![]()

Part I

Future at the heart of the ageing region

![]()

1 Demographic change as dystopia

Contemporary German discourses on ageing, between science and politics

Reinhard Messerschmidt

Embedded in a long tradition of demographic dystopias, which Spanish demographer Andreu Domingo (2008) examined in the popular literature of the last two centuries, contemporary discourses of demographic change raise a variety of questions. Over 20 years ago, gerontologist Stephen Katz stated that ‘popular and professional discourses which currently accentuate the demographic features of aging populations are characterized by their alarmism’ and named this phenomenon ‘alarmist demography’ (1992, p. 204). He situated such alarmism in governmental narratives on the aged sub-population and its collective dependency, where popular media and think tanks ‘depict the elderly emptying the coffers of the welfare state and creating a tax burden beyond the means of the labour force to support’, giving the appearance that ‘the growing aging population is threatening to create an economic crisis with profound consequences for healthcare systems, social security programmes, industrial and intergenerational relations’ (ibid., pp. 203–204). This chapter will resituate in the present what he could see so clearly in the past.1 Demographic change, typically understood as the ageing of the population (Schimany, 2003) with respect to its subsequent shrinkage (Kaufmann, 2005), has become commonplace in German social-science and mass-media discourse since the turn of the millennium. Although the ‘fear of population decline’ ebbed and flowed over the past century, according to Teitelbaum and Winter (1985, p. 1), ‘depending both upon demographic realities and perceptions of the links between population change and economic, social, and political power’, the ‘flow’ of contemporary discourses should be understood in the context of strategies of governmentality addressing individual and population ageing. In fact, the current flow can be interpreted as resulting from the prevailing economization of the social (Bröckling, 2007) and embedded in specific programmes of governmentality, such as the growing entrepreneurship of the self(s), which can no longer expect social care from the state. Declarations that social security systems are endangered and consequently need to be increasingly privatized are legitimized by demographic claims to knowledge of the future, which we will refer to as ‘future knowledge’ (Hartmann & Vogel, 2010). This can be interpreted as being part of contemporary ‘neosocial governmentality’ (Lessenich, 2008) or the ‘neosocial market economy’ (Vogelmann, 2012). As this chapter will show, privatization of benefits (for insurance companies, the financial market, and the ‘silver economy’ driven by the rising consumption by older people and for age-specific needs) contrasts with the socialization of costs (e.g. prolonged working life/later retirement, ‘active’ and productive ageing, direct or indirect cuts in social insurance). Nevertheless, governmental programmes and associated governments of the self are not necessarily successful (Bröckling et al., 2010), because individuals can always partially or entirely reject the related discourses.2

This chapter’s main objective is to reveal the order of demographic future knowledge and its discursive depth structures (Diaz-Bone, 2013), in the sense of underlying orders of thought and communicational power (Reichertz, 2015). Foucault’s manifold legacy (Messerschmidt, 2016) allows examination of its conditions of possibility. The chapter thus analyses both of the discursive fields that provide the fundamentals of a specific contemporary governmentality of demographic change. The first section, concerning the fabrication of demographic future knowledge, focuses on the underlying ‘rationality’ consisting of key categories, measures (e.g. fertility rates or dependency ratios), and population projections in the scientific field, and the following section empirically situates ‘garbled demography’ (Teitelbaum, 2004) in the present by describing discursive regularities in 3810 German media texts dating from 2000 to 2013. The final section will connect these discursive fields to ‘demographization’ (Barlösius, 2007, 2010) and outline a specific governmentality of demographic change.

