was also ideal for sheep-grazing, giving rise to important textile industries in Troyes, Châlons and Reims. Nowadays, the district is dominated by large agribusinesses growing grain and sugarbeets.

To the west lies the plateau of Brie, separated from Champagne crayeuse by the escarpment of the Côte de l’Ile de France. Here the chalk soils lie beneath the surface of clay, and the region is characterized by forests and swamps, and used primarily for grazing. By the accidents of feudal succession, the eastern part of Brie (or Brie champenoise) came under the dominion of the Counts of Champagne, and thus was later part of the province of Champagne, while the more fertile western part was part of the Ile de France. Nevertheless, economic, political and historic ties linked Brie champenoise with the rest of Champagne to the east.6

To the east of Champagne crayeuse, beyond the low and intermittent Côte de Champagne, lies the narrow arc of Champagne humide (20 to 25 km in width), so called not because it receives more rainfall, but because, like Brie, its clayey soils repel moisture as much as the chalk of Champagne crayeuse absorbs it, resulting in a landscape of marshes, lakes and forests. To the east, beyond the Argonne in the north and the Côte de Meuse further south, lie the Barrois and Lorraine.

Besides its transportation corridors on land, Champagne is traversed by a number of navigable rivers: the Aisne, the Marne, the Aube, the Seine and the Yonne. The major river crossings and navigable sections of the rivers are shown in Map 1.2. The Meuse, further to the east, flows into the North Sea; hence while it was an important river in its own right, for east-west transit it was an obstacle rather than a corridor. The Meuse was navigable downstream from Verdun, although its importance for Champagne, in this period at least, was minor. It would prove to be more important during the wars of the seventeenth century and later, when it was crucial to the supply of French armies in the Netherlands and Germany.7 The Aisne, with its source in the Argonne flows northwest past Ste-Menehould before curving to the west past Rethel and Soissons. Just past Compiègne, and beyond the frontier of Champagne, it flows into the Oise, which in turn joins the Seine just below Paris. It was capable of carrying boats beginning at Château-Porcien, just downstream of Rethel.8 The Vesle, a tributary of the Aisne, flows past Reims, and then around the northern side of the Montagne de Reims before joining the Aisne just east of Soissons. Charles, cardinal de Lorraine (d. 1574) had begun a project to make the river navigable below Reims.9

The Marne, with its source near Langres, winds its way in a northwesterly direction until Châlons when it turns west, flowing past Epernay (where it pierces the bluffs of the Côte de l’Ile de France), Château-Thierry and Meaux, before joining the Seine at Charenton, just above Paris. Navigable beginning at Saint-Dizier, the Marne was one of Paris’s major supply arteries, bringing downstream to the capital ‘wood for burning and for construction, charcoal, iron, plaster, millstones, wheat, flour, barley, oats, hay, wine, etc.’.10 Among the tributaries of the Marne, the Grand Morin and Ourcq were navigable; the former from Tigeaux to Condé where it flows into the Marne, just below Meaux, and the latter from La Ferté-Milon to Mary.11 The Saulx served as transit corridor between Lorraine and Champagne, flowing past Vitry-en-Perthois, and joining the Marne near the site of the new town of Vitry-le-François.12 The Aube is born on the plateau of Langres and flows in a northwesterly direction across Champagne crayeuse, joining the Seine below Troyes. Though it was capable of floating logs almost from its source, navigation did not begin until Arcis-sur-Aube, north of Troyes.13

The Seine has been a crucial artery of navigation since at least Gallo-Roman times, linking up through overland passages the basins of the Rhône and Loire (and hence the Mediterranean and Atlantic) with the Channel and the North Sea. This in large part explains the medieval dominance of the Champagne fairs, all within easy reach of the Seine and its tributaries.14 From its source in Burgundy, northwest of Dijon, it flows, like all rivers in Champagne, in a northwesterly direction past Châtillon-sur-Seine, Bar-sur-Seine and Troyes. Just past Troyes, near Romilly, it is turned to the southwest by the plateau of Brie where it is joined by the Aube. At Montereau, it is joined by the Yonne and turns to the north, flowing through ...