![]() Section 1

Section 1

Introduction to Design for Services![]()

1.1

A New Discipline

Service design, as a new discipline, emerged as a contribution to a changing context and to what a certain group of design thinkers (notably Morello 1991,1 Hollins and Hollins 1991, Manzini 1993, Erlhoff et al. 1997, Pacenti 1998) started to perceive and describe as a new design agenda. In the 1990s the growing economic role of the service sector in most of the developed economies was in clear contrast to the then dominant practices and cultures of design, which still focused on the physical and tangible output of the traditional industrial sectors.

As Richard Buchanan has asserted ‘design problems are “indeterminate” and “wicked” because design has no special subject matter of its own apart from what a designer conceives it to be’ (Buchanan 1992: 16). This means that the objects and practices of design depend more on what designers perceive design to be and not so much on an agreed on or stable definition elaborated by a scientific community.

The subject matter of design is potentially universal in scope, because design thinking may be applied to any area of human experience (Buchanan 1992: 16).

The growing relevance of the service sector has affected not only design but several disciplines, starting from marketing and management moving to engineering, computing, behavioural science, etc.; recently a call for a convergence of all these disciplines has claimed the need for a new science, a ‘Service Science’ (Spohrer et al. 2007, 2008, Pinhanez and Kontogiorgis 2008, Lush et al. 2008), defined as ‘the study of service systems, aiming to create a basis for systematic service innovation’ (Maglio and Spohrer 2008: 18).

This book explores what design brings to this table and reflects on the reasons why the ideas and practices of service design are resonating with today’s design community. It offers a broad range of concrete examples in an effort to clarify the issues, practices, knowledge and theories that are beginning to define this emerging field. It then proposes a conceptual framework (in the form of a map) that provides an interpretation of the contemporary service design practices, while deliberately breaking up some of the disciplinary boundaries framing designing for services today.

Given the richness of this field, we followed some key principles to build and shape the contents of this publication:

1. We decided to select service projects that have a direct and clear relationship with consolidated design specialisations (such as interaction design, experience design, system design, participatory design or strategic design) or manifesting a designerly way of thinking and doing (Cross 2006), despite the diverse disciplinary backgrounds;

2. We aimed at organising the different contributions into a systemic framework delineating a field of practice characterised by some clear core competences, but having blurred and open boundaries. This framework in particular illustrates the multidimensional nature of contemporary design practice and knowledge, apparently fragmented in its description, but actually able to identify, apply and assimilate multiple relevant contributions coming from other disciplines;

3. We recognised how services, like most contemporary artefacts (Morin 1993), are impossible to control in all their aspects, because of their heterogeneity and high degree of human intensity. In this book we therefore applied the principles of ‘weak thinking’ (Vattimo and Rovatti 1998), meaning accepting the fundamental inability of design to completely plan and regulate services, while instead considering its capacity to potentially create the right conditions for certain forms of interactions and relationships to happen.

For these reasons the title of this publication is Design for Services instead of Service Design (or Design of Services). While acknowledging service design as the disciplinary term, we will focus more on articulating what design is doing and can do for services and how this connects to existing fields of knowledge and practice.

This reflection is timely and extremely relevant as more and more universities, design consultancies and research centres are willing to enter the field of design for services; we hope that by proposing an orienting framework and a sort of service designers’ ‘identikit’, we will provide a foundation for these growing initiatives while stimulating further conversations and research.

The book introduces a map (described in Chapter 2.5) that illustrates how designers and design research are currently contributing to the design for services. We generated this map by collecting and reflecting on 17 case studies of design and research projects that have been reported and described in Section 2 of this publication.

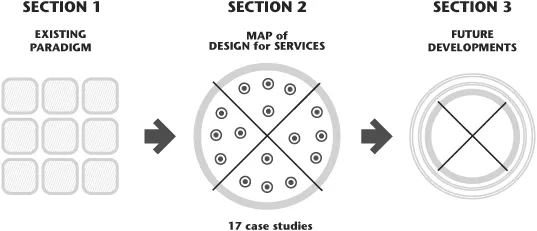

Figure 1.1 The structure of this book

As a support and complementation to the case studies, Section 1 links design for services to existing models and studies on service innovation and service characteristics; while Section 3 projects design for services into the emerging paradigms of a new economy to help us reflecting on its possible future development.

As Kimbell pointed out (Kimbell and Seidel 2008, Kimbell 2009) design for services is still an emerging discipline based on mainly informal and tacit knowledge, but it may develop into a more structured discipline if it develops a closer dialogue with existing disciplines such as service management, service marketing, or service operations. We have opened up and engaged in this closer dialogue throughout this book, in particular considering ‘service marketing’ as historically encompassing all research study in services (Pinhanez and Kontogiorgis 2008). This book represents a first attempt in that direction that will require further efforts and collaboration across disciplines. Appendix 1 actually opens up reflection on future research on design for services by starting a conversation with a selection of key researchers and professionals of the field of services. Finally, Appendix 2 presents a selection of tools as introduced in the case studies.

Before introducing the case studies that will feed into the map of design for services, we are going to address two key questions that will help us position and motivate this new field of studies: Why is it necessary to introduce a new subdiscipline in design? and How has design approached the realm of services so far?

As a response to these questions in the next chapters we will briefly consider the role and recognition of services and of design in the current economy and, following a similar path to service marketing in its original development, we will refer design to the IHIP (Intangibility, Heterogeneity, Inseparability and Perishability) framework,2 looking at how design developed alternative strategies in dealing with service characteristics to traditional design fields and service related disciplines.

Why Design for Services?