The order of demographic future knowledge

Foucauldian analysis of the discourse of demographic change starts with its underlying epistemological orders, in sense of rules or, as he called it, the ‘system of formation’ (1972, p. 43), a thought system containing categories, measures and concepts that serve as conditions for the related statements’ existence. Before any assumptions can be asserted about the demographic future, it is necessary to know the present. Already at this stage, scientific discourse contains a variety of observable problems that will be summarized in what follows. Despite all possible ruptures, demographic thought has a central regularity: a territorially defined population and its dynamics. Defining a population involves both the inclusion and exclusion of people. The latter is closely tied to the concept of nation-state and reflected in the genealogically problematic concept of ‘Volk’ as ‘community of descent’ in Germany (Brubaker, 1990, p. 396, Overath & Schmidt, 2003; see also Nilssen’s chapter in this volume for a Swedish perspective), in its implicit or even explicit form (Etzemüller, 2007, p. 145). Meanwhile, a minority of German demographers have demonstrated the constructivist character of the concept of ‘population’ (Mackensen et al., 2009). A population is constructed insofar as it depends on borders drawn in relation to the historical development of the nation-state and political decisions (Etzemüller, 2008, p. 203). At first glance, the resulting distinction between national citizens and ‘others’ resulting from such boundaries appears obvious, but the issue becomes problematic with further reflection. The approximate estimates of ‘illegal’ migration (for lack of data) are but one of the problems. This distinction is still visible (and quite questionable) when demographic models exclude the German-citizen children of immigrants and continue to assume that there are two separate sub-populations (Bohk, 2012), one allegedly ‘autochthonous’ and another that will never lose the ‘migrant-background’ label. The key demographic concept of population is neither neutral nor natural. There are currently only two published monographs dealing with German ‘population discourse’ (Hummel, 2000; Etzemüller, 2007), both of which conceptualizing it as a substantially monolithic discourse that can be traced back to the emergence of demography in the late eighteenth century. These publications unquestionably contribute to a better understanding of the history of contemporary demographic discourse, whereas this chapter devotes more attention to discourses of demographic change in the present. The sociologist Diana Hummel (2000, p. 15) identified demography as a genuine ‘political science’ and pointed out that ‘population’ was clearly already a political concept starting with the emergence of the study of demography as the explanation and prognostication of population dynamics for political regulation purposes. Her detailed and demographically informed analysis has great historical depth, starting with the emergence of demography in the late eighteenth century, but ends exactly at the moment when discourses of demographic change become widespread in the German public via the mass media. For this reason, the analysis presented in this chapter covers the years 2000 to 2013. Furthermore, Michel Foucault’s later works (2007, 2008, 2010, 2011) were not yet available when Hummel wrote her monograph.

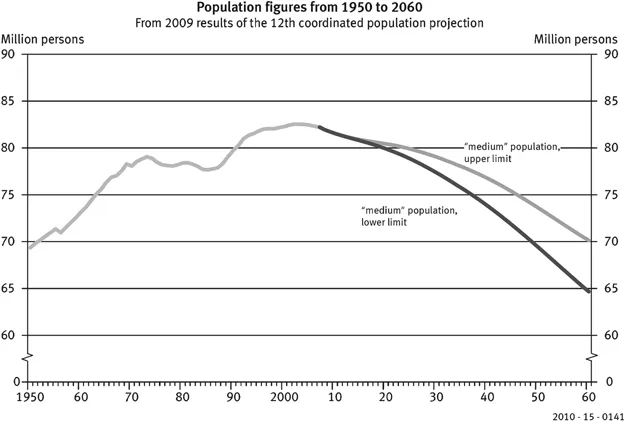

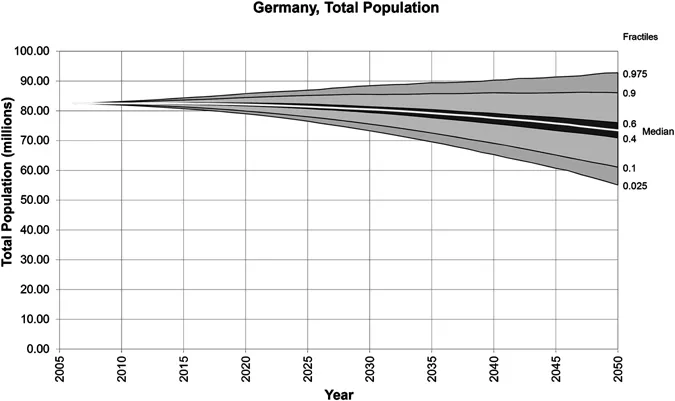

Demographic processes are primarily visible through numbers, which demographers produce, calculate and interpret. Etzemüller’s position (2008, p. 210), that ‘the discourse works only through its visualization, because demographic processes as such are invisible’ lacks additional focus on the underlying epistemic regularities concerning the measurement of these processes. Nevertheless, visualization plays a crucial role in framing media reception: although demographic discourses cannot be entirely reduced to visualization, graphs do in some ways produce stronger statements compared to tables or sentence form. This is caused by a ‘symbolic surplus’, as Eva Barlösius termed it in her critique of the ‘demographization of the social’ (2007, p. 17), characterized by graphs that evoke one specific interpretation of the consequences (2010, p. 232). Population pyramids, popularized by Friedrich Burgdörfer in 1932 (Etzemüller, 2007, p. 85) and still used for describing a population’s changing age structure, already present a strongly normative framework for interpretation. The visual scheme – from the age-structure ‘pyramid’ of circa 1900 to the ‘urn’ of 2050 – is indeed a classic feature of ‘apocalyptic’ population discourses. Technically, this scheme is rooted in an ‘ideal’ total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.1 children per woman, the so-called replacement fertility rate for a stationary population. Implicitly embedded interpretation is rarely as obvious as in this case, however. Looking at a recent press release from the German Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) presenting the future of the German population over the next 50 years reveals many interesting details. In the German versions3 (e.g. Destatis, 2015a), the subtitle reads ‘coordinated pre-calculation of the population’ instead of speaking of coordinated population projection. This slight difference reflects the notable tension with Destatis’ deterministic population projections (see Figure 1.1). Comparison to a probabilistic projection by the Vienna Institute of Demography (VID, see Figure 1.2), which is also scenario-based but includes uncertainty in the visualization, makes the main difference in the power of each statement visible.

The Destatis graph only shows the outcome of two ‘moderate’ scenarios that clearly indicate a decline, whereas the VID projection shows a possible range of outcomes under the given premises with different probabilities. In absolute numbers,4 there is no significant difference between the results of Destatis’ upper limit scenario and the median of the VID projection. However, the graph from Destatis lacks information that is provided in the VID graph, and the scales of the axes are strikingly different. While the x-axis shows a lengthy historical time horizon before the projection period starts, the y-axis has an unusual gap between 0 and 60. The consequence of both modifications is a more dramatic (visual) decline, resulting in the first graph containing a more ‘newsworthy’ statement. If we treat each population projection graph as a discourse, namely a ‘group of statements that belong to a single system of formation’ (Foucault 1972, p. 107), the task is to analyse the system of formation of each one. Although the premises of both graphs are comparable, the conclusions to which they allude are fundamentally different. Both projections refer to the same measures and produce a very similar range of results (at least as numerically5 represented in tables), but they differ strongly in visualization, especially where considerations of uncertainty are concerned. Population projections can only be as good as the underlying assumptions about the future development of fertility, mortality and migration. Destatis uses twelve scenarios combined with three additional ‘model-calculations’, but most of these scenarios are excluded in Figure 1.1. Their underlying assumptions are described in tables in the appendix, without results or visualization (2009, pp. 36–41); the results of these scenarios can only be downloaded separately as an Excel spreadsheet. If we compare these assumptions with indicators’ past trajectories, all scenarios have an artificially static character in common, so the difference between a scenario and ‘model-calculation’ seems to vanish.

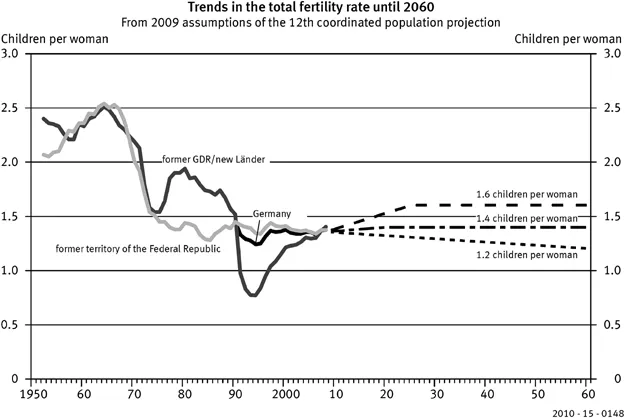

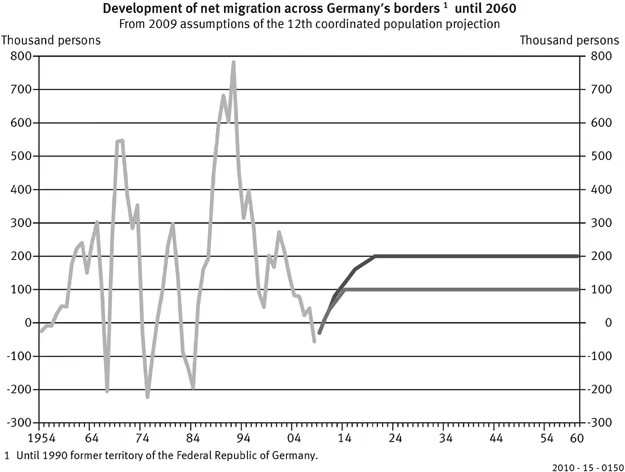

The TFR (see Figure 1.3) has obviously declined since the 1960s, in both parts of Germany. Although the declining trend is well documented for the past, experts designing scenarios are confronted with Hume’s problem of induction (a.k.a. ‘Russell’s inductivist turkey’6): why should the trend continue? Even assuming that it does, the three stable scenarios offered by Destatis’ experts are still epistemologically questionable, especially regarding limitations of the TFR metric described later in this chapter. The premises become even more problematic if we look at net migration (see Figure 1.4). The only two options included in Destatis’ projections are either 100,000 or 200,000 persons per year. But these numbers had already been noticeably surpassed by 2011 (Destatis, 2012), and in 2012 net migration was nearly twice as high as the higher scenario, with 394,900 people (Destatis, 2013). This is not a case of an unexpected ‘black swan’,7 however, since migration is well known as an unpredictable factor that is highly dependent on political decisions.