It is widely acknowledged that in recent decades the developed economies have moved to what is called a ‘service economy’, an economy highly dependent on the service industry. In 2007, services represented 69.2 per cent of total employment and 71.6 per cent of the gross value added generated by EU273 (Eurostat 2009).4 This means that services in their different forms and characteristics have developed a fundamental role for the growth and sustainability of innovation and competitiveness. This role has been fully recognised of late with a flourishing of innovation studies and policy debates and programmes specifically aimed at deepening the understanding and at supporting the development of the service sector at different levels. As a consequence the European Council called for the launch of a European plan for innovation (PRO INNO Europe) that could include and generate new understandings of innovation in general and of service innovation in particular.

Some of the key changes in these late policies have been a growing attention for the role of design and creativity as well as for user-centred approaches to innovation. PRO INNO Europe, the focal point of innovation policy analysis and development throughout Europe, dedicated a series of studies within this platform specifically to ‘design and user-centred innovation’ and to ‘design as a tool for innovation’.5 Initial studies at EU levels are suggesting the need for a more integrated and coherent measurement of design impact and design policies; recognition is growing on the role of design for innovation and on the importance to integrate design strategies at higher executive levels as well as to engage users on an early basis as co-designers (Bitard and Basset 2008).

The Community Innovation Survey (CIS), the most comprehensive European-wide approach to measure innovation based on surveys, has been gradually improved to better capture and report service innovation processes. The Oslo Manual (OECD/Eurostat 2005), on which the CIS surveys are based, has been updated since 2005 to include, besides product and process innovations, marketing and organisational innovation, and now considers non-R&D (research and development) sources of innovation as strategic for the development of service industries. A first attempt to produce a common measurement for service industry performance at a national level has resulted in the Service Sector Innovation Index (SSII). Different initiatives on the national level emerged out of this framework. For example, in the UK, the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA) has coordinated the development of a new Innovation Index (http://www.innovationindex.org.uk) in response to the Innovation Nation White Paper by the Department of Industries and Universities (DIUS 2008), which called for a more accurate measure of innovation in the UK’s increasingly important services sectors, creative industries and in the delivery of public services.

The need for a new Innovation Index emerged based on investigations into UK innovation practices, that revealed a gap between what ‘traditional innovation’ performance metrics – focused on scientific and technological innovation – were measuring and how ‘hidden innovation’ (NESTA 2006, 2007) was not being captured through them. At the same time it was being recognised that hidden innovation was one of the keys to success for the UK economy. Studies suggested the level of complexity involved in innovation, ill represented by linear models of innovation, the importance of incremental changes, and the role of diffusion. Moreover, further attention was to be given to the adoption and exploitation of technologies, organisational innovation and innovation in services (including public services and non-commercial settings). This example from the UK shows how our understanding of innovation needs to go beyond the traditional ‘hard’ dimensions of technologies and physical matter. Instead, we need to include the ‘soft’ dimensions that are directly related to people, people skills and organisations (Tether and Howells 2007).

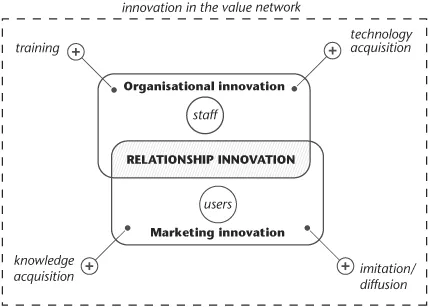

In synthesis, service innovation is ‘more likely to be linked to disembodied, non-technological innovative processes, organisational arrangements and markets’ (Howells 2007: 11). The main sources of innovation in service industries are employees and customers (Miles 2001) and new ideas are often generated through the interaction with users (user-driven innovation) and through the application of tacit knowledge or training rather than through explicit R&D activities (ALMEGA 2008). A dedicated study on service innovation by Tekes (2007), the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation,6 confirmed how customers have replaced the role of competitors as main source for innovation and how ‘customer services’ is the main area of service improvement (instead of ‘product–service performance’ in the manufacturing sector). Given the interactive nature of services, customer services and in general ‘delivery (or relationship) innovation’ (Gallouj 2002) have been looked at as the most characteristic form of innovation of services; however this practice is still poorly captured and understood. Other successful transformations into service companies often concern their organisational and financial models, moving from improving processes to the reformulation of their value networks and business models (Tekes 2007).

Service innovation is a complex interdisciplinary effort (Figure 1.2). Even if the role of design within this process is still not clear, it is starting to gain some visibility. Tekes for example suggests how design for services can apply design methods to develop a new offering or improved experiences by bringing ‘many intangible elements together into a cohesive customer experience’ (2007: 18).

Figure 1.2 A representation of the main areas of and sources for service innovation

THE TRANSFORMATIONAL POTENTIAL OF SERVICES

Among service innovation studies, special attention is being paid to the role services have in supporting the development of a knowledge-based economy; moreover services are often associated with the desired shift from a traditional resource-exploiting manufacturing-based society to a more sustainable one.

Knowledge-intensive Services (KIS)7 have been identified as an indicator for the overall ‘knowledge intensity’ of an economy representing a significant source for the development and exchange of new knowledge. These special kinds of services are now considered as connected to the overall wealth and innovation capability of a nation. As a subset of KIS, Knowledge-intensive Business Services (KIBS) have attracted significant attention. KIBS are services8 that ‘provide knowledge-intensive inputs to the business processes of other organisations’ (Miles 2005: 39) to help solving problems that go beyond their core business. Their growth is associated mainly with the increase in outsourcing and the need for acquisition of specialised knowledge, related to, among others, technology advancement, environmental regulations, social concerns, markets and cultures.

Services have been traditionally looked at as a possible alternative to the manufacturing driven model of consumption based on ownership and disposal. The concept of the Product Service System (PSS) developed out of the engineering and environmental management literature as an area of investigation to balance the need for competitiveness and environmental concerns. A PSS ‘consists of a mix of tangible products and i...